Report Overview

The hotel owner landscape is broad and diverse. They run the gamut from small business men and women to major NYSE-listed real estate investment trusts. There are many different decisions each hotel owner needs to make, whether to affiliate with a franchise or not, what kind of property and customer to target, and how they will market, distribute, and operate their properties.

This report will primarily focus on what we believe to be the most important decision a U.S. hotel owner has to make: whether to affiliate their property with a franchise brand or to distribute and market the hotel independently. We will look at the relative performance of brands vs. independent hotels during COVID, their costs, and their different distribution strategies. We also take a look at the hard vs. soft brand debate and how some independent owners are responding.

We also have a special focus topic on the state of staffing in the hotel industry today and close this report with five key takeaways for hoteliers.

What You'll Learn From This Report

- An overview of the different roles and players that make up the hospitality ‘stack’

- Branded vs. independent U.S. market share

- A deep dive into the branded hotel owner today including how brand standards are evolving

- A look into the distribution capabilities of independent vs. branded hotels including channel mixes, how loyalty evolved during the pandemic, and cost structure.

- A deep dive into the relative performance of different brands and independent properties during and after COVID-19 in the U.S.

Executives Interviewed

- Navroz Saju, Founder and Principal of HDG Hotels

- Noah Silverman, Marriott’s Global Development Officer for US & Canada

- Norm Leslie, President of National Hospitality Services

- Ray Martz, CFO of Pebblebrook Hotel Trust

The Hospitality ‘Stack’

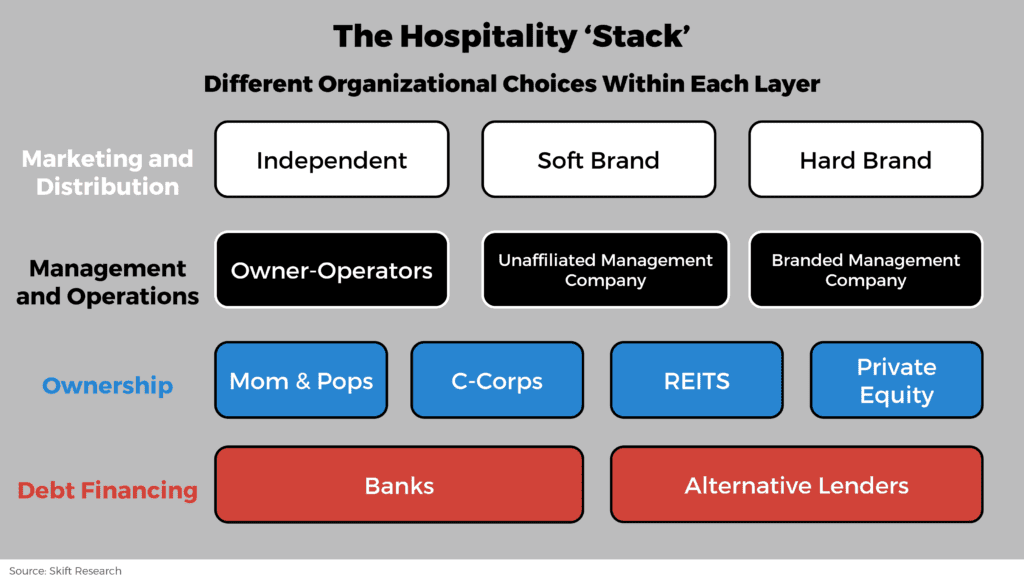

It’s become popular in the tech world to speak about stacks, a reference to how many different pieces of software often need to be built on top of one another to create a finished end-product. There is also, of course, a capital stack in finance which similarly refers to the way different providers of capital layer on top of each other.

We can apply this concept to hospitality to build a stack that represents the four primary functions of the industry and the types of players that exist within each layer.

Capital Structure:

The bottom two layers decide how any given hotel project will be financed, a simplified version of the capital stack.

- Debt Financing: The hotel business is fundamentally grounded in a real asset, and hotel investors, like all real estate investors, tend to use leverage. The primary providers of debt to the hotel space are banks, and their willingness to lend greatly affects whether the industry expands or contracts. Increasingly, more alternative forms of financing outside the banking industry are popping up. These include loans from leasing companies, private debt funds, and non-traditional vendors.

- Hotel Owners: These are the equity investors in the hotel space and the key decision makers for how to arrange all of the different pieces of the stack. This is perhaps the most diverse layer of the hospitality industry. There are many small-and-medium enterprises that own a single hotel or a handful of properties. There are also investors with much deeper pockets, like large hotel corporations that choose to operate an ‘asset-heavy’ model, and private equity funds. Some of the largest single owners of hotel properties are hospitality real estate investment trusts (REITs). These entities raise money from the general public and trade on exchanges like a stock. By law they must focus on real estate investing and are limited in what kind of other businesses they can enter into (though many create legally distinct, but affiliated, subsidiaries to expand into non-real estate ventures).

Go-To-Market Structure:

The top two layers of the stack determine how any hotel will go-to-market. The Managerial layer informs what kind of product the hotel will be, while the distribution layer determines how the end-customer will hear about the property and make their decision to book.

- Management and Operations: Once you’ve put together the cash to buy or build a hotel, who will actually be running it once the first guest walks in the door? The decisions made here will determine what kind of hotel product this is and if it can be successful. Do you want to run a limited-service property with as few staff as possible or a full-service luxury operation with many, highly trained staff? Some owners choose to operate their own properties, as a natural extension of their investment in the space. This runs the gamut from a bed & breakfast — which is technically an owner/operator — to very sophisticated hotel corporations like Loews Hotels or Omni & resorts. However, many owners prefer to be strictly financial investors and outsource the day-to-day management to a professional company. There are independent management companies that are brand agnostic, and branded management companies that are affiliated with and specialize in running a property to a specific corporation’s franchise standards. This can be confusing because most of the major hotel franchisors also offer affiliated management companies that are vertically integrated with their parent, but we recommend thinking about these as two separate sub-divisions that happen to share the same name.

- Marketing and Distribution: This is the top-most piece of the hospitality stack and the layer most visible to consumers. Arguably the most important decision any hotel owner needs to make is whether to affiliate their property with a franchised brand or to market their property independently. This decision affects every other piece of the business: your distribution costs, your marketing reach, your operational flexibility, your availability of financing, and the cost of loans. Going with a brand offers a safety net and simplifies a lot of choices, but it also means sacrificing a lot of operational flexibility and distinctiveness. A relatively new innovation in the branded space is the emergence of looser soft-brand affiliations that attempt to compromise between the two sides of the spectrum.

At pretty much all points in the hospitality stack, owners can decide to mix and match providers and to combine across verticals. Some owners do it all, owning, operating, and branding their properties. Others go with a joint management and branding deal, while yet others choose to hire independent operators at a franchised flag.

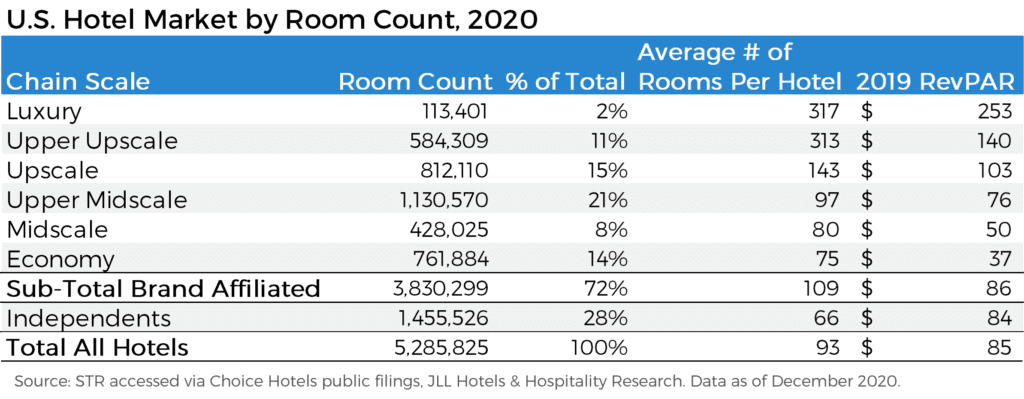

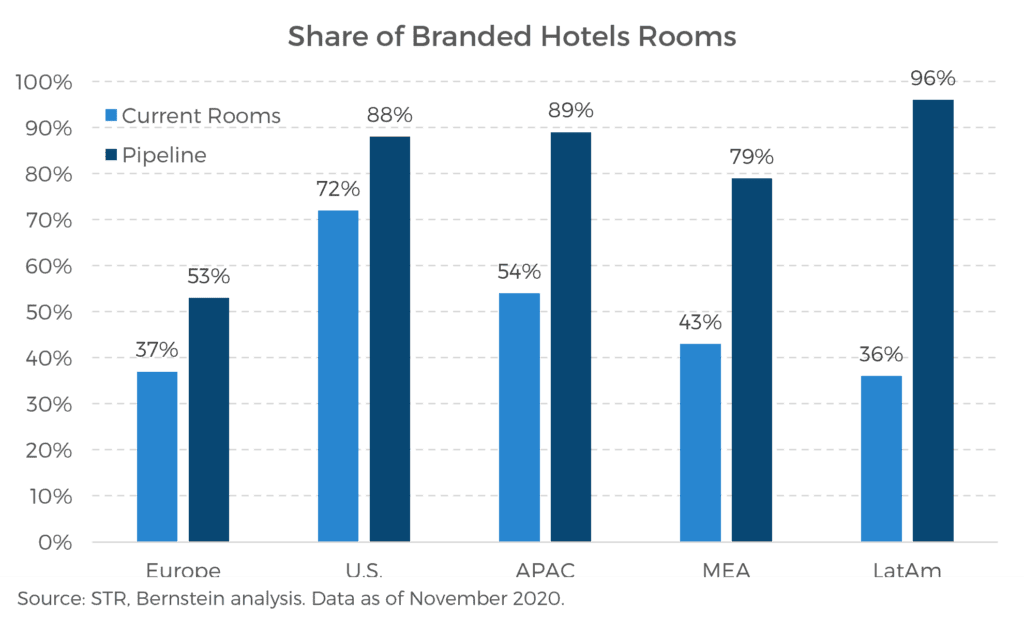

Currently, ~72% of hotel rooms in the U.S. are branded, according to data from STR. The majority are the upper midscale segment, though other sizable chunks are upscale or economy.

That is dramatically different from other parts of the world where branded hotels make up ~35-55% of rooms. In Europe, the independent market is the majority of properties and brands make up just 37% of rooms. The U.S. actually used to be quite similar, but has transformed over the last 30 years. In 1990, just 46% of U.S. rooms were affiliated with a brand, more in line with the global average vs. 72% today.

This report will primarily focus on what we believe to be the most important decision a hotel owner has to make: whether to affiliate their property with a franchise brand or to distribute and market the hotel independently. In the next two sections we will examine each type of hotel owner separately and evaluate how the independent vs. branded decision has impacted their performance during COVID, their prospects for recovery, and their financial standing.

The Branded Owner

Brand Support Helped During The Pandemic

The owner operating a branded hotel has had many advantages over the course of the pandemic.

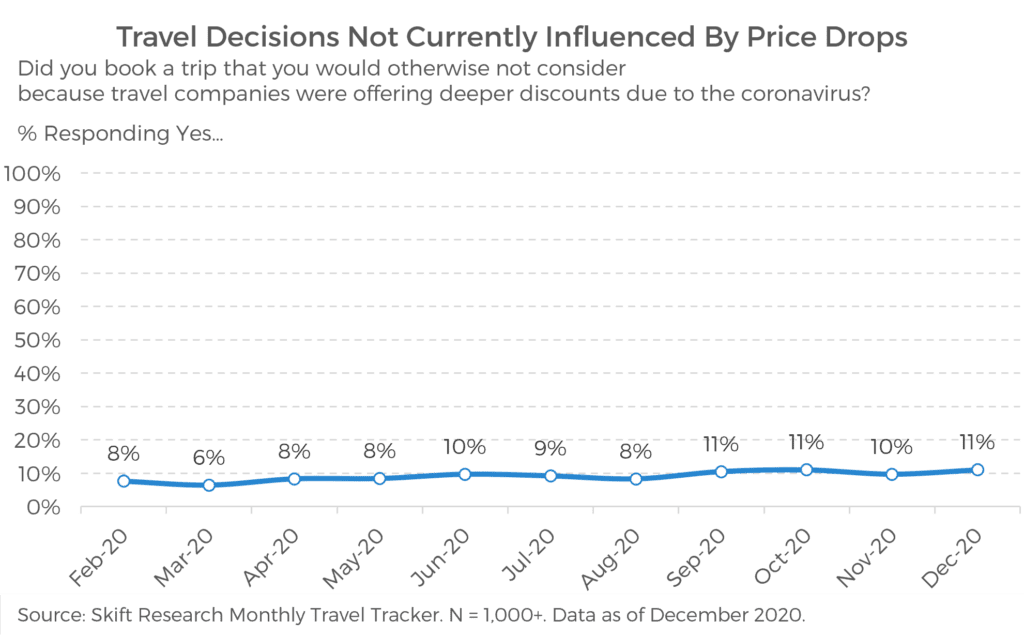

Our research has found that COVID-19 was fundamentally a crisis of trust and safety, not a financial crisis. Throughout the worst of the pandemic, less than one in ten Americans that we surveyed told us that they booked travel because of price discounts.

Rather than price being a blocker, the number one blocker to travel was concerns about health and safety. This meant that hotels needed first to design higher cleaning standards and then second, to convince guests to trust that they were capable of implementing them to a high standard. In both cases, brands have a large advantage over independents.

Due to their pure scale, the large hotel brands have more access to scientists and experts. They used this to create and launch very public hygiene standards for their properties, often in partnership with well-respected consumer household cleaning brands or public institutions. Hilton, for instance, consulted with the Mayo Clinic and Lysol in designing and launching its safety initiatives. The Four Seasons worked with Johns Hopkins University.

| Company | Initiative | Guidelines |

| Marriott | Marriott Global Cleanliness Council | Commitment to Clean |

| Hilton | Hilton CleanStay | New Standard of Cleanliness |

| Accor | ALLSAFE | The ALLSAFE Label Framework |

| IHG | IHG Clean Promise | IHG Way of Clean Enhancements |

| Hyatt | Global Care & Cleanliness Commitment | Global Cleanliness Accreditation |

| Four Seasons | Lead With Care | Global Program Guidance |

| Wyndham | Count On Us | Health & Safety Protocols |

| Choice Hotels | Commitment to Clean | Protocols and Products |

| Best Western | We Care Clean | Five Key Areas |

| Red Roof Inn | Red Roof RediClean | Protocols for Employees and Cleaning |

| Extended Stay America | STAY Confident | Stay Safe, Stay Healthy, Stay Comfortable |

| Radisson Hotel Group | Radisson Hotels Safety Protocol | Protocol Overview |

These collaborations all make for a great marketing coup, but the second piece of the puzzle is implementation.

Even if an independent hotelier followed all of the CDC’s health recommendations, they still needed to convince the traveling public that this was so. Unfortunately, cleaning standards were upheld with varying degrees of strictness during the pandemic and standards were constantly shifting. This undermined the traveling public’s trust in many independent properties and advantaged the brands. After all, their main selling point for a hotel brand is consistency and reliability. And consistency and reliability of cleaning is exactly what travelers demanded during the pandemic.

It was also nice to have the support of a multi-billion dollar corporation during the pandemic. These deep-pocketed organizations were able to work with franchisees in a number of ways to support their owners. This included advice about how to apply for emergency PPP loan aid, relaxation of brand standards, releases of cash reserves, delaying improvement plans, and centralized market research to develop a marketing strategy. And it is typically easier to secure bank loans if you are affiliated with a national brand. Noah Silverman, Marriott’s Global Development Officer for US & Canada, says, “I think we have been as open and as receptive and as engaged with them through this period as perhaps at any time that I can remember in my time with the company and I’m coming up on a quarter of a century

“On the one hand, this was a very unprecedented, very unique challenge,” says Navroz Saju, Founder and Principal of HDG Hotels, a hotel development and management company based in Ocala, Florida with 1,800 branded rooms. “But on the other hand in terms of the help available and in terms of the industry uniting to survive this, [the response] was [also] unprecedented.”

Between A Rock and A Hard Place

Over the July 4th weekend, U.S. revenue per available room (RevPAR) was up 5.7% over 2019 levels, the first time the industry has been able to surpass pre-pandemic performance levels. With hotel revenues now fully recovered it is time to celebrate, right? Perhaps that is the case for hotel franchise and management companies, which both get paid as a percentage of the sales they are able to generate, but branded hotel owners shouldn’t break out the champagne yet. They need their properties to be cash flowing profits, a top-line recovery won’t cut it. Many survived by cutting expenses with the support of all stakeholders. But will they be able to maintain these reduced expenses for long enough to generate the profits needed to refill their cash coffers?

In the middle of the crisis, lenders understood the unique circumstances and were willing to negotiate forbearance agreements with their clients. Banks let hotel owners defer interest payments, push back principal payment dates, and loosened covenant requirements. “Most if not all hotel owners went through some sort of deferment program with their lender,” says Saju. Lenders were accommodating because, after all, if the bank foreclosed on a property, they would find themselves in the unenviable position of needing to run a hotel in the middle of a pandemic.

But loans that seem likely to go bad must be reserved against – the banks are required to stake cash against the possibility that they will lose the capital they lent out, cash that could otherwise be earning a return. Not to mention that in the wake of the 2008 housing crisis, regulators pay very close attention to non-performing loans made by financial institutions.

This balance sheet drag and upcoming regulatory scrutiny means that the banks will not remain lenient with hotel owners for long. They will very soon be pushing for owners to make past due payments so that they can mark their hotel loans as re-performing or they will begin to foreclose on properties.

Similarly, the hotel brands stepped up to support their franchisees. Most relaxed brand standards, allowed owners to tap into cash reserves, deferred implementation of property improvement plans, and in some cases cut franchise and management fees. “We’ve tried to be as flexible as we can,” says Silverman.

“The brands gave a lot in terms of helping, more so than I’ve ever seen before,” says Saju, “but the bottom line is your hotel [has been] running occupancy in the low teens to zero for several months and the hotel is a high capital dollar business.”

As travelers return to the road in greater numbers than anyone could have expected, they may be disappointed to find their old reliable brands are not quite as reliable as they used to be.

These two supports from the banks and flags have propped up hotel owners but are likely to be withdrawn soon as the strength of the travel market in the U.S. becomes clear. Ironically for many hoteliers that survived the pandemic, it might be the recovery that does them in.

Brand standards are slowly being reimplemented and property improvement plans are being drawn up. Additionally, the banks are likely to begin asking for their dues in earnest.

This one-two punch will trap many hotel branded owners between a rock and a hard place. The brands will be making demands on their operating costs and the banks on their financing costs. All at the same time that revenue has only just returned – in some cases not even – and cash reserves have been entirely spent. And additional borrowing is likely not an option because most pre-existing loans are in deferment. “Access to capital is a huge challenge,” Saju tells us.

As Norman Leslie, President of National Hospitality Services, a hotel management company and owner with more than 3,600 branded rooms in 17 states, puts it, “Everybody had a stay of execution over the last 18 months. [… But now] as revenue returns, if a property is really severely under-managed, it’s going to really be drastically exposed.”

We think this will finally trigger a major shake-up within the hotel ownership space with survivors finding new paths to profitability alongside many that need to sell themselves or close up shop.

The Battle for Breakfast

There is a war raging beneath the noses of most travelers, the battle for breakfast. This fight has become emblematic of the broader struggle over which brand standards need to be returned and which can be abandoned.

Prior to the pandemic, many branded hotels in America offered a breakfast service of some sort; even limited-service brands would typically provide a continental breakfast.

But when the pandemic hit, dining rooms were closed. Firstly, of course, it was a government mandate, but even as restrictions were lifted, breakfast service remained shuttered as a cost control measure.

Breakfast can be an expensive proposition. Even the more limited continental or buffet services still can require several attendants and cooks, on top of food costs. A modest breakfast service can run at $3-5 per occupied room, according to Leslie. That may not feel like much in dollar terms, but bear in mind that U.S. hotel RevPAR in May 2021 was ~$70, meaning that this cost can lead to 4-7%+ swing in margin terms. For a business or convention focused hotel that is driving below average RevPAR, the decision to resume breakfast could easily cost 10 points of unit margin or more.

Are these expenses really necessary? After all, in most locations guests will likely have local breakfast dining options nearby (with perhaps the exception of all-inclusive resorts). On the other hand, some guests really enjoy and expect to have on-premise breakfast options.

Hotel brands are divided on how urgently to restore breakfast service as a standard, if at all. Jim Alderman, CEO of Radisson Hotel Group Americas, speaking at the NYU hospitality conference in June 2021 said that his properties had seen a hit to their net promoter scores (NPS) due to halting breakfast. On the other hand, Geoff Ballotti, president and CEO of Wyndham Hotels and Resorts, agreed that too many costs have crept into some branded operations, especially at the select service level. Wyndham has decided to halt breakfast service at its economy brands like Days Inn and Super 8. “It [breakfast] wasn’t the number one driver at those brands” he said, “we’ll see how it goes… but permanently those breakfast costs have been removed.”

Forgive us if you are reading this report on an empty stomach – it’s not really about the food. “Breakfast has been the first thing that the brands have been wanting introduced back to our guests in a more robust way,” says Leslie. But he points out that many other lapsed standards are being mulled over as well, from housekeeping to happy hours.

In our mind, this battle for breakfast is just the starting point and emblematic of the broader conversation over how quickly brand standards should be re-implemented and even if certain standards need to be cut altogether.

Yet at the same time we understand the need for brands to mandate capital expenditure improvements. Hotels are some of the most used and abused real estate properties out there and consumer tastes are constantly shifting. Without continuous maintenance and renovation, brands lose their draw and reliability – defeating the whole purpose of flying a national flag in the first place.

Marriott’s Silverman says that, “I think we are very mindful of the circumstances in which our owners and franchisees find themselves even still… at the same time, we also want to make sure that we are delivering to our customers the products and services that they expect. It’s a delicate balancing act right now.”

Compromise and flexibility will be key here. The franchisors will need to make room for more property and location specific exceptions to their standards on an ongoing basis while still having the backbone to enforce protection of their brands.

Loyalty is the Key Opportunity for Branded Hotel Owners

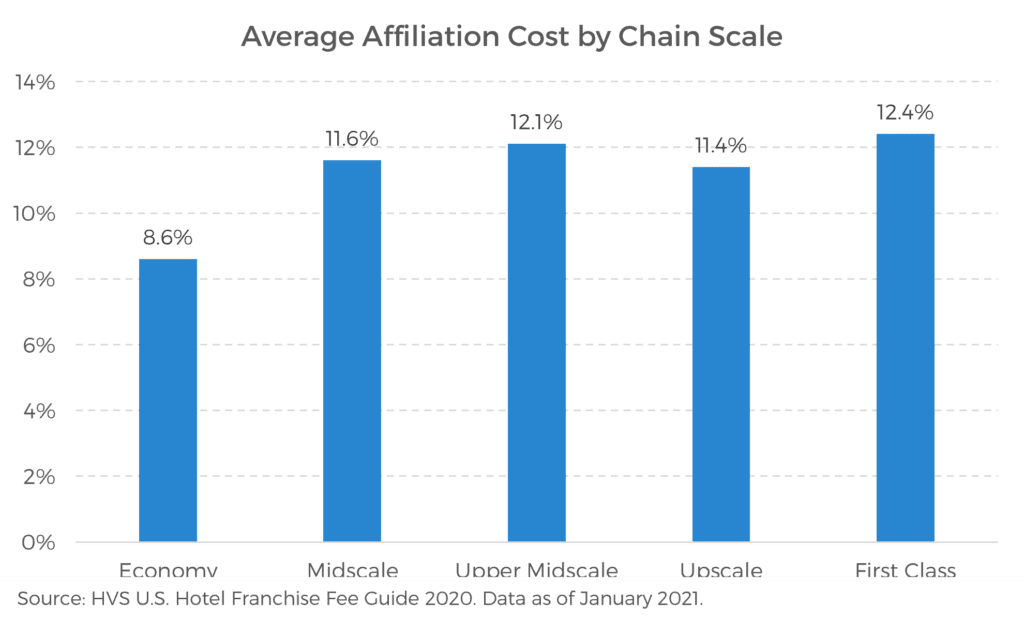

While brands are powerful drivers of demand, that intellectual property comes at a steep cost. Brands can charge ~9-13% in royalty fees, the industry median is 11.5%.

And that’s as a share of revenue, it doesn’t matter if you are turning a profit or not. On top of that you’ll also have to pay for software, training programs, and for enrollment in certain booster programs.

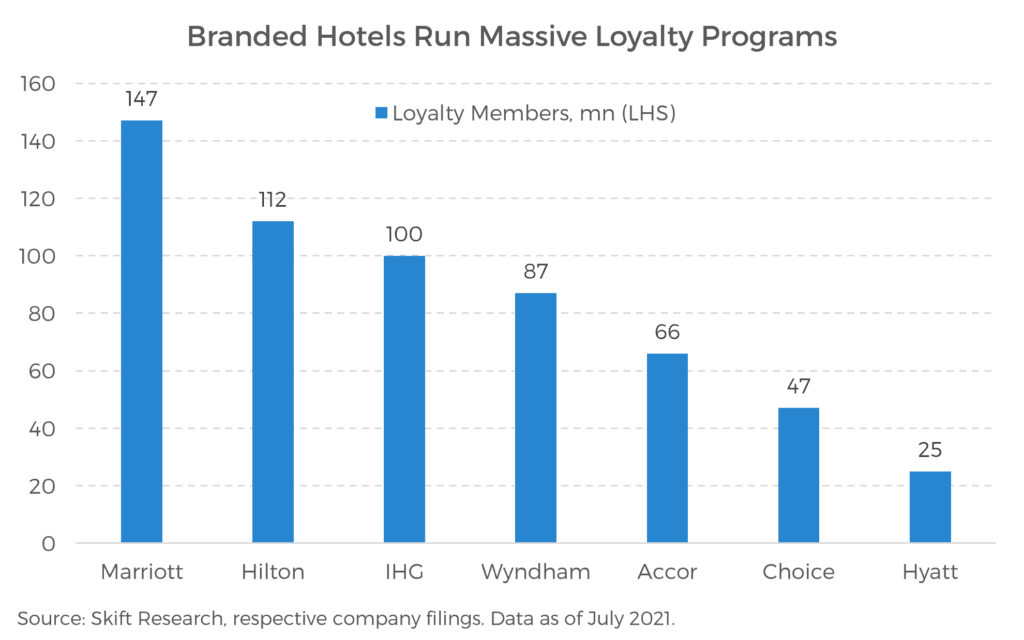

One of the most important tools that brands have in their belt is the loyalty program. All of the major brands boast of tens of millions of loyalty members, the largest three have even topped 100 million guests each.

“We like to deal with brands that have a strong loyalty program,” Saju confirms. Not only does he save on expensive OTA fees but he finds that loyalty customers, “tend to spend more at our hotels, pay a higher rate, [and] treat our staff better.”

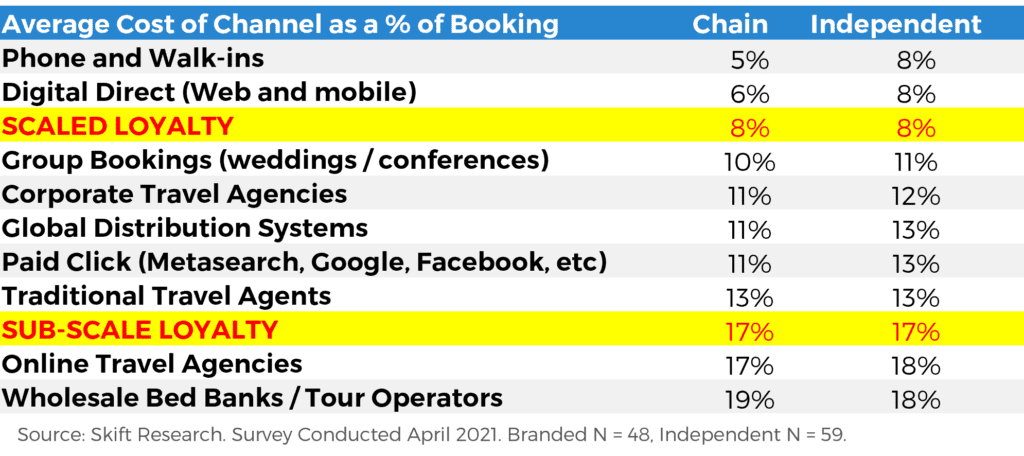

It’s not just a pure volume advantage, but loyalty programs can significantly improve Net RevPAR, and by extension boost EBITDA. We have found that highly scaled loyalty programs are one of the cheapest distribution channels available to hoteliers. Loyalty bookings, while not free, can be half as expensive as working with an online travel agency or other intermediary. Only walk-ins or direct bookings are cheaper.

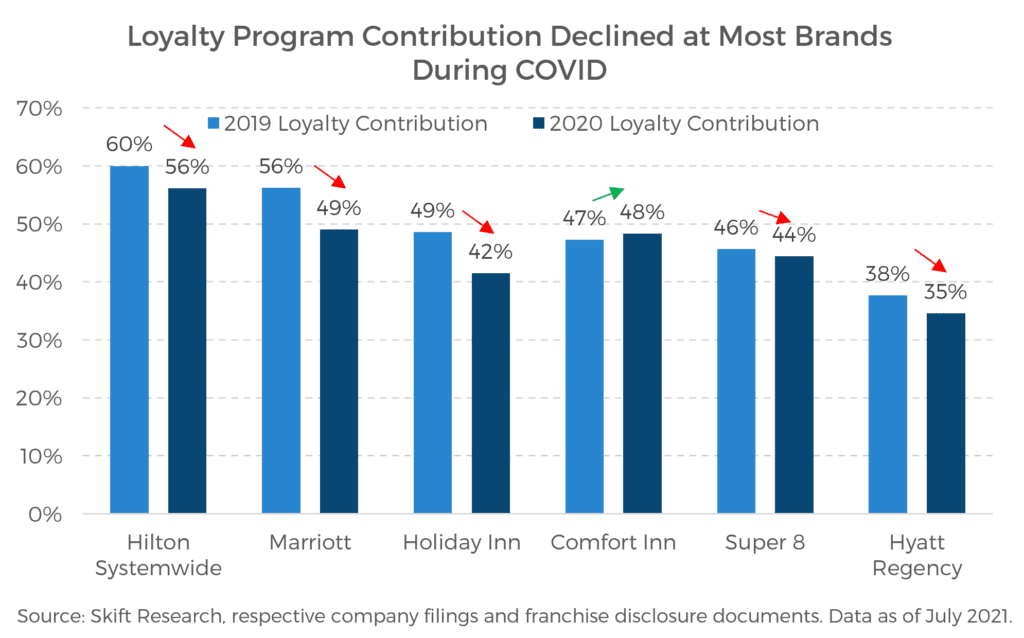

Interestingly though, loyalty has stumbled during the pandemic. When you would think that a large built-in network of customers would be most important, Skift Research found that most loyalty programs contributed less to their constituent properties than would have been expected pre-COVID.

We analyzed the franchise disclosure documents of six major hotel companies to understand how much revenue (or in some cases occupancy) loyalty programs were able to contribute to franchisee’s business during the pandemic. Hilton had systemwide loyalty contribution data for its Hilton Honors program. But for five other large franchisors in the U.S., we picked a single brand to analyze that we believed to be representative of dynamics within the loyalty program. The brands were: Marriott for Bonvoy, Holiday Inn for IHG Rewards, Comfort Inn for Choice Privilege, Super 8 for Wyndham Rewards, and Hyatt Regency for World of Hyatt.

We found that at five of the six hotel companies, loyalty contributions to revenue, or occupancy, actually declined during the pandemic. Only one brand, Comfort Inn by Choice Hotels saw loyalty contributions grow during the pandemic. Choice Privilege members made up 48% of room revenue at Choice hotels in 2020 during the pandemic, up one percentage point from 2019.

All other brands sampled saw loyalty contributions decline during the pandemic. Size of the program did little to offset any decline, and if anything actually had a negative impact. Marriott’s Bonvoy and Holiday Inn’s IHG Rewards saw the largest declines in loyalty contributions, falling seven percentage points during the pandemic. Those programs boast 147 million and 100 million members respectively.

We suspect that much of this decline can be explained by the stoppage of business travel, especially the high-end consultants and executives. We believe that the larger programs like Bonvoy over-indexed on these customers who earned their points via work and who have yet to return to the road. In contrast the Choice Privilege program likely skews towards economy business and leisure travelers who have fueled the first stage of the travel recovery.

This suggests that loyalty program contributions will return towards 2019 baseline levels as business travel returns. But the trend is worth monitoring closely in case old dynamics do not return.

And we should note that even if the contribution declined relative to pre-COVID, all major programs were still delivering 40%+ of the average branded hotel’s revenue or occupancy. That’s nothing to scoff at, and a very valuable book of business that independents could not access during the pandemic.

Branded Owners Need to Negotiate Flexibility With Partners

The travel recovery will require flexibility of owners, operators, and brands. We’ve written a lot about how hotel owners will need to negotiate individually with their lenders, management teams, and brands.

It is hard for us to give blanket advice. Each property is unique and will need to find a custom solution that works for its market. “Whenever we deal with the brand with particular issues dealing with our portfolio, it’s always, one-to-one,” says Saju of HDG. Maybe that is a conversion, a specific standard that can be cut, a new tech platform, or a loan restructuring. The solution looks different for everyone.

“I think the most common response for the brands right now,” explains Leslie “is as long as you’re a good member of the community, you’re performing, your guest service scores are there, you’re running a clean hotel… that if you had to get something done this year… to give you the [extra] time necessary.” He adds that, “they’re doing this on an individual basis.”

Norm Leslie makes perhaps the most important point about the current environment for workouts. It’s all about being a good corporate citizen. This is where long-term thinking and operating really shines. If you have been a good partner with your bank for many years now, it will be easier to work out a debt issue than if you have a history of late payments.

Brands are looking very closely at property-level guest satisfaction scores when determining how flexible they can be. If you have a well-trained staff and a cultivated core of loyal customers, your satisfaction scores have likely held-up, despite cutting standards. And as a result, brands will have breathing room to give you more leniency on reinstating expensive standards. “If you’re achieving certain metrics that maybe we continue to defer [a PIP],” Silverman explains.

The same courtesy will not be extended to properties that were already struggling or are showing signs of customer issues. Silverman tells us, “if you’re really falling down … then we may ask you to go deeper and, and do more so that we don’t lose the … the [brand] equity that we built up with our guests.” If regular maintenance has been done in a timely manner, PIP deadlines will be less urgent then for properties that were already due for an overhaul pre-COVID.

So, in many ways, the owners that will have the most flexibility to work through any teething issues, and that are most likely to be recovery winners, were pre-determined by their behaviors prior to the crisis. “If you weren’t operating a quality property before the pandemic, really that was probably the best litmus test to see if you […] should be afforded much [flexibility],” Lesie says. There may be some karma yet in this business.

The Independent Owner

Distribution is the Make or Break Challenge for Independents

The challenges faced by independent U.S. hotels ran the gamut from securing business loans, to finding staff, and procuring software and supplies. But perhaps the biggest challenge is finding distribution as an independent.

Digital performance advertising is effectively a giant auction and, for the last decade, online booking sites have gladly reached into their deep pockets to outbid solo properties. Plus independents rarely have the scale to mount effective loyalty programs or national advertising campaigns – the two tactics that hotel brands have found most effective at beating back the OTAs.

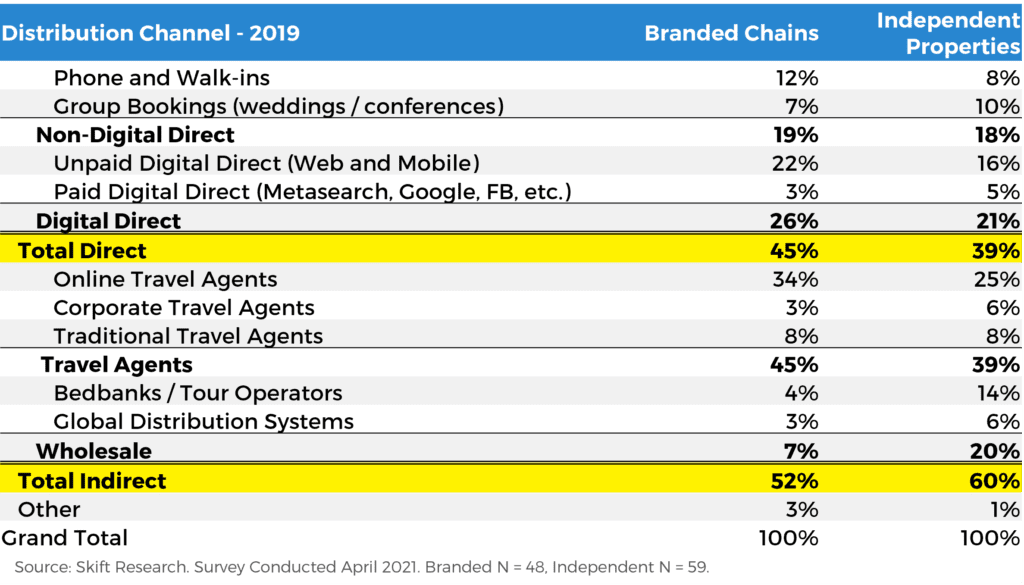

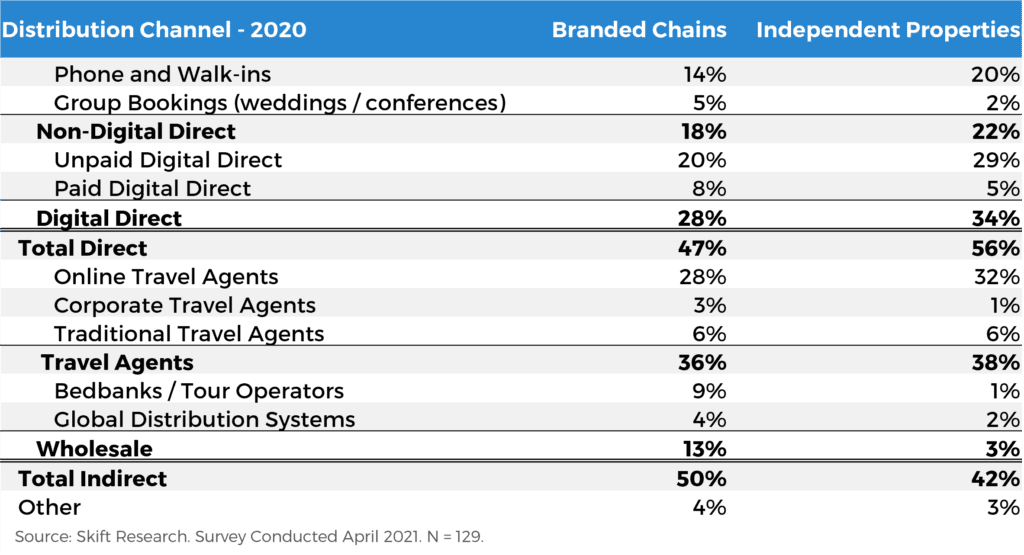

Our research confirms that independent properties rely more heavily on third parties for bookings. We found that in 2019, independent properties got a six-point smaller share of bookings from direct traffic sources than their branded peers – 39% vs. 45%. Direct bookings are often half as expensive as the same reservation coming via an OTA or other intermediary.

COVID has presented a new set of distribution challenges for independent hotels. In 2020, independent properties saw a much higher share of bookings from the direct channel than their branded peers, a reversal of the pre-pandemic trend.

And at first glance, this might seem to suggest that independents outperformed branded properties during the pandemic, but we think that this, counterintuitively, suggests that brands were in a stronger position.

During COVID-19, the fastest growing channel for independent hotels was phone and walk-ins. It grew eight points to be the third largest booking channel, representing a fifth of all independent pandemic sales. But let’s face it, phone reservations should not be a growth channel; millennials don’t like to pick up the phone. In this case, the rapid shift towards phone calls likely represents confusion amongst customers.

We think a possible explanation for this data is that customers knew and trusted the branded product well enough to be comfortable booking through websites or intermediaries without needing to call directly to confirm the information themselves.

We don’t see the sharp rise in phone and walk-in reservations as a pure strength, but rather a challenge since there is little doubt that the phone and walk-in channel will shrink in 2021.

All of these distribution challenges, both pre- and post-COVID, have had the net effect of squeezing out independent hoteliers. This crisis is likely to drive a wave of conversions into flagged properties. This is likely to happen within the branded space as well as underperforming flags are exchanged for more powerful ones.

To Convert or Not?

In light of these challenges, should independent hotel owners convert their properties to a national brand? While it can be quite costly, in times of crisis like this, it can be comforting to be partnered with a major corporation. The leaders of all of the major hotel brands are certainly convinced that conversions will drive their growth in the coming quarters.

“When I say conversions, it’s usually not just one word,” Marriot’s Silverman tells us, “it’s three strung together: conversions, conversions, conversions!”

Silverman says that, “in a downturn, owners of independent hotels see even more value in the [brand], I think of it kind of as reaching for that lifeline and security of the larger brand system and distribution platform, loyalty program, et cetera.”

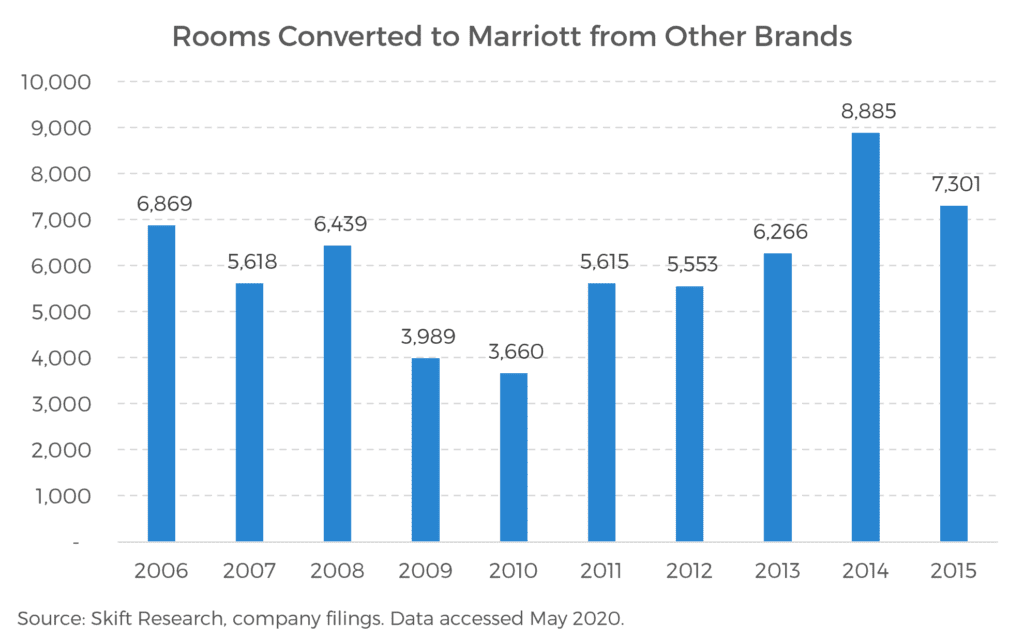

Him and his peers have reason to be optimistic. The 2008 financial crisis spurred a ‘flight to safety’ wave of conversions and they expect the same to happen again this time around.

Similar to what we suspect is happening today, conversions in the peak of the financial crisis were slow as well. As the late Arne Sorenson, then Marriott’s President and Chief Operating Officer, later its CEO, explained in 2010, “lenders have been hesitant to recognize losses and owners are hanging on for tomorrow.” But by 2011 and 2012, losses had to finally be recognized and more hotel properties came under new ownership. The Marriott development team targeted these properties for conversions and drove 26,000 rooms onto the company’s platform from competing brands in 2011 – 2014.

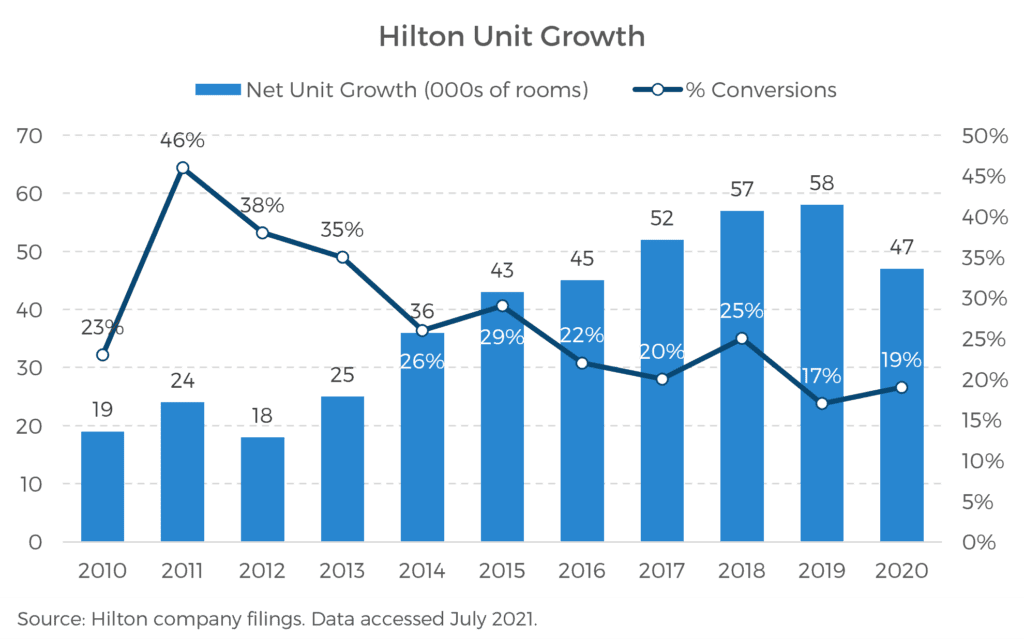

The story is the same at Hilton. In 2011, as the defaults from the financial crisis shook out, 46% of the company’s unit growth came from conversions. That was up 23 percentage points from the previous year. The following years remained hot for conversions which drove 35%+ of new unit growth at the brand in 2012 and 2013 as well. Finally, as the cycle normalized, Hilton returned to its baseline of ~20-25% of unit growth from conversions.

We think a similar story could play out this crisis. Defaults do not come as immediately as many initially expect, but eventually the dominoes begin to fall and that creates an opportunity for branded conversions. The simple fact remains that many independent hoteliers are struggling and looking for a branded lifeline to pull them to safety.

A common time for a hotel to switch flag or add a flag is when its ownership or management changes. When many hotel properties trade hands, we expect large financial firms like private equity shops and REITs to be buyers. These investors generally prefer to work with brands and we suspect that they will be eager to bid out new franchise and management contracts. “When we’re acquiring assets, we stick with the institutional players,” says Leslie, “what we refer to as investment grade franchises.”

Silverman says that, “some of [Marriott’s conversions] have come to us by workouts or bankruptcy proceedings or other transactions where the portfolio is a portfolio of hotels that may be trading. And for which a change of flag becomes a viable path for the new owner of that hotel. We’re monitoring all of those transactions as best we can.”

Plus, where else will the big brands find their unit growth from? Silverman explains that at Marriott, “the focus from a development perspective, not surprisingly turns immediately to conversions because we know that there will be fewer groups interested in developing new hotels, given occupancy levels.”

New construction of hotels has dried up in most major markets. COVID delays have slowed any projects that had already broken ground by early 2020. And new projects are slow to be given the green light – banks are still skittish about lending and gnarled supply chains have made many construction materials prohibitively expensive.

Large hotel companies are angling to take advantage of these scenarios with their designated ‘conversion’ brands – franchise agreements written and priced to accommodate existing hotels. Marriott’s two primary hard-flagged conversion brands are Delta Hotels and Four Points by Sheraton.

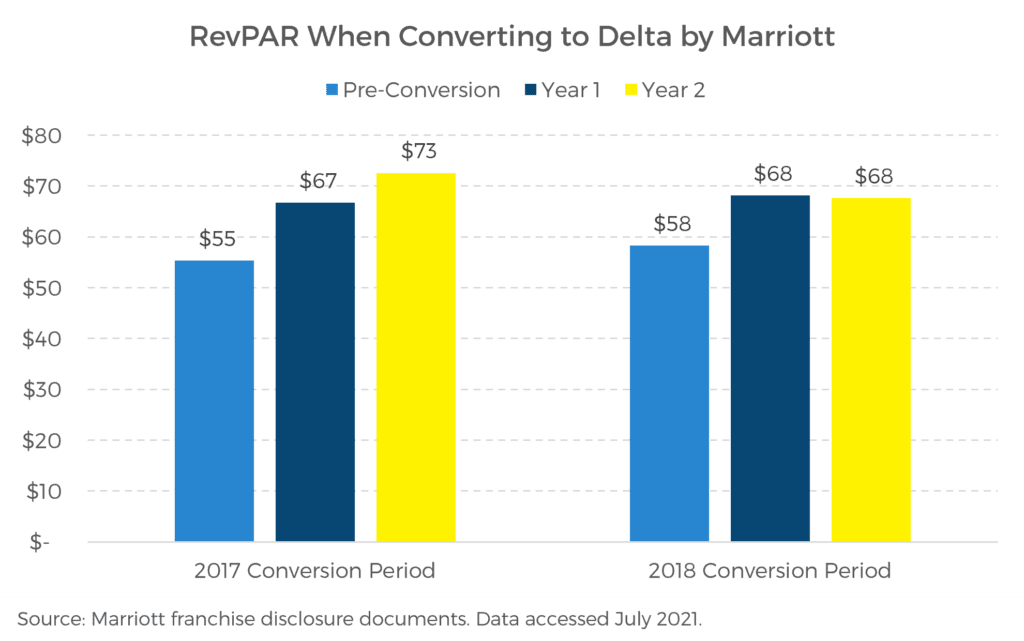

These conversions can sometimes be quite beneficial to hotel owners. “We do believe we can help a lot of independent hotels in particular with an affiliation with us,” says Silverman. Properties that were converted to Delta by Marriott in 2017 saw a 31% increase in RevPAR over the following two years. 2018 conversions grew RevPAR by 16% over the same period.

The RevPAR growth was driven by both pricing power increases and higher occupancy. So although the returns vary over time, there are clearly very substantial improvements that some owners can gain by converting to a brand.

Soft Brands as a Conversion Compromise

But many hoteliers don’t want to be tied down by strict brand standards and want their property’s individuality to speak for itself (and command a commensurate pricing premium). The middle ground between pure independence and a flag is a soft brand.

These are a relatively new innovation in the franchise space. Soft brands effectively offer a slimmed down version of the traditional franchise model. The branding will be light, often calling itself a ‘collection’ of hotels rather than a full-on brand.

Marriott launched its first soft brand, the Autograph Collection in 2010, which specifically targeted existing independent hoteliers. Since then, it has become one of Marriott’s fastest growing brands. The company has since gone on to launch two more soft brands, the Tribute Portfolio and the Luxury Collection. Each targets a different segment of owners and chain scales that may want to switch over independent ownership.

Silverman says that, “even before the pandemic, we were seeing a large percentage of growth among our full service brands coming from the soft brands. And I think that trend line has just continued in their pandemic.” He shared that he believes 2/3rds of growth in the full service space came from three brands, two of which were the soft offerings Autograph and Tribue. The third was Delta, which we discussed above.

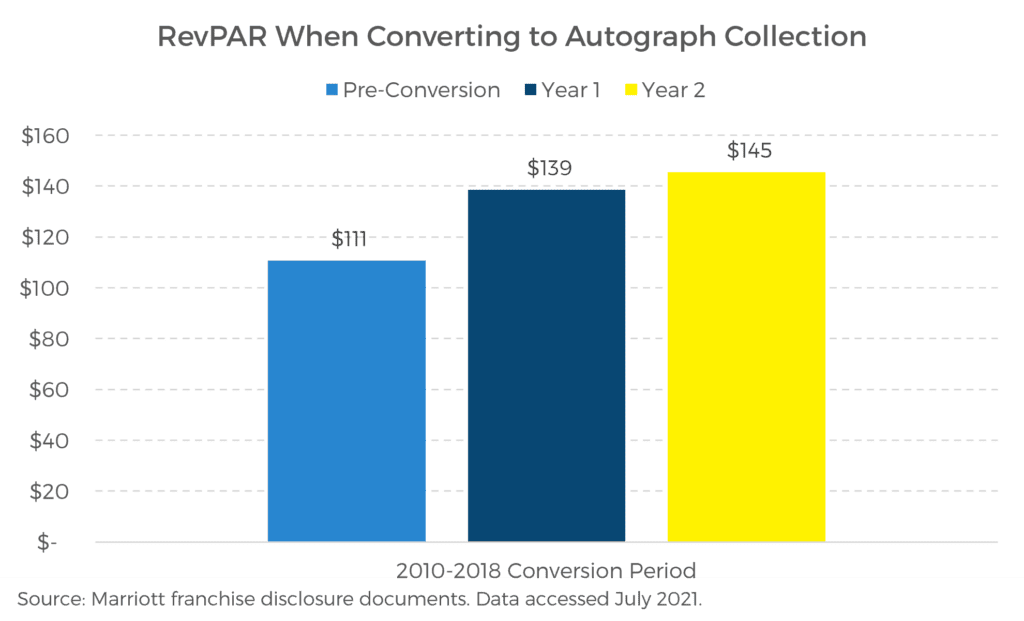

Franchise disclosure data shows that Autograph hotels see a 32% increase in RevPAR within two years of converting to the collection. This is similar to the performance of the Delta hard brand conversion boosts. And for the average Autograph, Bonvoy members contributed 49% to occupancy in 2019, so the loyalty distribution advantage is real.

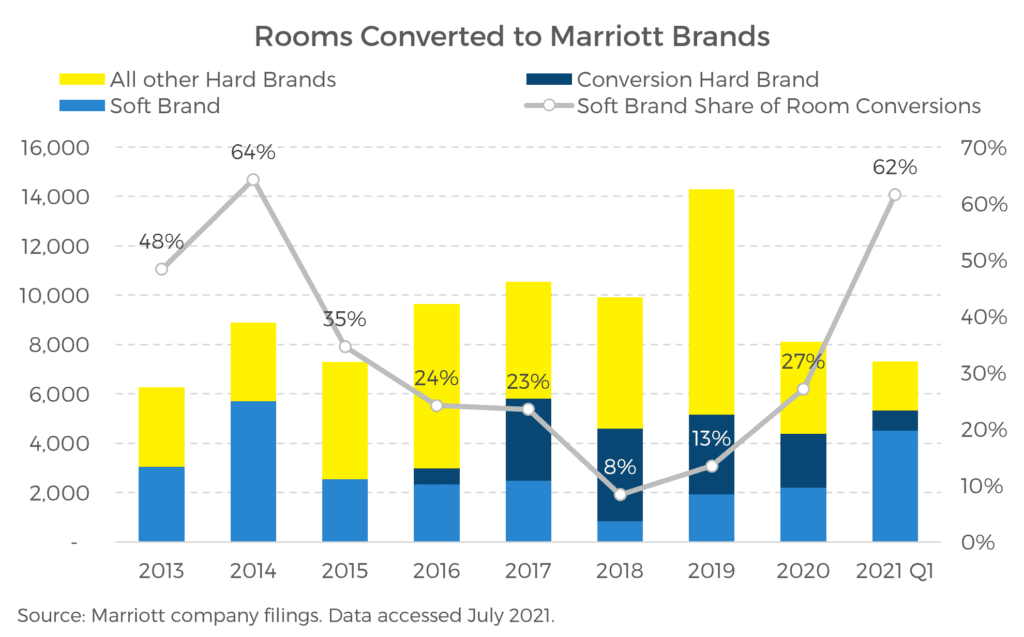

This compromise that offers a performance boost from conversion without the brand standards clearly has deep appeal to hoteliers, especially in the current distressed environment. Our analysis of Marriott’s data shows that soft brands rose to account for about a third of all rooms converted to Marriott during the pandemic in 2020, well above the rate seen for the last five years.

To date in 2021 soft brand conversions have exploded. Marriott signed ~4,500 new rooms within their three soft brand collections in Q1 2021, representing 62% of all conversions in the quarter. If that pace were to continue for the full year, Marriott would be on pace to convert more rooms to its soft brands in 2021 than it did over the last seven years combined.

While our analysis here has focused on Marriott, they are not alone in seeing success with soft brands. All of the major hotel companies also have one or several soft brands including the Curio Collection and Tapestry Collection from Hilton, the Ascend Collection from Choice, the Unbound Collection from Hyatt, and more.

Finding an Independent Path Forward

But what about true independents? They are still 28% of the market after all.

For those that truly want to maintain their independence, they will need to walk a third path that rethinks the independent model and builds on a boutique approach and long-tail tech platforms.

Times are tough, but being independent still has some advantages. We described many branded hoteliers as facing pressure on two fronts. But independents can escape from one half of that trap – the rising cost of brand standards, affiliation fees, and improvement plans.

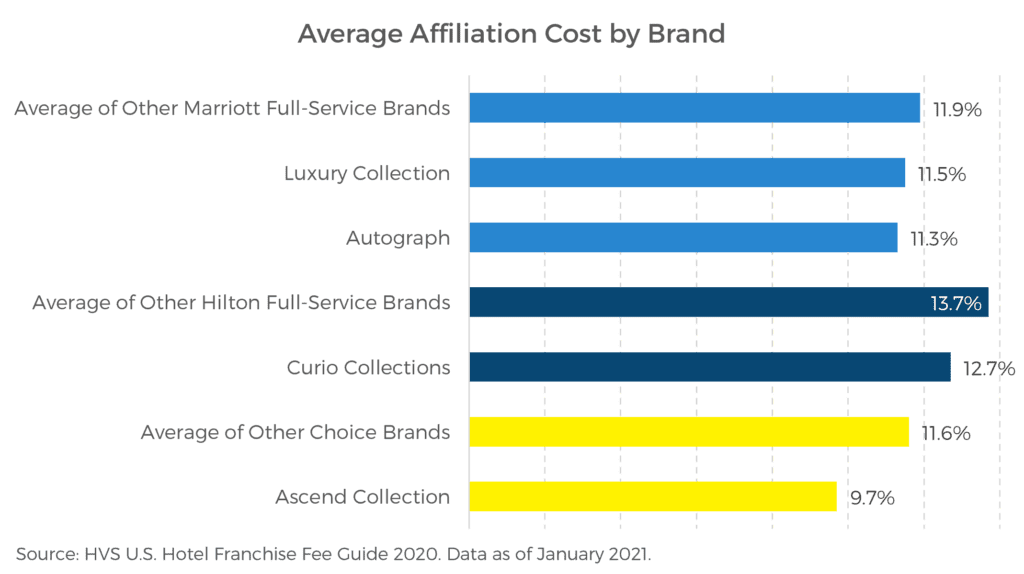

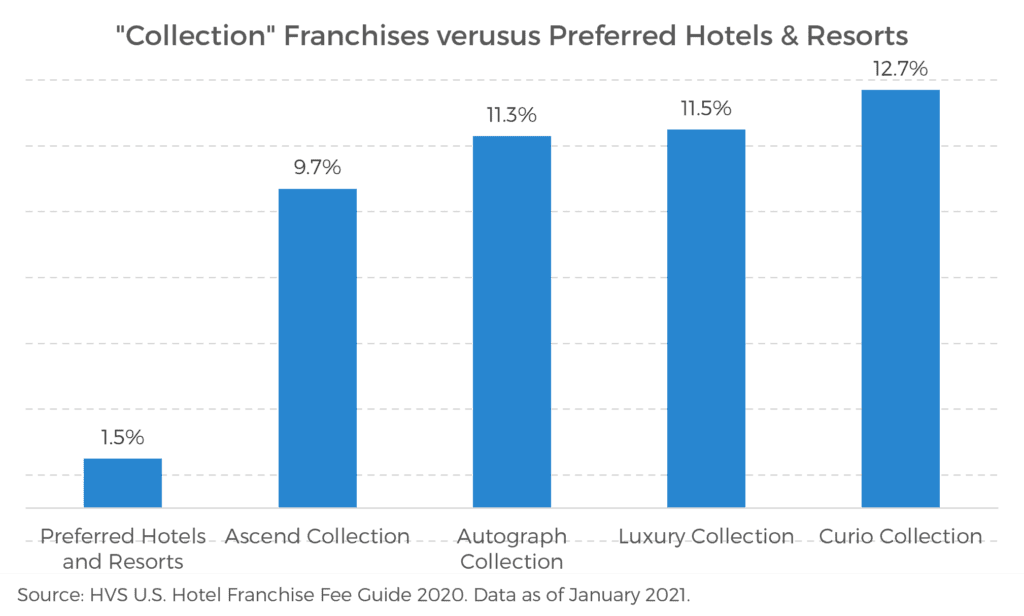

Even soft brands, the compromise option, while they can potentially boost RevPAR, are not cheap. In fact, according to an HVS study of affiliation fees, some major soft brands hardly offer a discount at all. The Autograph Collection by Marriott is just 60 basis points (0.6pp) cheaper than their hard brands. Hilton’s Curio Collection is only a 100 basis point (1pp) discount. Choice offers one of the best soft deal bargains, but even this only amounts to a 190 basis point discount, and the owner will still need to bake in a ~10% affiliation fee into perpetuity.

On an even bigger scale are the often major property improvement plans (PIPs), audits done by brands of each flagged property, that leads to large capital expenditures. Barry Sternlicht, of Starwood Capital, and former CEO of Starwood Hotels, claimed to spend $250 million on property improvement plans within his hotel portfolio without gaining any market share. “[Property improvement plans] are tied to the ego of the new brand,” he said. “It’s a tax on new owners of those hotels, and there’s no reason to spend the money.”

In this environment, we understand why many hoteliers balk at the prospects of such huge outlays that offer a questionable ROI. Still, the lack of l direct loyalty traffic is one of the biggest distribution challenges facing truly independent properties.

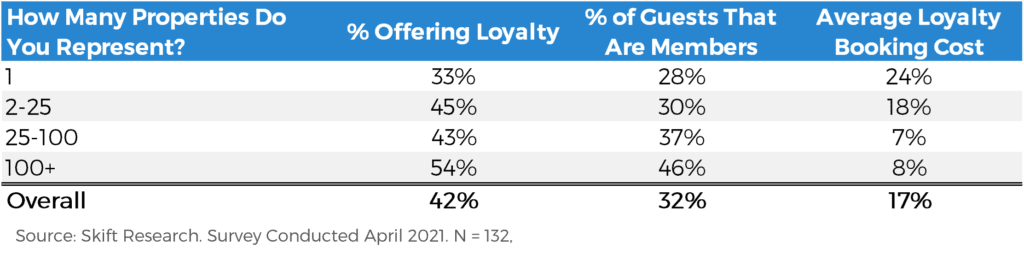

The challenge is that running a single-property loyalty program is almost prohibitively expensive. With a single property for instance, the cost of a loyalty booking can be as much as 24% of the booking — that’s the same as an OTA! The issue is that standalone hotels struggle to attract a wide network of repeat customers. As a result, only a third of independent hoteliers even attempt to offer loyalty.

But at a 100+ property chain, the average cost of a loyalty booking is just 8% – that is amongst the cheapest of all channels, almost on par with walk-ins. The breakeven point seems to be at ~25 properties, above which loyalty becomes a no-brainer, but below which it can be costly and cumbersome to maintain efficiently.

The solution in our view is for independent hoteliers to form loose affiliations based on shared technology platforms that can form new types of loyalty networks. An interesting example of this is Preferred Hotels & Resorts. Preferred is an independent soft brand of sorts. It has even fewer requirements than the soft collections of the major national franchisors, but does offer its own I Prefer loyalty network. It charges dramatically lower affiliation fees than any other soft brand on the market, just 1.5%. Leading Hotels of the World and Small Luxury Hotels of the World have similar formats.

Another company experimenting with new forms of independent affiliation networks is Pebblebrook Hotel Trust, one of the largest U.S. Lodging REITS. They have had great success owning upscale independent lifestyle brands and in November of 2020 launched a new hotel collection, called Curator Hotels and Resorts, aimed at building scaled infrastructure within their space.

Ray Martz, the CFO of Pebblebrook, explained to Skift that Curator is “a collection… it’s a non-brand brand.” Martz says that offering came in response to “seeing a lot of these really unique lifestyle hotels join a soft brand… and they didn’t necessarily want to do it, they felt they had to do it,” for all of the many reasons we have discussed above.

Curator plans to negotiate master service agreements with suppliers and technology companies to provide similar distribution services and cost management tools as can be offered by the big brands at a lower cost than independents would pay individually. For instance, Curator recently inked an agreement to provide it’s member hotels with discounted access to Sabre’s SynXis central reservation systems. This is the same central reservation technology used by many of the big brands.

But more than just getting access to the same tech as the big players at similar costs, Martz insists, it also is about encouraging innovation in tech systems. He cites the example of working with Toast, a popular point of sale system in the restaurant industry that has seen little uptake in the world of hospitality F&B. The challenge he explains is that, “when you’re with a brand, you’re stuck with the technology that the brand has,“ but Martz hopes that Curator will allow properties to think outside the traditional hotel tech box.

The Curator collection currently has 120 hotels signed up. “When we started Curator, we thought the market would be for potential Curating members to be about 500 hotels,” says Martz. “What we know now, six, nine months later, we think the market is probably double that size.”

Independents Offer the Best Opportunity to De-Commoditize

There is definitely a place for independents, but it is increasingly an upscale, lifestyle focused niche. The reason why is because these kinds of properties are distinctive enough to cut through the noise of the rest of the industry which is just building big boxes.

The OTAs annually spend more than $8 billion on marketing hotel rooms. In doing so they commoditize the hotel industry. Your property needs to fit into the box that Expedia or Booking have built for it so that it can easily fit into a Google search result or metasearch auction.

The only businesses with the pockets deep enough to compete against this spend on the online auctions are the large hotel brands. And when they do so, the OTAs only respond by raising their bids. This arms race in hotel digital advertising is a race to the bottom. And the ones who ultimately pay these billions of marketing dollars are the hotel owners (and the consumer to an extent). Just pick your poison, it can be OTA commissions or franchise affiliation fees.

In many markets and especially the lower chain scales, the bed has become a commodity that is only distinguished on price.

But by creating a hotel with a unique, individualized feel, savvy owners can de-commoditize their properties. This is best done in the independent space where properties can have the freedom to experiment with new design and technology. And independents can more authentically connect into the fabric of their local community. This short-circuits the price comparison mindset of many consumers. Uniqueness can help break the vicious spiral of digital performance advertising and thereby drive pricing power and cost-effective marketing distribution.

Martz of Pebblebrook says he has seen this effect first-hand. He believes that the distribution advantage of the big hotel brands is a “common misperception.” Pebblebrook saw little difference in occupancies between its independent and branded properties before the pandemic. (And data we received from JLL Hotels & Hospitality Research suggests this was still the case through the pandemic, see next section below). He explains that, “a key difference was, even though our independents needed to access OTAs more than the brands, the marketing sales costs were at half as much as what the brands charge us.”

In other words, the branded boost to direct bookings is real but it comes with it’s own cost and the risk of commodifying the property. Unwary hotel owners and operators may find themselves with high direct bookings traffic but locked into a high cost structure with minimal pricing power which has the potential to more than offset the first-party reservation advantage.

“At least from our experience, if you know what you’re doing, you can perform better and not have all that [branded] stuff,” Martz tells Skift. “And yeah, you may have to rely on the OTAs more and use Expedia and Booking.com, but overall, on the net-net basis of it, you’re leftover with more money at the end of the day, which is what it’s all about.”

Independents have the ability to de-commoditize their rooms. They can offer unique and local stays to a guest that is increasingly experiential and willing to pay a premium for these kinds of distinctive properties. This is the true potential of independent hotels, in our view.

But we also need to bear in mind that not every property can become an upper-upscale lifestyle boutique overnight. What about the midscale and economy level properties? There is a long tail of middle market independent hotel properties that may not be a good fit for Preferred Hotels or the Curator collection. It is these hotels that we believe will feel the brand pinch the hardest.

Who Performed Better During the Pandemic?

After all of this comparison between branded and independent hotels, one may be tempted to look for black and white answers about which performs better. This is ultimately an impossible question to answer definitively. Hotel performance is mostly determined on a case-by-case basis specific to each property’s location, market, and management. Nonetheless, there are some interesting insights to be gained by taking a look at broad performance differences between chain scales, across distribution types, and within brands.

Independents Held in Well Against Brands During COVID

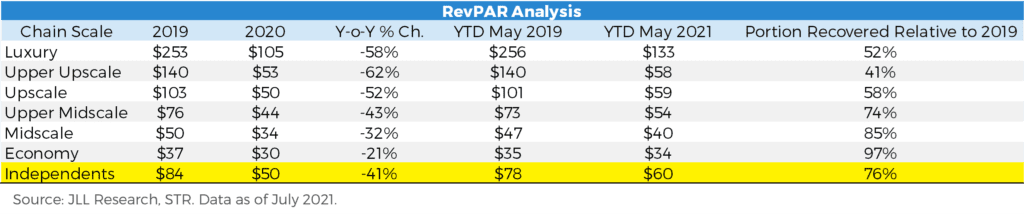

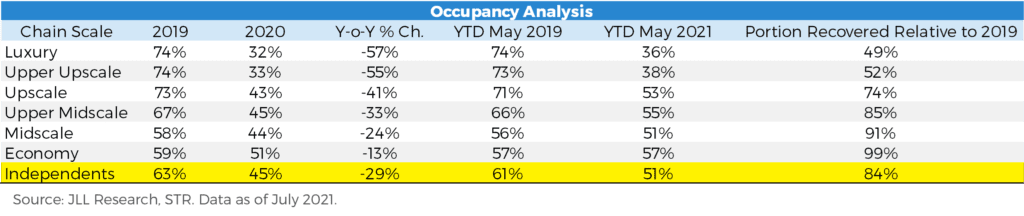

JLL Hotels & Hospitality Research, in an analysis performed for Skift, looked at hotel performance across branded chain scales and independent properties. They found that year-to-date through May 2021, RevPAR at independent properties was 76% recovered relative to 2019. For comparison, the average branded property’s RevPAR is only 68% recovered vs 2019. That means that the average independent has actually outperformed their branded peers during the crisis, though there is a lot of nuance to this conclusion.

JLL was able to slice this RevPAR performance by branded chain scales to provide us with the details of this performance. What this analysis reveals is that independents actually performed better than most branded hotels in the luxury, upper upscale, upscale, and upper midscale segments. On the other hand, the midscale and economy sectors well outperformed independents.

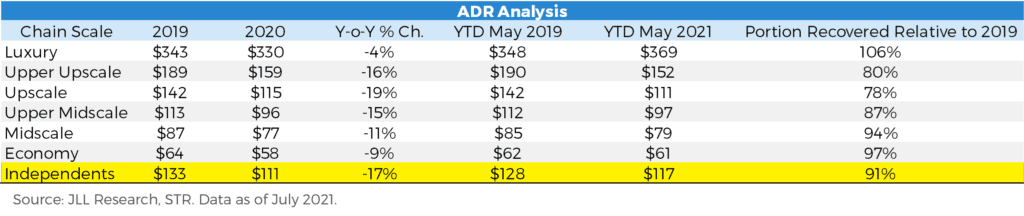

We can also decompose RevPAR into its two core drivers: rate and occupancy. Let’s take rate first.

Across the board, hotel industry pricing power has held in very strongly during COVID. This is one of the biggest silver linings of this crisis that makes it different from past recessions in 2008 or 2001. Independent ADR is currently at 91% of 2019 levels vs. 90% at branded hotels, for all intents and purposes identical. By chain scale it’s interesting to note that luxury hotels — one of the worst on a RevPAR basis — are doing the best on an ADR basis and has not just fully recovered but even taken a 6% pricing power lead over 2019.

With ADR fairly consistent, it should be no surprise that occupancy is the primary driver of diverging performance. Independent hotels are 84% recovered on occupancy vs. 75% for brands. But the branded chain scales have a wide spread. Luxury has had the hardest time filling rooms, 49% recovered, while economy brands have done the best job, 99% recovered.

Why did independents seem to have a slight edge over brands? It’s hard to say as there are many factors at play. For starters, independents tend to be smaller properties with 67 rooms on average vs. 109 rooms at the average branded hotel. This means it is easier for them to refill their occupancy rates at the same level of demand, and as discussed occupancy was the main reason for average independent outperformance.

It also could have to do with how the averages themselves are calculated. In terms of pre-COVID RevPAR, ADR, and property size, the average independent was most comparable to a branded Upper Midscale or Upscale property. Those two chain scales have recovered on a RevPAR basis 85% and 74%, respectively, that’s very similar to the independent space’s 84% recovery. So the appearance of independent outperformance could just be a statistical artifact of benchmarking them against non-comparable chain-scales, such as branded luxury, which dragged down the overall branded average.

Finally we note that this performance differential could easily reverse as the recovery continues. Luxury hotels have had the worst RevPAR performance year-to-date but they are the only segment with positive ADR growth. With demand coming back so quickly to the travel industry, and with consumer savings bolstered over the pandemic, we can envision a scenario where luxury occupancies quickly snap back and drive it to the top of the RevPAR charts.

Cross-Brand and Intra-Brand COVID Performance

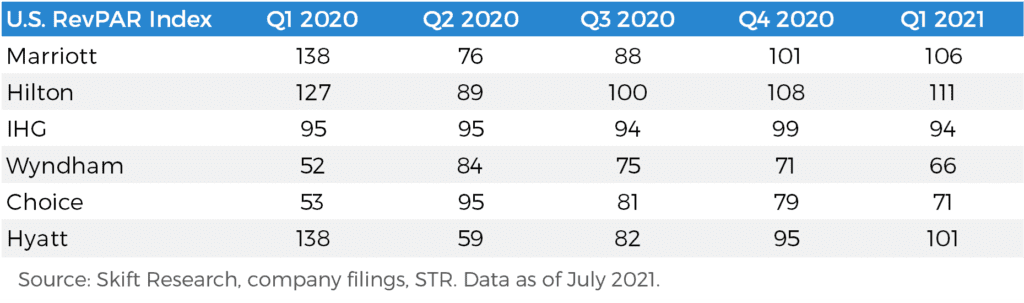

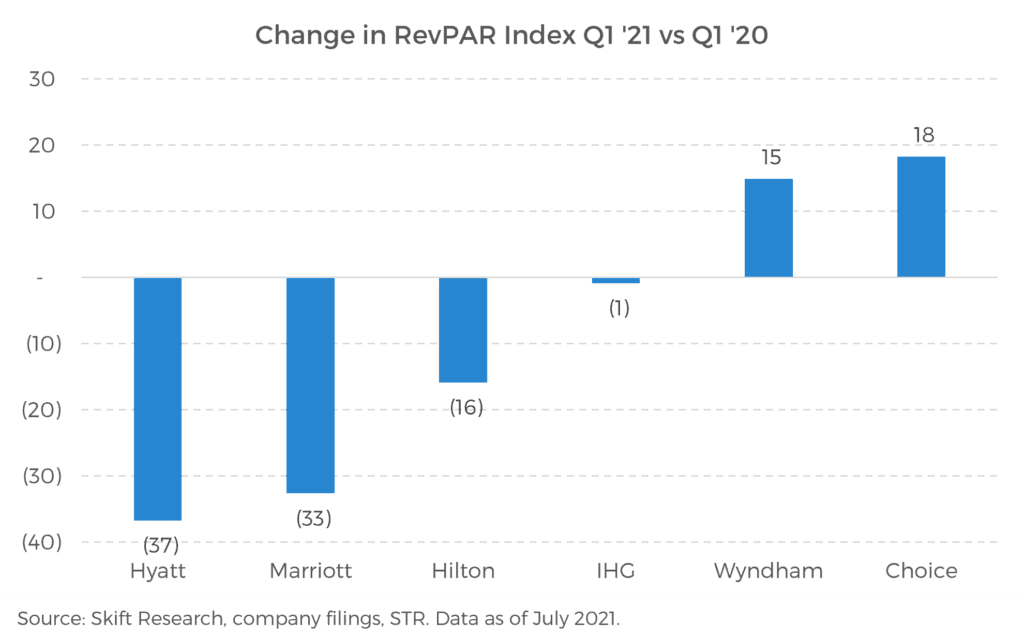

We also examined hotel franchise data from during the pandemic to see how U.S. brands performed during 2020. For our first pass, we collected quarterly U.S. RevPAR data at the corporate system-wide level. We then divided the individual company data by the full U.S. RevPAR data collected by STR.

This creates a crude version of the RevPAR index which indicates the relative performance of each brand compared to the U.S. whole market. By observing how each of the major brands’ U.S. RevPAR index evolved over the course of the pandemic, we can understand how their relative strengths shifted and by extension if they were out- or underperforming. And bear in mind, the peer set includes the 28% of the U.S. market that is independent.

Isolating just the change in RevPAR index from Q1 ‘21 where we stand today vs Q1 ‘20 which was mostly unaffected by COVID, gives us a good glimpse of how each brands’ relative strength shifted during the pandemic.

The largest gains were at Choice Hotels and Wyndham. The largest relative declines were at Hyatt and Marriott. We note that since all RevPAR changes in a given market must sum to zero, and because the strength at the brands we studied was not enough to offset the losses, there must be some other properties in the U.S. that posted large RevPAR index gains to close the gap. These could be coming from other brands we were unable to collect data from, or from independents.

Tony Capuano, the CEO of Marriott would disapprove of this analysis. On his Q1 2021 earnings call, he said that, “I’m not sure I’ve ever seen an environment where RevPAR index numbers are less relevant.” On the other hand, Patrick Pacious, CEO of Choice Hotels was very happy to talk up RevPAR index gains on his Q1 2021 call. Our chart probably helps explain the difference of opinion between these two CEOs.

Joking aside, we recognize that this approach has a major flaw because we are picking an overly large comp set. It is only meant to provide a broad outline of current market dynamics and not to be read too deeply into.

The strength at Choice over Marriott clearly reflects the relative performance of chain scales in the marketplace. The JLL data above shows that the economy chain scale has dramatically outperformed upscale ones. Choice skews towards economy brands while Marriott skews upscale. So this chart merely reflects the market positioning that each brand had built going into the pandemic and not the quality of decisions made by executives at either company. Nor does it necessarily explain which will be better positioned in the recovery.

A stronger analysis would be to construct tighter comp sets, limiting properties to their own chain scales, so as to see how an upscale brand compared against other upscale hotels. Unfortunately this data is more limited and we could not collect it for every franchisor in our initial analysis.

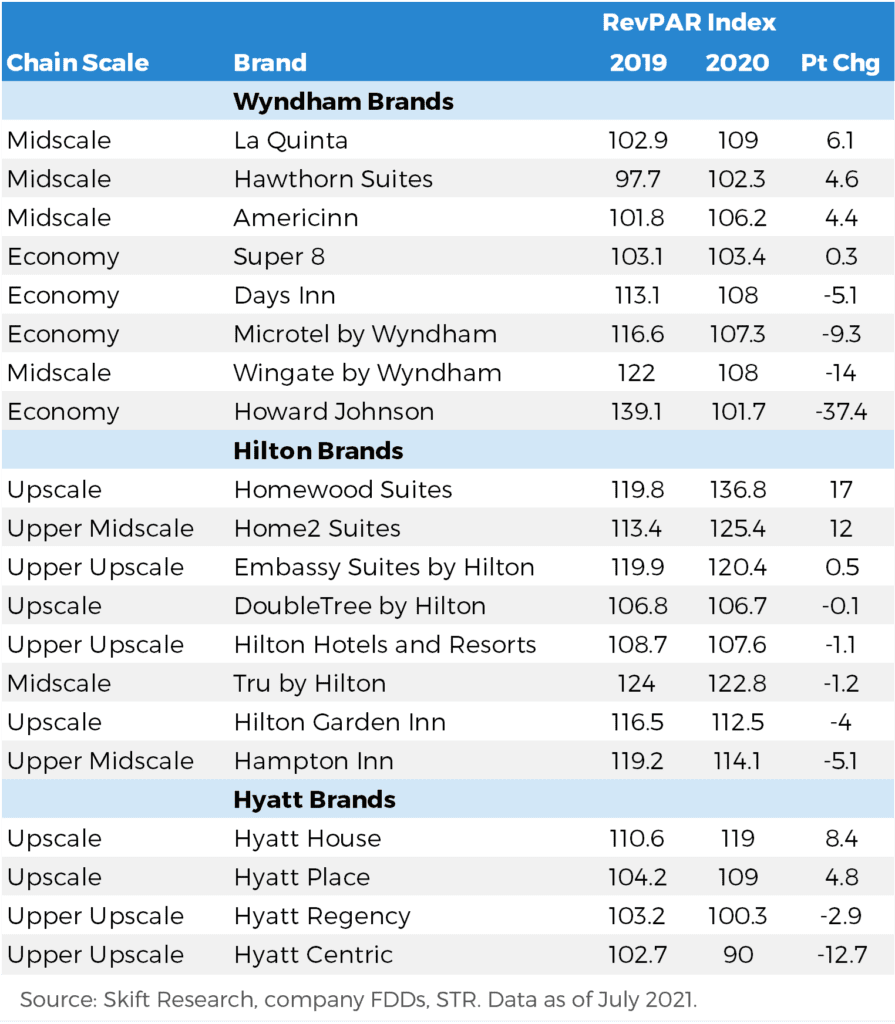

Still, we were able to collect RevPAR index data on 20 brands across the Wyndham, Hilton, and Hyatt portfolios. These RevPAR indices are specific to each brand’s chain scale and location. We compared how the RevPAR index changed from 2019 to 2020 to understand how these brands’ relative strength evolved during COVID.

Analyzing the data reveals no clear patterns across brands or chain scales. Most parent companies had a mix of brands that gained relative strength while others lost share. At some hotel companies, their midscale brands gained in relative strength, while at others it was the upscale segment. Though one through-line was that extended stay products grew dramatically.

Summing It Up

Our takeaway from this grab-bag of results is that brands were not a silver bullet to drive performance during COVID-19.

In many ways, even asking whether brands or independents did better during COVID-19 is a trick question. Our data clearly shows that some brands did better than independents and their peer groups while other brands did worse.

It was ultimately not the decision to be branded or not that mattered the most, but rather the unique combination of how each property was positioned in the marketplace. Was the property (or the brand as a whole) geared towards leisure or business travelers? Towards individual or group travel? Towards the south of the country or the west coast? Many of these decisions were made well before the pandemic.

But of course, when COVID struck, performance was often the result of how ownership and management responded. Were they able to show leadership, demonstrate agility, and react decisively? These factors mastered the most for hotel performance during the pandemic, far more than the generic decision to be branded or not.

Focus Topic: Staffing Challenges

Much of this report has focused on the different challenges and opportunities facing independent vs branded hotel owners. But regardless of which path you undertake, all hotel owners are facing one common challenge today: staffing. Hospitality’s growing labor crisis has been building for years as hotels struggle to find, afford, and retain talent.

The labor shortage temporarily abated as the hospitality industry laid off a huge amount of its staff and shuttered properties. Employment in the U.S. accommodation sector fell by a whopping -47% as 961 thousand hospitality workers lost their jobs between March 2020 and May of 2021, but only ~560 thousand of the nearly one-million lost hotel jobs have been brought back as of June 2021.

Then, the business was whipsawed by the faster than expected pace of Americans returning to travel. Seemingly overnight, the labor shortage was back and worse than ever. The accommodation and food service industry is now struggling to bring back staff. The combined super sector was looking to hire 1.25 million people in May 2021, which if filled would represent 9.1% growth in the sector’s labor force.

“Labor has been a tremendous challenge,” Saju tells us. “How do we get people back to work? How do we keep people motivated that are working? So they want to come to work and not leave for another industry.”

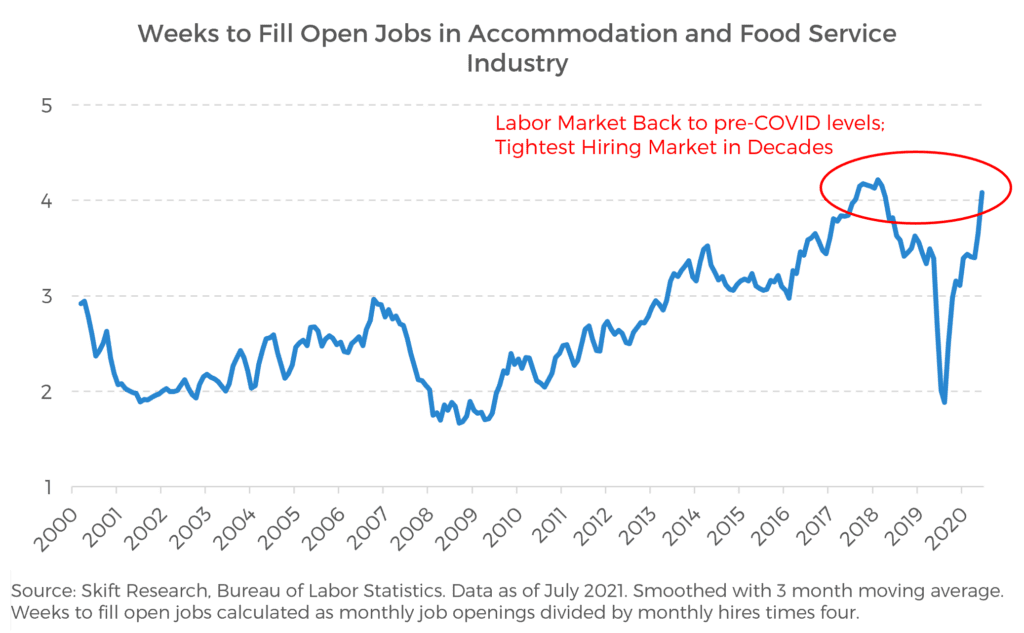

It has almost never before been as difficult to recruit for hospitality as it is today. It is taking hiring managers, on average, four-and-a-half weeks to fill their open positions vs. a more typical two-to-three weeks.

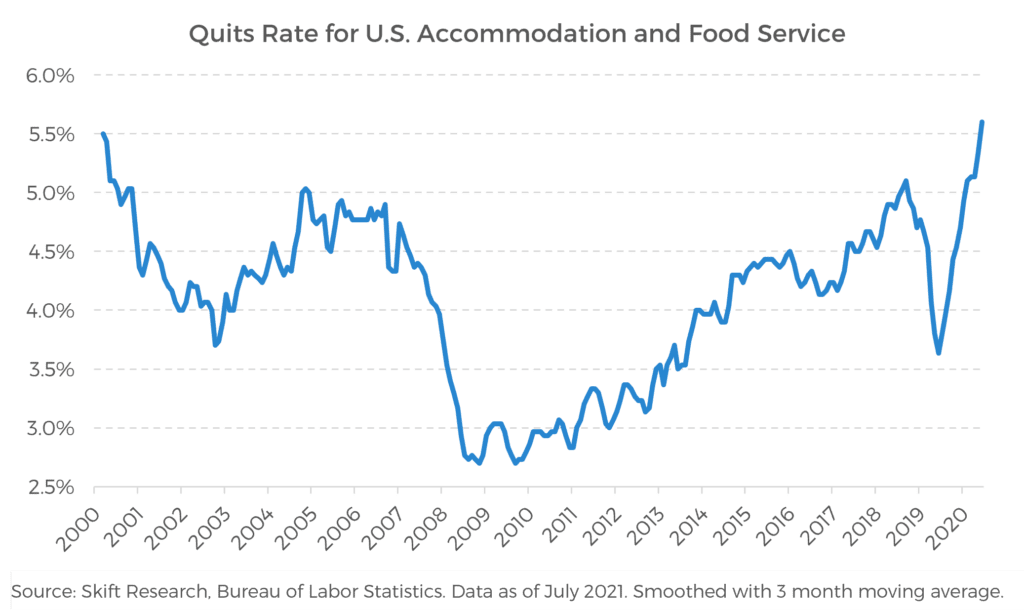

To make matters worse, the hiring process is leaking like a sieve. After taking over a month to recruit new staff, hiring managers saw 5.4% of their workforces, on average, quit in May 2021. This is the highest turnover rate for the industry in over two decades.

Some believe that the supplemental federal and state unemployment insurance benefits being offered in the wake of COVID-19 are making it difficult for hotel owners to incentivize their staff to return; in many states workers were receiving $15 an hour or more while on unemployment. Others blame the low wages in the industry and the more competitive opportunities opened up in other industries.

Regardless of your politics on this policy, the federal and state support is working as designed and has been consistently pointed to by nearly every industry participant we spoke with as a major hurdle in finding staff.

But with COVID benefits set to expire, this issue will be only temporary. Nonetheless, staffing headwinds are likely to persist. In many markets new job opportunities in outside industries, working in Amazon warehouses or at retail stores, are drawing workers away from hospitality. Amazon raised its warehouse minimum wage to $15/hr and Walmart has committed to paying its average worker $15/hr.

Plus, workers are simply disillusioned with the travel industry after COVID. Stung by mass layoffs, many left the industry in search of what they perceive to be more stable jobs. And those that did stick around are burnt out after 18 months of intense daily challenges. This makes good talent even harder (and more expensive) to find and retain.

With the endorsement of the two largest employers in America, competition from $15/hr entry base wages is likely not going away even once the COVID stimulus fades. And for context, the median wage for a hotel desk clerk pre-COVID was $12.26 an hour; housekeepers earned $12.18. Taken together these two positions account for ~37% of all jobs in the industry.

In fact, the median salary across the industry, including well paid executives, is $13.61/hour. Versus the rapidly emerging $15/hour baseline that means many hotel owners are looking at 10% or more labor cost increases on a go-forward basis. Labor costs are most operators’ largest expense item, running at ~30% of revenue at the typical hotel. We estimate it would take the typical hotel raising hotel room prices by 3% to offset these costs. In this case inflation could actually be a good thing for hotels. In Q2 2021, consumer inflation rose at 4.8% over the prior year. There are a lot of moving parts beneath the surface of this economic report but one silver lining is that inflation at this rate for hotels would allow owners to cover their rising labor costs while still growing or maintaining profits.

It seems likely that no matter how you slice it, the labor crisis in hospitality is not going away, and in fact, only getting worse. Talent is becoming scarcer and more expensive. This means that more than ever hotel owners will need to zero in on driving productivity and automations.

Though they often overlap, productivity is not the same as automation. Most hotels have seen large productivity gains during COVID as they realized they can run their properties on fewer staff. It will be essential not to over-hire as demand returns.

Hotels have effectively been given a chance to implement ‘zero-based budgeting.’ In this system, rather than plan next year’s budget as a variance from the prior year, the budget is built from the ground up, starting at zero with each expense being re-justified and re-approved.

We strongly encourage all hotel owners to adopt this approach in some form or another. And rather than plan hiring based on where staffing was in 2019, to instead consider each employee’s skills and workloads in this new normal environment and build staff from there. It is highly likely that you will find some function that can be removed entirely and other responsibilities that can be combined or delegated to existing roles.

But while this is a good way to trim the fat from the pre-COVID era, there are limits to how far this approach can take you as demand returns. To make structural productivity gains requires experimenting with new automation tools

Takeaways

The U.S. hotel ownership is harder to navigate today in 2021 than at perhaps any other time in history. Based on our review of the space, we close this report with five key takeaways for hoteliers.

- We’re Not Out of the Woods Yet: Travel demand is recovering but hotel owners are still not out of the woods yet. Demand is very unevenly split across locations, types of travelers, and chain scales. At the same time some leisure hotels are having their best summer ever, business hotels are still sitting vacant. And confuse a top-line recovery with a return to profitability. Hotel owners have dug themselves into a very deep hole, drawing down on cash reserves and taking out loans. With travelers hitting the road again, it’s more important than ever for hotel owners to be agile with their businesses to ensure success. Ironically for many hoteliers that survived the pandemic, it might be the recovery that does them in.

- Good Corporate Citizenship is Key to Navigating the Recovery: There are many stakeholders that hotel owners will need to work with to successfully run their businesses during the recovery. This includes banks, brands, management companies, staff, tech vendors, and guests. Most have been understanding of the unprecedented situation the hotel business has been through. But that may not last over the next several months. The keys to ensuring that you can retain the flexibility you need today will be: 1) clear communication, 2) a past track record of high performance in good faith, and 3) demonstrated actions to correct any outstanding issues. There may be some karma yet in this business.

- Consolidation is Coming: At the ownership level, Hospitality REITs and private equity funds are on the hunt for distressed assets. Ray Martz, CFO of Pebblebrook Hospitality told Skift, “There’s a feeling where there’s no distress out there in the world, the reality is there will be distress… Finally, when they’re [smaller hotel owners] done holding their breath, they’re going to have to sell, that happens. So we’ll take advantage of that. Others take advantage of that. It’s a natural part of the cycle.” At the brand level, conversions will be a major source of growth from the major franchisors. Historically this was the case, and we are already seeing it pick up again this cycle. By making use of conversion franchises brands and soft brands, we expect the franchised landscape to exit this crisis with even more of a room count market share lead than when they started.

- Brands Have a Place But Are Not a Silver Bullet: Brands are powerful tools. They make it much easier for hoteliers to get financing, attract customers, and find vendors. It’s fair to say that many small and medium sized hotel owners would simply not be in business if they were unable to work with a national brand. And it certainly felt good to have them in your corner during this storm. But that said they are not a silver bullet for all properties and all owners. Many independents did just as well if not better than the brands during COVID. This is especially true in an upscale, lifestyle focused niche where properties are distinctive enough to cut through the noise of the rest of the industry and charge a commensurate rate premium.

- Make a Plan, Don’t Be Reactive: The recovery is here and with it is a rapidly shifting hotel landscape. Norm Leslie, President of National Hospitality Services, gave us great advice, “If you own a hotel, give yourself a couple of days of quiet and just think about what you want to do over the next three years. Take ownership of where you’re going to be over the next three years today… You want to have a plan of action, because if you don’t, you’re going to get swept up.” We couldn’t agree more. Consumer expectations around safety and technology have permanently changed. Banks are under pressure to get their loan books in order and distressed investors are chomping at the bit. Brands are pushing conversions and their soft portfolios. Loyalty programs remain one of the most powerful distribution tools out there but new coalitions of independents are coming together to build their own tech and marketing solutions. Labor costs are rising and good talent is harder than ever to retain. How do you want to position your properties in this complicated market? Make a plan and be proactive about it; maintain flexibility, but don’t be passively swept along.