Report Overview

In this second edition of the Long Haul Low-Cost Series, we explore why there’s a real opportunity for low-cost airlines to foray into long-haul operations profitably. Our analysis includes the financial performance of low-cost airlines in the U.S. that have recently started operations over the Atlantic. We also include an analysis of whether the low-cost advantage of LCCs is big enough to overcome legacy airlines’ advantage as they operate a multi-cabin configuration on their aircraft. Does the cost advantage offset the premium cabin advantage that legacy airlines have?

What You'll Learn From This Report

- Analysis of JetBlue’s flights over the Atlantic

- Can premium cabin revenues offset LCC’s low-cost advantage?

- Markets that long-haul low-cost businesses can target

- Global Opportunities and Impact on Network Carriers

Executive Summary

In our second report of the Long Haul Low-Cost series, we present a different perspective on the feasibility of the long haul low-cost business model. While the difficulties faced in this model are widely documented, and we have covered them in detail in the first report of this series, we will showcase the potential opportunities for the long-haul, low-cost business model. We will analyze trends and technological innovations in the industry and use our estimation models to support our findings.

The post-pandemic surge in travel demand, the evolving preferences of younger generations, and the rise of the global middle class have transformed the landscape of long-haul, low-cost travel from unfeasible to profitable. Innovative aircraft technology, featuring more fuel-efficient planes with longer ranges, has also boosted the confidence of low-cost airlines to venture into long-haul operations.

Skift Research conducted a comprehensive analysis of successful low-cost carriers in the United States, building multiple models to estimate the feasibility and price competitiveness for long-haul operations when paired with an efficient aircraft and multiple cabin class configurations.

Our report thoroughly investigates and identifies lucrative opportunities for Low-Cost Carriers (LCCs) in the busiest long-haul routes and the overall long-haul market. The study concludes with a set of key insights that airline executives at LCCs and legacy carriers must pay attention to in order to stay ahead of the curve and remain competitive in the long-haul market.

Introduction

Over the past few decades, Low-Cost Carriers (LCCs) have significantly transformed the global short- and medium-haul sectors. They have successfully disrupted the short-haul market, gaining market share from legacy carriers. However, it remains a contentious issue whether they can replicate the same level of success in the long-haul market.

In the first report of the Long Haul Low-Cost series, we extensively discussed the challenges of the long-haul low-cost business model and why most tried airlines have failed. However, things are changing with the availability of newer and more fuel-efficient aircraft offering longer ranges, the growth of the global middle class, and the changing travel preferences of the younger generation.

In this report, we will analyse the post-pandemic landscape and its potential to offer airlines an opportunity to devise the correct strategy for penetrating the long-haul market. We also examine the capability of low-cost carriers (LCCs) to succeed in this challenging arena. We believe that LCCs can potentially disrupt the long-haul market and reach a global customer base of 150 million travellers if they focus on the right cabin, fleet, and network strategy.

To assess the viability of the global opportunity for long-haul low-cost business, we will delve into the financials of JetBlue, a major low-cost carrier in the United States, which recently launched a long-haul operation in 2021. The airline has chosen the Airbus A321neo, a cutting-edge narrowbody aircraft known for its remarkable fuel efficiency and long-range capabilities, for its transatlantic operations.

Overall, this analysis will provide valuable insights into long-haul, low-cost business prospects and the feasibility of using narrowbody aircraft for transatlantic routes.

Can a new generation of LCCs and aircraft make long-haul routes profitable?

The evolving dynamics in the aviation industry create a favourable environment for low-cost airlines to expand their operations into long-haul routes while retaining their cost advantage. For instance, airlines such as JetBlue attempt to take full advantage by increasing their long-haul network and improving their connectivity.

Analysis of JetBlue’s trans-Atlantic routes

Historically, budget airlines have encountered significant difficulties in matching the quality and corporate services offered by full-service carriers. To establish a foothold in the market, low-cost airlines such as Southwest Airlines, Ryanair, and easyJet have focused on providing cost-effective short-haul flights for leisure. However, this strategy was not feasible for long-haul flights until JetBlue started its long-haul services over the Atlantic in 2021. By introducing its long-haul flight services, JetBlue has succeeded in breaking new ground in the budget airline industry. The airline offers a business-class product that competes with full-service airlines. It has chosen the fuel-efficient A321 aircraft for its transatlantic operations, offering superior economics for its low-cost operations. JetBlue success over the Atlantic makes it an excellent case study for our analysis of the viability of long-haul, low-cost airlines.

We thoroughly analysed JetBlue’s financial statements to gain insights into its revenues from long-haul flights. JetBlue is one of the few low-cost airlines offering flights between New York and London. It has since expanded to include Paris and Amsterdam. As the airline increased its capacity on transatlantic routes, its operating profit margins also increased.

JetBlue is capitalising on the strengths of established US network carriers and making great progress. With an improved aircraft configuration that includes a class-leading business cabin, a loyalty program, and direct connectivity to some of Europe’s best destinations from primary airports in New York and Boston, JetBlue is going full steam ahead.

JetBlue started its long-haul transatlantic operations in 2021 and performed better than the network carriers (American, Delta, and United) on its European flights. The airline’s efficient operations, including using the most efficient narrowbody aircraft (A321) and careful capacity planning, ensured profitable operations in 2022 and 2023 (until Q3). In 2022, JetBlue achieved an average quarterly profit margin (operating income of flight operations exclusive of sales, marketing, general and administrative expenses) of 25%, while the network carriers had a negative profit margin of -5 %.

In 2023, despite the network carriers experiencing a surge in leisure demand, their average quarterly profit (flight operations) on transatlantic flights amounted to only 3%. In contrast, JetBlue achieved an average quarterly profit (flight operations) of 39%. This demonstrates the success that low-cost carriers can achieve by combining efficient, low-cost operations with strategic network and fleet planning.

JetBlue’s success initially on the New York to London route paved the way for further expansion. The airline quickly added service to other major cities in Europe and is now targeting more leisure destinations in the U.K., such as Dublin and Edinburgh.

Should this worry United, Delta and American? And can other low-cost carriers take note of JetBlue’s success and replicate it on other international long-haul routes? To better understand these dynamics, Skift Research ran another flight cost analysis. This time we looked at the airline level, comparing U.S. carriers that flew transatlantic to understand the differences between low-cost and network operations on long-haul flights.

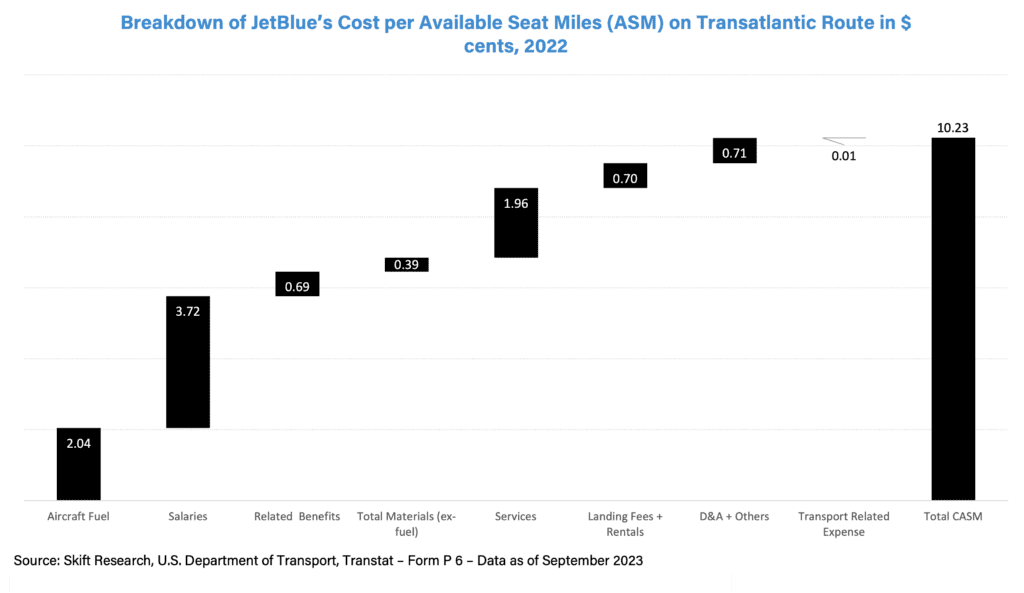

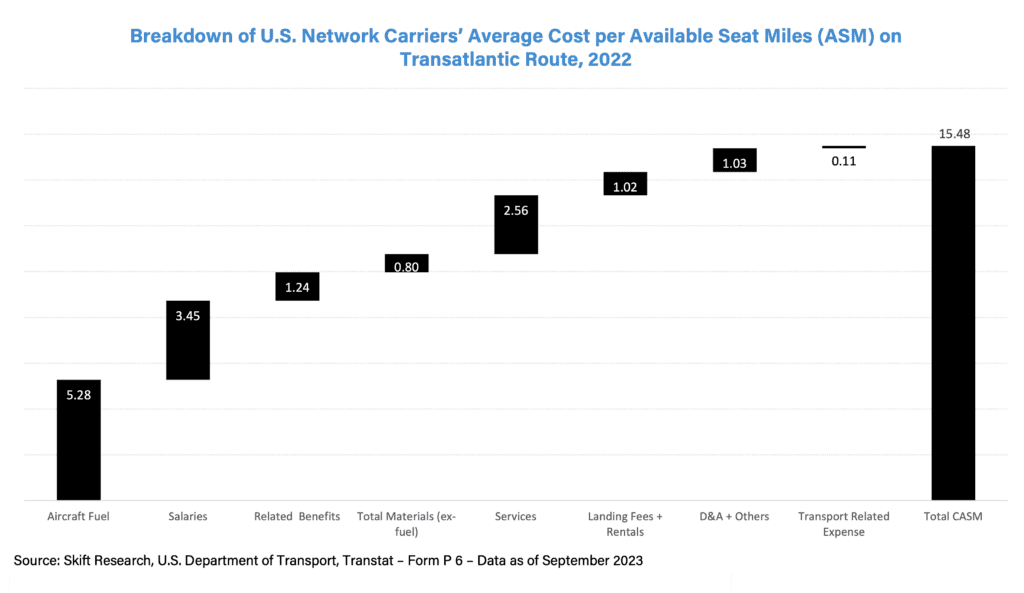

To conduct a thorough analysis, we evaluated the operational costs of JetBlue’s transatlantic flights in 2022 and compared them to those of the U.S. network carriers (American, United, and Delta). The primary operating cost categories included aircraft fuel, salaries, related benefits, total materials (ex-fuel), services, landing fees and rentals, depreciation, amortization and other transport-related expenses. The results were quite clear, due to its low-cost business model, JetBlue enjoys a significant cost advantage over its competitors.

In 2022, JetBlue’s stage length adjusted cost per available seat mile (CASM) on transatlantic flights was 10.1 cents. In comparison, the average CASM of network carriers is 16.9 cents (both are adjusted by a stage length of 3500 miles). The charts below provide a breakdown of the costs, which shows that JetBlue has a cost advantage over its network peers in all categories except salaries. JetBlue has a significant advantage over legacy carriers in terms of its fuel cost per available seat mile (CASM) due to its use of the most efficient narrowbody, the A321neo, on its transatlantic routes.

Although the salary cost per available seat mile for network carriers is slightly lower than JetBlue’s, this is likely due to the large-scale operations of the legacy carriers and because of JetBlue’s introduction of its signature ‘Mint’ business class cabins on its aircraft flying over the Atlantic, which generally require more experienced cabin crew members who are generally paid higher salaries.

Longer average stage lengths result in increased fuel burn, higher fuel expenses, and increased fees for widebody aircraft landing and premium onboard services offered by network carriers. These factors contribute to the higher CASM in all categories.

We have emphasised, analysed, and demonstrated the cost advantages of a typical low-cost carrier (LCC) over its network peers. This was again highlighted in the case of JetBlue, which boasts a significant cost advantage over its competitors. However, as previously discussed, this cost advantage diminishes as the flight length increases. Therefore, airlines must take additional measures to achieve success and profitability in long-haul operations. JetBlue’s success on its long-haul routes across the Atlantic is due to its superior cost advantage and changes to its aircraft, specifically adding business class cabins. This single change by JetBlue, which introduced premium class cabins on its aircraft, provides the airline with a point of differentiation that helped it run successful long-haul operations.

The question arises whether full-service carriers, leveraging their larger aircraft and multiple class configurations, can counterbalance the cost benefits offered by low-cost airlines. In other words, can they negate LCCs’ ability to attract customers by providing quality services and competitive pricing? Let’s find out.

Can premium cabin revenue offset LCC’s low-cost advantages?

Full-service airlines rely heavily on high-yield first and business-class passengers, who generate significant revenue for the airline. This revenue is then used to subsidise the cost of economy class seats, making them more affordable for passengers. This can be a significant challenge for the long-haul, low-cost airline business model.

In our earlier analysis, we compared the operating costs of a low-cost carrier (LCC) using a next-generation narrowbody aircraft with a legacy carrier using a modern widebody aircraft. The data showed that the LCC had an average operating expense of $32,520 per flight on a long-haul route, such as a transatlantic flight. In contrast, the legacy carrier had an average operating expense of $116,040 per flight on the same route.

However, it’s important to note that this analysis may not give a complete picture of the cost advantage on a per-seat basis, as it doesn’t factor in the potential subsidy that premium passengers can offer to legacy carriers. To address this, let’s update the analysis to consider the ability of full-service carriers to offer multiple cabin classes.

Skift Research ran two scenarios, one with the LCC running a single configuration economy cabin (as they do on short-haul) and one where the LCC offers a two-class cabin with an economy and a business class (taking a cue from JetBlue’s success)

Scenario A: The LCC flys an all-economy configuration

In this scenario, a low-cost carrier in an all-economy configuration earns $57,788 on a one-way ticket flying narrowbody aircraft (Airbus 321neo) between JFK and LHR with a capacity of 150 seats and a passenger load factor of 80%.

In contrast, a legacy carrier earns $161,622 on the same route operating a widebody aircraft (Boeing 777) with a capacity of 276 seats and a passenger load factor of 80% in a two-class configuration (Economy and Premium). Using current market fares, we assumed premium cabin fares are four times the economy class fares.

The legacy carrier, owing to the larger capacity of the aircraft, can generate 64% more revenue than the LCC. On this operation, the legacy carrier can generate an operating margin of 28%, while the LCC can generate an operating margin of 44%. However, the LCC can leverage its cost advantage and run the flight on breakeven fares ($271 per economy seat) – while the legacy can only drop its economy fares to $329 per seat to stay operationally breakeven – giving the LCCs a price advantage of 21% against its network peers.

One can argue if taking current market fares is the right way to approach this analysis. Therefore, we did an alternative analysis, where the core driver for the analysis was a 10% operational profit for both the legacy carrier and the LCC. We found that the LCC has a price advantage of 17% over the legacy carrier on its economy class fares.

Scenario B: LCC flys a two-cabin configuration

In a two-class cabin configuration, the LCC improves its revenue. It generates a total of $92,461 on a one-way ticket flying narrowbody aircraft (Airbus 321neo) between JFK and LHR with a capacity of 150 seats and a passenger load factor of 80%.

On the other hand, the legacy made $161,622 operating a widebody aircraft (Boeing 777) with a capacity of 276 seats and a passenger load factor of 80% in a two-class configuration (Economy and Premium). Using current market fares, we assumed premium cabin fares are four times the economy class fares.

On a total revenue basis, while the legacy carrier generated 43% more revenue than the LCC, the LCC improved its operating margins from 44% to 65% in a two-class configuration compared to an all-economy cabin. This demonstrates that LCCs can succeed and become profitable on long-haul operations when using a superior aircraft product. A two-cabin configuration offers superior operating margins for the LCC, improving the cost advantage significantly. The LCC can offer its business and economy fares 58% lower than the legacy carrier’s operating breakeven fares.

Alternatively, if we take a 10% operating margin as the basis for the analysis instead of current market fares, the results are consistent with our original analysis. LCCs still retain their price competitive advantage over legacy carriers and can offer economy and premium cabin tickets at 47% lower cost than the legacy carrier.

Based on the findings of this analysis, it is evident that a generic low-cost carrier (LCC), by its business model, not only possesses a considerable edge to provide competitive fares, even on long haul routes – which are considerably less expensive than those offered by its legacy counterparts but when paired with a great aircraft product this advantage could escalate to the extent that network carriers will find exceedingly difficult to replicate. All of this while remaining committed to the business model of low-cost carriers, which operate the same class and type of aircraft without adding the complexity of widebodies.

What does this development mean for the airline industry?

Routes and Markets that new aircraft and business models could target

The potential for LCCs to disrupt the long-haul market is enormous, and we should not underestimate the value of this opportunity. We believe that by leveraging their competitive advantages, LCCs can provide affordable and convenient travel options for passengers while also achieving sustainable growth in the long run.

To this end, we identified the top 10 busiest long-haul routes (between 2,000 to 4,000 miles) globally that can become potential markets for LCCs that venture into long-haul operations.

Four of the ten busiest long-haul routes are domestic (all in North America), and the rest are international city pairs. The busiest city pair is London and New York, with nearly 32,000 flights between them in 2023. Also in the top 10 are two city pairs (Bangkok and Seoul, Bangkok and Tokyo) from Asia and two Middle Eastern hubs (Dubai and Doha) connecting with London

The busiest routes in the world have formidable leisure and business demand, and traffic flows between them, making them relatively safer bets for low-cost carriers to start long-haul operations.

With the advantage of having slots at New York’s John F. Kennedy Airport, JetBlue banked on this opportunity when it started its first flights from New York to London in 2021.

Potential Market for Long Haul Low Cost

Skift Research built a proprietary model to estimate the impact of long-haul, low-cost service on the top 10 busiest long-haul routes worldwide. We estimate that low-cost carriers operating on the top 10 long-haul routes have the potential to serve over 13.7 million and nearly 150 million passengers on long-haul routes globally.

We started with the top ten busiest global routes, but analyzing the potential market for LCCs is not straightforward as these routes are from different regions. First, we need to understand the market penetration of LCCs in different regions.

We also subdivided these regions by flight length. For instance, in the domestic U.S. market, LCCs have a 53% share on short-haul routes, while in the Middle East, the penetration of LCCs in the short-haul market is just 22%.

The difference in the market penetration is also visible on long-haul routes. In Asia Pacific, for instance, LCCs have a market share of 33%, whereas, in the Middle East, LCCs only have a 10% market share on long-haul routes.

We used these regional market share figures as the drivers for scenario analysis. Our scenario considerations are based on LCC’s current market share on short, medium and long-haul routes in those regions.

| Scenario | Consideration |

|---|---|

| Low | Long Haul |

| Medium | Medium Haul |

| High | Short Haul |

So, a High scenario for a Middle East route (Dubai to London) will mean the market share of LCCs will be the same as LCCs’ current market share on short-haul routes in the Middle East.

Since the penetration of low-cost airlines differs invariably in all regions, we added a scenario-based analysis to our study. We looked at three scenarios – Low, Medium and High – where we estimated the analysis share under low, medium and high growth scenarios. Our final estimated number for the top 10 long-haul routes is a weighted average number based on probabilities for the three different scenarios.

| Row Labels | Region | Share of LCC seats in 2023 | Low Growth Scenario – Share of LCCs | Medium Growth Scenario – Share of LCCs | High Growth Scenario – Share of LCCs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bangkok-Seoul | Asia | 46% | 33% | 35% | 37% |

| Bangkok-Tokyo | Asia | 27% | 33% | 35% | 37% |

| Dubai-London | Middle East | 0 | 10% | 19% | 22% |

| Doha-London | Middle East | 0 | 10% | 19% | 22% |

| Los Angeles-New York | North America – Domestic | 38% | 43% | 45% | 53% |

| New York-San Francisco | North America – Domestic | 36% | 43% | 45% | 53% |

| Toronto-Vancouver | North America – Domestic | 46% | 43% | 45% | 53% |

| Honolulu/Oahu-Los Angeles | North America – Domestic | 35% | 43% | 45% | 53% |

| London-New York | US – Europe | 9% | 21% | 33% | 36% |

| New York-Paris | US – Europe | 16% | 21% | 33% | 36% |

Low Scenario

Our low scenario estimates the long haul market in the top 10 routes will expand by 24%, with the total long haul market served by low-cost carriers increasing to 12 million airline seats, up from 9 million airline seats.

Our low scenario is also the most realistic growth scenario for two major two routes on the lucrative transatlantic market (New York to London and New York to Paris) that currently have a small share of capacity by low-cost carriers (9% on the New York to London route and 16% on the New York to Paris route). We believe that LCCs on transatlantic routes have the potential to improve from this point to as high as 21%. This is, however, contingent on securing slots at major airports, which can be very costly, and having a fleet strategy that supports this venture.

Similarly, our estimation for realistic growth of LCC in the Middle East long haul market also falls under a low growth scenario. The Middle East long haul market is entirely dominated by legacy carriers and might see a smaller presence by LCCs in the long haul as LCCs have continued to strengthen their presence in major Middle Eastern hubs. OAG reported that LCCs have improved their share from 17% in 2019 to 25% in 2022 at Dubai International Airport. LCCs had a 25% share in 2022 at the Abu Dhabi International Airport, up from 6.5% in 2019. Their improving presence in major hubs will be key in starting long-haul operations.

Medium Scenario

Our medium scenario estimates the long haul market in the top 10 routes will expand by 45%, with the total long haul market served by low-cost carriers increasing to 14 million airline seats, up from 9 million airline seats currently.

High Scenario

Our high scenario estimates the long haul market in the top 10 routes will expand by 63%, with the total long haul market served by low-cost carriers increasing to 16 million airline seats, up from 9 million airline seats. This scenario is also the most reasonable growth scenario for the North American domestic long haul market where major LCCs like Southwest, JetBlue, Alaska, Hawaiian and Spirit compete directly with U.S. Network carriers and have the potential to improve their collective share to up to 53% capturing the lion share of those markets.

Asia Pacific’s long-haul market is the only international long-haul market where LCCs enjoy a significant presence. Bangkok to Seoul route currently has a 46% share held by LCCs, and Bangkok to Tokyo has a 27% market share held by LCCs. Due to geography, this region has the highest number of LCCs operating on long-haul routes. While routes in other regions see a maximum of three LCCs operating and competing with legacy carriers, Asian long-haul routes have six LCCs on some routes competing head with legacy carriers. Our analysis expects the penetration of LCCs on these to be high, as high as 37% on all its long haul routes – with Bangkok to Seoul being the only exception as it already has a very high concentration of LCCs on that route. This region also has the highest number of widebodies operated by LCCs for long haul operations.

Impact on network carriers

Low-cost carriers (LCCs) have successfully captured a significant share of the short-haul market, but legacy carriers have maintained their dominance on long-haul routes until now. Legacy carriers control almost 75% of the total capacity in the top busiest global routes. However, this might change as we expect more low-cost carriers to venture into long-haul routes and existing LCCs to increase their capacity on these routes. Legacy carriers that are most likely to be impacted by the long-haul low-cost development by region are:

- U.S. – Europe: United Airlines, Air France, British Airways, Delta Air Lines and American Airlines

- Middle East – Europe: Emirates, Etihad and Qatar Airways

- North America (Domestic): American, Delta Air Lines, Air Canada and United Airlines

- Asia Pacific: Air Japan, All Nippon Airways (ANA), Thai Airways, Korean Air

We estimate that while legacy carriers will continue to dominate routes to and from the Middle East, Europe, and over the Atlantic, markets in Asia and the U.S. domestic market will see a shift towards low-cost carriers operating and dominating those markets.

Legacy carriers earn a significant portion of their revenue from long and ultra-long flights. Therefore, legacy airline executives must be cautious of the competition from low-cost carriers (LCCs) in this segment. They should counter the growth of LCCs by leveraging their strong presence in these markets, larger and more diverse fleets, and the ability to offer premium services such as first and business class.

Additionally, legacy carriers should invest heavily in building their network of international partnerships to offer a broader range of destinations and convenient connecting flights to their customers. Legacy carriers have adapted and innovated to remain competitive, but this could be their most formidable challenge since the pandemic.

What is the Global Opportunity for Long Haul?

We previously analyzed the top 10 long haul routes, but the total long haul market has over 2400 unique routes between cities worldwide. This makes it challenging to determine the potential size of the total market.

One way to estimate the potential size of the total long-haul market in terms of airline seat capacity would be to use the findings on the top 10 long-haul routes and extrapolate those results to the rest of the routes. Since the top 10 routes represent only 9% of the total long-haul market, we can multiply the result by a factor of 11 to estimate the total market size, assuming linear growth across all routes.

Assuming a low scenario growth for all long-haul routes, we conservatively estimate a total global market size with a capacity of around 130 million airline seats.

On the other hand, if we assume a high growth scenario for all routes, we estimate a global market size of nearly 175 million airline seats. In perspective, this is equivalent to the combined airline seat capacity of Alaska Airlines, JetBlue, Frontier, Allegiant, and Hawaiian Airlines in 2023 – some of the biggest low-cost carriers in the United States.

Conclusion

The viability of low-cost carriers (LCCs) over long-haul routes, as opposed to short and medium-haul, has been an area of concern. However, the modern-day low-cost business model and changes in the global macro-environment have made long-haul low-cost operations more achievable.

JetBlue’s success in the transatlantic market in 2021 and subsequent expansion in Europe serve as a blueprint for LCCs looking to venture into long haul operations. JetBlue’s fleet strategy, which included investing in modern fuel-efficient narrowbody aircraft and updating its aircraft cabins, along with leveraging primary airport slots in New York, London, and Paris, made all the difference for the airline, enabling it to operate successful and profitable flights between the US East Coast and Europe.

Skift Research has developed a comprehensive cost and capacity model confirming low-cost airlines’ potential to operate long haul flights successfully. The model takes into account various growth scenarios across different regions. While airport slots and bilateral agreements between governments are critical factors determining the expansion of low-cost carriers into long-haul operations, our model concludes that if executed correctly, LCCs can challenge the dominance of traditional airlines on long-haul routes. We suggest that LCC executives take a leaf out of our long haul, low-cost strategy book, centring around a combination of cost competitiveness, advanced fleet strategy, and cabin configuration, alongside an effective loyalty program and securing slots in at major business hubs.

Our analysis indicates that the long-haul haul, low-cost airline market could offer between 130 million and 175 million seats. LCCs (low-cost carriers) that adopt an effective long-haul strategy can potentially become significant players in this market, as demonstrated in regions such as Asia Pacific. Although the growth may be slower, many LCCs will likely venture into lucrative markets such as Transatlantic and Middle East – Europe to establish themselves in the long haul market. For a legacy carrier executive, long haul low cost is bad news. As demonstrated by LCCs in the short and medium-haul, LCC can be a formidable force to compete with. To defend their most lucrative markets from the incoming competition, legacy carrier executives should secure and expand their slots at major airports, innovate their loyalty programs to include benefits outside of earning miles, integrate technology on their older systems, especially distribution channels and reinvent cabin configurations.