Executive Summary

With the global economic downturn and increasing trust of the Internet and online payments, there has been a major shift towards access of goods over ownership of them. The travel industry is the sector most affected by the meteoric growth of sharing and collaborative consumption.

The sharing economy is not new, but it has exploded in recent years thanks to consumers’ increased awareness of idle assets. Consumer-to-consumer vacation rentals and ride share bulletin boards have been around for years, but efficient online payments and trust in e-commerce have made sharing into a viable alternative for the mainstream. Startups like Airbnb, Carpooling and Lyft have enjoyed tremendous growth. They now operate on such a scale that they are matching mainstream hotels and transportation companies in convenience, and usually beating them on price.

The growth of collaborative consumption is not just about cash strapped travelers settling for a less luxurious option, however. In fact, it is growing in popularity for high-end consumers. Trust in strangers, and a desire to travel like a local rather than a tourist are also on the rise. Sharing and communing with locals is the best part of participating in collaborative consumption.

This trend has serious implications for hoteliers, rail, short-haul airlines, tour guides and destination marketers, but this doesn’t mean that they can’t incorporate the best of the sharing economy and stay relevant.

This trends report will look at the economic, social, and technological changes that drives customers toward the sharing economy, especially for accommodation and ground transport. Through an examination of the advantages of new sharing businesses, we will make recommendations for incumbent players in the travel industry to avoid disintermediation.

What the Sharing Economy Means to the Future of Travel

Behind the trend

The shift from ownership to access is transforming almost every industry, and travel is one of the most affected. Traditional travel providers should take heed and understand the market to remain relevant.

There are several names for the phenomenon of the sharing economy that are used interchangeably, including collaborative consumption and the peer-to-peer economy. Rachel Botsman, co-author of What’s Mine is Yours: How Collaborative Consumption Is Changing The Way We Live defines the phenomenon thusly: “Collaborative Consumption describes the rapid explosion in swapping, sharing, bartering, trading and renting being reinvented through the latest technologies and peer-to-peer marketplaces in ways and on a scale never possible before.”

Sharing and collaborative consumption in travel is nothing new, but a bevy of technological, economic and social developments have turned it from a counter-cultural, backpacker’s niche to a massive business.

Before the buzzword

Sharing unused resources or trading accessibility for money or in-kind is ageless. In travel, it is nothing new. Before buzz-worthy startups like peer-to-peer accommodation broker Airbnb appeared in the space, Couchsurfing, an early online social network, connected travelers with hosts willing to put them up free of charge in spare bedrooms or on couches. Couchsurfing still has 6 million members, but for the most part it mostly served a skint young crowd. Long before the web, Servas International, a non-profit founded in 1949 by a peace activist, did the same. Subscribers to Servas paid a nominal fee for membership and agreed to open their doors to other travelers in the network.

The modern sharing economy is for profit

“‘Commercialization’ of the sharing economy didn’t begin in 2007, if viewed as part of an evolution that began (for modern purposes) with the establishment of the Internet and, later, social and mobile technologies,” says April Rinne, Chief Strategy Officer at Collaborative Lab, who also leads the sharing economy working group at the World Economic Forum. “We began to share more, and different, kinds of things — often for money. First we shared bits of data, then email, then things like photos and movies and music, and — more recently — physical assets and experiences. So Airbnb today is, in some ways, a successor to photo-sharing and music-sharing sites of years ago, many of which were commercial as well.”

The European Commission report “The Sharing Economy: Accessibility Based Business Models for Peer-to-Peer Markets” says that an estimated $3.5 billion of revenue will flow through the sharing economy directly into users’ wallets, not counting the revenue generated by companies that facilitate the transactions. High-cost and low-use goods are the most likely things to be rented out, making accommodation and transportation prime candidates for disruption by this new model. Tuck Analysis found that of those who use one sharing category, 71 percent shared transportation and 20 percent shared travel accommodation. The value of private travel accommodation in Europe alone is projected to reach $15.4 billion by 2017.

Sharing unused resources or trading accessibility for money or in-kind is ageless. In travel, it is nothing new. Before buzz-worthy startups like peer-to-peer accommodation broker Airbnb appeared in the space, Couchsurfing, an early online social network, connected travelers with hosts willing to put them up free of charge in spare bedrooms or on couches. Couchsurfing still has 6 million members, but for the most part it mostly served a skint young crowd. Long before the web, Servas International, a non-profit founded in 1949 by a peace activist, did the same. Subscribers to Servas paid a nominal fee for membership and agreed to open their doors to other travelers in the network.

Drivers for growth of the sharing economy

In their 2011 book, Rachel Botsman and Roo Rogers identified technology, cost consciousness, environmental concerns, and a resurgence of community as the main drivers of the sharing economy. Dutch academic Pieter van de Glind confirmed this in a survey.

“Practical need, financial gains and receiving praise from others are the main extrinsic motives. The main intrinsic motives are social and environmental. Besides motivational factors, networks, (social) media and recommendation prove to be explanatory factors for the willingness to take part in collaborative consumption,” he writes.

Several major economic, social and technological changes that came about in the later part of the last decade made the sharing economy grow into a significant part of the travel industry.

Economic factors

Americans and Europeans know that relatives who lived through the Great Depression had a skill for thrift. People who deal with lean times tend to waste as little as possible, and reuse disposable items that others may throw away without a thought. This current generation of travelers who experienced the late 2000s economic collapse and subsequent fiscal austerity are similarly price and efficiency-conscious — but they have the tools to connect owners of transportation and space to those who need it.

“Renting and sharing allow us to live the life we want without spending beyond our means. Not all of it is intentional, mind you: low cash flow (or none at all) is most certainly driving many customers to rent rather than buy,” says Sarah Millar at Convergex Group, a brokerage. “Many of the sharing and rental services you can find on the Internet, for example, were founded between 2008 and 2010 — that’s not a coincidence.”

Academic studies of attitudes and motivations for participating in collaborative consumption point to economic benefits as the main driver. Juho Hamari and Antti Ukkonen of the Helsinki Institute for Information Technology found that money-saving is more prevalent for motivating people to participate.

“[Collaborative consumption] has been regarded as a mode of consumption that engages especially environmentally and ecologically conscious consumers. Our results, however, suggest that these aspirations might not translate so much into behavior as they do into attitudes,” they write.

Even those who aren’t directly affected by the rise in unemployment in rich countries since 2007 are eager to find ways to save on travel. While incomes stagnated, households had extra pressures such as mortgage debt, while the younger population in America struggles to pay off student debt. Meanwhile, gas prices, and therefore, airfare increased and hotel rates stayed the same. The growth of the sharing economy took place alongside declining rates of home and car ownership in the United States and Europe. The generation that came of age indebted may aspire to ownership, but it is willing to settle for access to such things instead.

Such travelers are more aware of idle or excess assets. Sharing allows owners to make money from their idle cars, reducing the cost of ownership, and gives potential car renters another option that is usually cheaper than a mainstream car rental. Thus, sharing expands options and helps people save money. A study sponsored by Airbnb found that 60 percent of adults agree that “being able to borrow or rent someone’s property or belongings online is a great way to save money.”

Another economic trend that contributed to the growth of the sharing economy is the prevalence of venture capital to fund the startups that champion the concept. According to a study of 200 collaborative consumption startups by Jerimiah Owyang at Altimeter Group found that they have enjoyed a collective $2 billion influx of funding. The average funding per company was $29 million. This enabled these new companies with novel business models reach a wide audience and grow very quickly.

Technological factors

Peer-to-peer transactions were once limited to one’s friends, family and immediate neighborhood. Mobile technology and social media make it possible to match supply and demand among a much wider network, and with a reasonable level of trust.

In the earlier days of the web, users mistrusted the people they met through it and it took some years before they were comfortable using the Internet to make monetary transactions. Movies involving computers from the mid-1990s painted new technology as a sinister world full of antisocial serial killers. Being able to trust a potential host is a big hurdle to getting into a car with or sleeping in the home of a stranger. Almost all sharing sites involve some sort of social networking feature to show users that those supplying the transport and accommodation are who they say they are.

Social networking takes the anonymity out of the transaction. In some ways, the sharing option is inherently safer than the traditional one. A case in point is the mobile peer-to-peer ride sharing service Lyft, which allows both drivers and those who they pick up to rate one another.

“People who use Lyft appreciate the ability to provide immediate feedback. It also takes the anonymity of it and holds everyone to a higher standard. It adds an extra layer of safety and trust because there is that accountability,” says Erin Simpson, a spokesperson for Lyft. “If you have a negative experience you can let the customer service team know in minutes. With a taxi, if you leave your phone behind, you know who you rode with and you can find that person.”

As sharing becomes more prevalent we should watch how users’ biases affect access to the services. The old economy has rules in place to protect access to hotels and ground transportation, no matter what the operators’ preferences or bigotries may be. But the new economy has no system in place to prevent racial or other forms of bias that would keep an Airbnb host from discriminating against certain users or a Uber driver from driving to certain neighborhoods.

Lyft is an example of collaborative consumption made possible by location-aware mobile technology. The program, which only works on a user’s smartphone, shows where ready, willing and able drivers can be found.

Online payment systems also took away opportunities for fraud. Newer sharing companies like Airbnb act as middlemen for the two parties. Older peer-to-peer models for vacation rentals and the like required the renter to wire money directly to the owner, which is perceived as riskier than going through an intermediary with a decent online reputation. Trustworthy online payments made sharing rooms more of a mainstream money saver compared to free couchsurfing.

Social networking also establishes trust with people who might be friends of friends (or acquaintances). Airbnb uses Facebook integration so renters and property owners could see what their actual friends say about one another and whether they have friends in common. London-based startup FoF Travel is exclusively based on helping travelers meet up with friends of friends while they adventure abroad. Right now, the site requires users to add only their most trusted friends rather than pull in the hundreds of tenuous connections that many have on Facebook, but they are considering leveraging users’ preexisting connections on the social network.

Social factors

Changing norms and consumer taste are also major drivers of the growth of the sharing company that traditional travel companies also need to track.

In contrast to the findings of Hamari and Ukkonen, a 2013 study by Ipsos Public Affairs commissioned by Airbnb found that the top motivation for a plurality of U.S. adults (36 percent) was philosophical beliefs associated with sharing. However, other studies demonstrate that the most likely motivator for those who have never used collaborative consumption was the money-saving aspect.

“Often people begin sharing as a way to make money, but we’re seeing that philosophical benefits and social connections are the reasons people come back time and time again,” said personal finance expert Farnoosh Torabi, in the press release for study. The bridge between online and offline communities are creating the virality and stickiness that is propelling the ‘Sharing Economy’ forward.”

Through the shared pain of the hard economy, coupled with a greater desire for environmentally sustainable consumption, and a desire to connect with other people — even strangers offline are important points for incumbent brands to recognize when appealing to this market.

“I think another reason why sharing is becoming so popular is because there has been this shift in people’s mindsets. Information is so much more accessible. People are a lot smarter now and more informed than ever before. There seems to be a strong and palpable backlash against big corporations and excessive capitalism and consumerism. More and more people are searching for ways to find meaning and balance out their lives,” says Krista Curran, CEO and founder of FoF Travel. “People seem to be realising and comfortably accepting that at the end of the day, people — your relationships and community — are what matter. And instead of hoarding and acting selfishly, why not share and help each other out?”

Sharing and travel accommodation

Vacation rentals and peer-to-peer accommodation are among the most prominent examples of the sharing economy in travel, but it does not yet represent a real threat to traditional hotels. Some hoteliers are proactively evolving to fit into this trend.

Differences between vacation rentals and peer-to-peer hotels

Renting out another person’s home is nothing new. Prior to the Internet, classified ads and listing services compiled rentals based on destination. Vacation Rentals By Owner (VRBO) has facilitated such transactions online since 1995. For a yearly subscription to the service, homeowners could meet potential renters and negotiate directly through the site. HomeAway, which was founded in 2004, consolidated several companies including VRBO that offer vacation rental classifieds. When buyer and seller agree, the former sends the latter a direct payment.

Jon Gray, Vice President of HomeAway North America says that a major difference between the vacation rental market and sites such as Airbnb is the type of owners that use it.

“HomeAway allows people to do something with a second asset. Some people buy homes before retirement and rent them until they reach retirement age,” he says. “The overwhelming majority is second homes that are rented most of the year, while the owner is there a few weeks a year. Most inventory is located in vacation markets near beaches and mountains.”

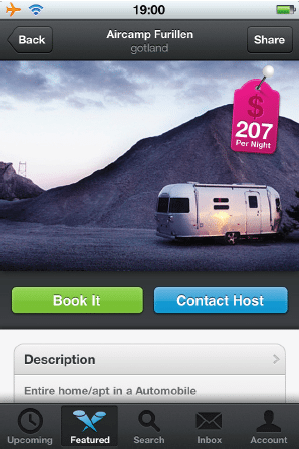

Airbnb, by contrast, is more popular with travelers and hosts in big cities. The founding story is that when a major design convention sold out San Francisco’s hotel rooms in 2007, two young designers decided to rent out three air beds on their living room floor. Those designers launched Airbnb in 2008 and it has since booked 10 million nights in 192 countries. It’s so popular that other startups in the sharing economy informally bill themselves as “the Airbnb of X.” Emily Joffrion, Airbnb’s Director of Consumer Strategy, says that as the business matures, less private couchsurfing-style deals are becoming less common. Most rentals are either entire apartments (which is illegal in the short-term in New York City) or a private room in an owner-occupied home.

Airbnb acts as more than a bulletin board for buyers and sellers to meet. Instead of charging owners or hosts to list available space, the company gets a portion of all transactions. Renters and hosts don’t exchange money directly, rather the renter pays Airbnb. The payment is debited 24 hours after check-in to ensure that the traveler isn’t charged for a room that isn’t as advertised. In lieu of a subscription fee, Airbnb takes 6-12 percent of the room charge, depending on the type of space and a 3 percent processing fee. In response to the success of this arrangement, HomeAway has begun offering a pay-per-booking model, too.

On the bright side, the company’s handling of the financial transaction takes some of the awkwardness away, and makes fraud less likely. If the traveler cancels at the last minute, Airbnb can hold them accountable. This also makes Airbnb the merchant of record for the transaction, much the same as a Hilton or Marriott is when you book a room. This draws scrutiny from tax authorities because they are responsible for covering taxes, but not all Airbnb hosts actually pay them. Airbnb directs users that earn a significant amount from renting rooms to fill out a 1099 form and pay the appropriate taxes.

Both allow guests and hosts to rate one another, but Airbnb only allows reviews from people who did business with each other.

Both vacation rentals and Airbnb-style peer-to-peer stays are on the rise. According to the MMGY Global/Harrison Group 2012 Portrait of American Travelers, in 2012 some 47 percent of American leisure travelers were interested in staying in a vacation rental home (46 percent in a condo) over the next two years, up from 44 percent and 46 percent, respectively, in 2010. The 2013 Vacation Collaborative Economy Report by Demeure says that 80 percent of U.S. travelers are comfortable with the idea of renting someone else’s vacation home on a trip.

Advantages of sharing for accommodation

Accommodation aptly demonstrates the economic and social advantages of the sharing economy.

Firstly, sharing is considerably cheaper on average than a non-discounted hotel room. In June 2013, Priceonomics, a company that helps companies crawl the web for data, found that Airbnb apartments cost 21.2 percent less than a hotel. Individual rooms are 49.5 percent cheaper.

Such a price advantage is attractive when the economy is still in recovery mode. Customers are hesitant to splurge when they are uncertain about future employment. Likewise, homeowners (and apartment renters) struggling to keep up with mortgage and rent payments are more willing to rent out their space to a stranger. According to Euromonitor, vacation rentals weathered the downturn better than hotels. In 2009, global vacation rentals declined 8 percent while the hotel industry fell 12 percent.

This could be a temporary change due to economic conditions, but younger people especially are becoming used to having access to more things than they could ever own.

“There are cycles in this business. We might be entering the cycle of doing things like locals right now but maybe five to seven years down the road, travelers might go back to wanting to be pampered,” says Frederic Gonzalo, a web marketing consultant for travel and hospitality brands. “Both can live in parallel. You can save on your own travel, but then opt to get pampered on the next trip with the family.”

Users of peer-to-peer travel tend to stay in a destination longer. In tan economic impact study, Airbnb found that visitors stayed in New York City for an average of 6.4 nights, compared to 3.9 nights for hotel guests. There is a similar case with Roomorama, which started out as a peer-to-peer network, but now specializes in high quality short-term rentals as a less expensive alternative to hotels. Jia En Teo, co-founder of Roomorama says that the average length of stay users is about three to four times that of a hotel guest.

Home away from home

Sharing economy customers appreciate the value of a more home-like environment, more space, and the relative lack of ancillary fees that come with sharing. Market research by HomeAway says that access to a kitchen, laundry and other home amenities are the number one reason that travelers choose not to stay in a traditional hotel. Being able to cook if so desired was the second-biggest reason. However, they found that a fifth of respondents say that wanting to get away from the routines of home life such as cooking and cleaning were reasons not to choose a vacation rental.

Such amenities go along with the absence of ancillary fees that hotels have come to rely on.

“Hoteliers are having a hard time, they have to reinvest in making their product up to par. They can’t increase rates, which have been more or less flat for over a decade and margins are shrinking,” says Gonzalo, the Internet marketing consultant. “In the traditional system, they might charge four bucks for a local call or wireless Internet access that only works in the room, but those fees are very frustrating.”

With more families traveling together for leisure, avoiding such fees becomes more important. Eurocamp, an upmarket camping and chalet company, reported that extended family bookings grew by 325 percent between 2009 and 2011. Brazilian tourists are known to take out entire hotel floors for a big family vacation. Renting a house or apartment saves money and allows different generations to have privacy and stay together.

Diversity and local flavor

The idea of sharing a local stranger’s apartment is very different from the old stereotype of the ignorant tourist that just snaps some pictures and leaves. This reflects travelers’ desire to live like a local for a short time. As a young traveler told Amadeus, travelers want to “go where we can meet the people and get to know the culture.”

“In the past, travel was about making people feel comfortable. In the show Mad Men, when Don Draper pitched a campaign for Hilton he offered slogans such as, ‘How do you say hamburger in Japanese? Hilton.’ Modern consumers want different authentic local experiences. They want to meet other people and make connections,” says Airbnb’s Joffrion. “This is a really big shift in the psyche of the consumer. I think that Airbnb is incredibly successful because we tap into what consumers want right now. I would say that more hotels and travel in general is going in this direction, offering more options around the lobby to connect with people staying there and programming around that.”

One way that sharing helps travelers connect with the lived culture of the destination is by expanding the stock of possible rooms outside of high-traffic tourist areas, giving them an option to get out of the tourist ghetto. Airbnb likes to state that 90 percent of its visitors stay in non-tourist neighborhoods, but this has never been independently verified nor broken down by market.

“People are spending a lot more time in a neighborhood and destination than they would at a hotel. They are contributing to the local economy, learning about their surroundings, traveling a bit differently than their parents’ generation,” says Roomorama’s Teo. “Even if as a guest you don’t necessarily want that sense of intrusion and living with locals for two weeks, when you rent a private apartment you still get that sense of being a local because you don’t have a concierge downstairs. You need to get to know the neighborhood yourself.”

The sharing economy also offers a better variety of types of accommodation. Castles, luxury treehouses, houseboats and private islands are among the structures that are in the reach of a sharing economy user.

A much better “concierge”

A major advantage that some peer-to-peer options have over hotels, is that the person who greets you at the door of her own home might not be a tourism professional, but she is definitely someone who knows the area well.

“I recently rented a houseboat in Amsterdam through Airbnb. There was a lovely young lady at the door, she told us about the area and recommended a fantastic traditional Dutch kitchen up the street,” says Troy Thompson of Travel2dot0, a travel marketing consultant. “The Airbnb host is a frontline worker in the tourism industry, just like a concierge.”

Guests get to know their hosts to some extent, and sometimes owe them some of their fondest travel memories.

“Airbnb has absolutely transformed my travel experiences – for the better – and is playing a key role in redefining travel writ large,” wrote April Rinne of the Collaborative Lab. “This crystallized brilliantly for me this holiday season. I spent Thanksgiving as an Airbnb guest in Kigali, Rwanda, and I hosted a family from Florida during Christmas week at my home in San Francisco, California. Both experiences were extraordinary.”

The challenge for hotels is approaching the same high level relationship with the actual concierge. As travel industry consultant Vikram Singh recently wrote in a blog post, “Expectations, questions and answers are exchanged between host and guest long before the check-in ever happens. This is how they make meaningful connections. Do I remember the guy who checked me into my last hotel room? Nope. Do I remember my last Airbnb host? You bet I do.”

But this does not represent all types of rentals on these services. The more popular listings in major destinations like New York and San Francisco are for rentals where the owner or host is not present. These are usually managed by a person who has multiple listings and makes a significant portion of his or her income from the rentals. In these cases the transaction and interaction is much more similar to a traditional hotel than an owner-operated bed and breakfast.

Key takeaways for hoteliers

First, the sharing economy should not be viewed as a threat to the hotel industry. The meteoric rise of sharing startups notwithstanding, they still make up just a small fraction of the one billion yearly U.S. room nights.

“The meteoric rise of Airbnb.com, booking more than 10 million nights since its inception in 2007, should not cause the hotel industry to worry about the vacation rental market. Both business models have co-existed for a significant amount of time without infringing on each other’s growth,” says Michelle Grant, Travel and Tourism Manager at Euromonitor International. “There may be a bit of a substitution effect with leisure travelers seeking out less expensive accommodation options during times of economic distress—which may be something hotels need to keep an eye on.

The much older vacation rental market is less of a competitor than a completely different service. IT is an example to learn from, not a threat. Grant points out that self-catering and private accommodation, the bulk of vacation rentals, accounted for $77 billion in revenue in 2011, up 98 percent since 1999. Total global hotel room revenue was $429 billion in 2011, up 83 percent over the same period.

Also, sharing sites work best in cities with already high hotel occupancy rates. For the most part, business travelers that adhere to corporate travel policies aren’t likely to have the choice of using a stranger’s guest bedroom.

Amenities: One place to start is to reconsider ancillary fees for Internet use and telephone calls. Guests are increasingly expecting connection free of charge. An obviously high markup for essentials like Internet use feel like even more of a ripoff after enjoying them for free on your last peer-to-peer rental stay.

Some hotels are coming around, says Gonzalo, the Internet marketing expert. He points to Kimpton Hotels’ loyalty program as a fine example. It gives you a minibar allowance, fee WiFi, and complimentary use of items such as hairdryers and computer chargers and complimentary toiletries such as toothbrushes.

Another perk that could make hotels more attractive, especially for families, is a kitchen. Gonzalo says that the Hilton Garden Inn’s suites with kitchen amenities are more consistently booked, and guests tend to stay longer.

Unique local experience: Staying in a hotel isn’t quite the same as living like a local and sharing their bathrooms, but hotels can still deliver a unique experience. Many hotels such as the Park Hyatt are offering one-of-a-kind local tours to guests. Some higher-end hotels such as the Ace are seeing success in attracting guests and locals to their lobby and restaurant. Inviting local musical acts to play in the lobby is one way to make the hotel stand out. Another possibility is inviting local chefs to give guests cooking classes.

In the past few years, there has been an explosion of sharing startups that allow residents in a destination to act as tour guides. If hotels partner with them hotel visitors could get a taste of the sharing economy and meet locals. Sharing startups such as Cookening, Bienvenue a Ma Table, and EatWithALocal that could give tourists an authentic experience that they might have with an Airbnb host.

Above all, hotels with a cookie-cutter experience will have a harder time appealing to the customers most likely to try sharing.

Personal connections: Not everyone wants a single-serve friend, but community is a strength of the sharing economy that could also work for hotels.

Extensive training for staff is more necessary than ever. Most guests come equipped with devices with access to almost all human knowledge. Staff should be at least as helpful with local knowledge. Boutique hotels have a huge advantage here. Joie de Vivre Hotels, one of the biggest boutique chains in the United States, is a fine example. Each JDV is unlike the others, and the concierge staff have detailed profiles and are encouraged to give guests personal advice. JDV’s founder and former CEO, Chip Conley, recently joined Airbnb as its head of global hospitality.

Hotels have inherent advantages: Hotels offer standardized service that make it appear safer than the sharing competition. Peer-to-peer accommodation rarely offers reliable instant booking. Many potential guests are put off by negative publicity about services like Airbnb, and don’t want to run the risk of having a bad experience with a property owner. In some cases, peer-to-peer accommodation is technically illegal. Older travelers are coming around to sharing, but are especially leery of interacting with strangers met over the Internet. With a hotel, there is an expectation of predictably good service and there is a clear answer for who can fix problems. Hotels must continue to leverage loyalty programs and branding while they incorporate some of the economic and social advantages of the sharing economy.

Sharing ground transport

As mentioned earlier, expensive items that are used very infrequently are the low-hanging fruit for the sharing economy.

According to RelayRides, a car-sharing startup, the average automobile is only in use for an hour a day, but costs as much as $715 per month. Assured Research says that the more than 200 million cars in the United States sit idle for 90 percent of their useable capacity. It is no wonder that environmentally conscious and cash-starved riders and car owners are eager to share ground transport.

The advantages of sharing transportation

Car ownership, even in America, is on the decline, especially among the younger set. The University of Michigan’s Transportation Research Institute found that in 2010, 69.5 percent of 19-year-olds had a driving license. This is down from 87.3 percent in 1983. In 2012, only 27 percent of new cars were purchased by 21-34 year olds. In 1985, that same age group bought 38 percent of new cars. Gartner, the research firm, found that 46 percent of 18 to 24-year-olds would chose Internet access over owning a vehicle.

A study by Paul Mang of Avarie Capital and William Wilt of Assured Research found that more than half of of 18 to 34-year-olds are likely to participate in a car share program, compared to 45 percent of those between 35 and 44. Only a fifth of the 45 to 54 cohort are likely to do so. Consulting firm Frost & Sullivan estimates that by 2016, about 4.4 million North Americans will use some sort of car sharing network.

Car and ride sharing are very appealing to those who are concerned about the environment. For long distance trips, it takes the empty seats that would be moving down the highway anyway and puts them to use.

Ridesharing

There are a number of startups that specialize in ridesharing, which is not unlike legitimized hitch hiking. Some are best for long-haul travel, and others operate more like peer-to-peer taxis.

Longer trips

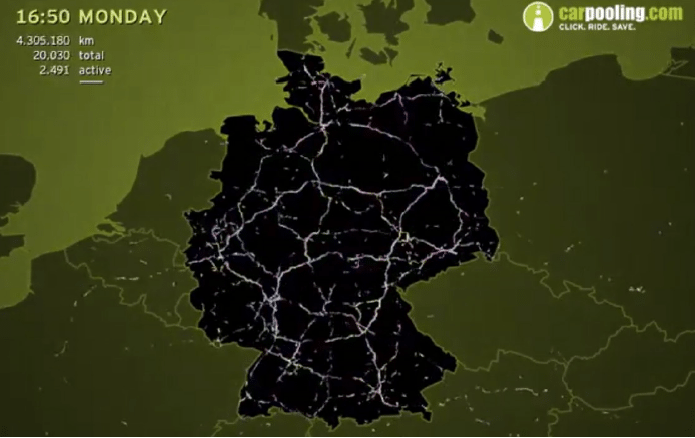

Intercity rideshares are already very popular in Europe. One leading site, Paris-based Blablacar, boasts 5 million members. Alec Dent, a spokesman for Blablacar in the U.K. says that 1 million people travel using the site every month, compared to 850,000 monthly passengers for the Eurostar train. Germany-based Carpooling.com also has more than 5 million members. In 2012, Carpooling.com transported 15 million people, almost half of Amtrak’s 31 million.

Blablacar and Carpooling allow travelers to pick up a ride to another city at a moment’s notice. Prices are dramatically cheaper than trains. Carpooling has a mobile app that shows you rides departing nearby, which removes the need to travel to a train station or airport rental car lot. You can book through the app very quickly and never have to exchange money in person. Blablacar’s prices are capped to ensure that drivers do not make a profit. For example, driving from London to Manchester costs about £45. If the driver fills the three empty seats in the car for the suggested price of £15, the trip is free for him. Both services are so popular that on big routes such as Berlin to Hamburg, you can find a ride departing every few minutes.

As with peer-to-peer accommodation, there is a social element as well. Spending time with a stranger in a small car might sound like a special type of hell for some people, but you can at least choose the stranger you ride with. Riders and drivers choose one another according to their ratings, the type of car, their driving style, and social networking profiles. Finding rides from friends of friends is a key feature of ridesharing.

“Carpooling gives you more price options, and a wide variety of cars to ride. Sharing a ride with another person to a business meeting, you can sit in the back seat of a BMW and work, and on the way back you can pick up a few snowboarders and listen to cool music,” says Odile Beniflah, who is a part of Carpooling’s expansion into the United States.

Beniflah says that despite ridesharing’s roots as a money-saving tactic for students and young people, 25 percent of their users are over 40 years old. The frequent strikes that disable French trains helped drive its popularity for all age groups.

Despite the success of ridesharing in Europe, it isn’t catching on at the same scale in the United States. For one thing, European cities aren’t as spread out as they are in America. Gas prices and the cost of train tickets are also higher in Europe. Zimride, which began as a Facebook app, has about 350,000 users, mostly on U.S. university and corporate campuses. Zimride was acquired by Enterprise, the car rental company.

Blablacar is leaving America alone for now, but Carpooling is preparing to launch Stateside next year. They believe that America’s car culture and the unlikelihood of national high-speed rail will make it a popular import. They point to a 2001 National Household Travel Survey which found that Americans take 2.6 billion trips of 50 miles or more every year. Nine out of 10 of these long-distance trips are by car.

Peer-to-peer taxis

The founders of Zimride also started Lyft, which allows car owners to operate like independent taxi drivers. Drivers with clean records can attach a furry pink moustache to the front of their vehicles and go to work whenever they like. Through a mobile app, riders can see nearby drivers, read ratings, and request a ride. Payment goes through the app, so no cash needs to change hands.

Immediately after launching in San Francisco, Lyft received a cease and desist order from the city.

“Their primary concern was public safety which has also been our priority to from the beginning,” spokesperson Erin Simpson said. Following a ruling in California this summer Lyft and others were forced to institute stricter guidelines for its drivers. “Lyft drivers must pass a criminal background check,” Simpson said.

Insurance and ride sharing

As long as you don’t make a profit, there is no issue with insurance and sharing your vehicle. Passengers are covered by the drivers’ insurance. In September, California regulated and legitimized the peer-to-peer taxi market. The California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) created the category of Transportation Network Company (TNC) to apply to companies like Lyft, Sidecar, and UberX, requiring them to follow 28 rules and regulations.

TNCs must require drivers to undergo a criminal background check and training, complete a 19-point inspection, and hold a minimum of $1 million in liability coverage. This is more than the traditional limousine industry is required to have.

Lyft riders originally paid a “suggested donation” of which 80 percent went to the driver, but recently moved to a mandatory fare model.

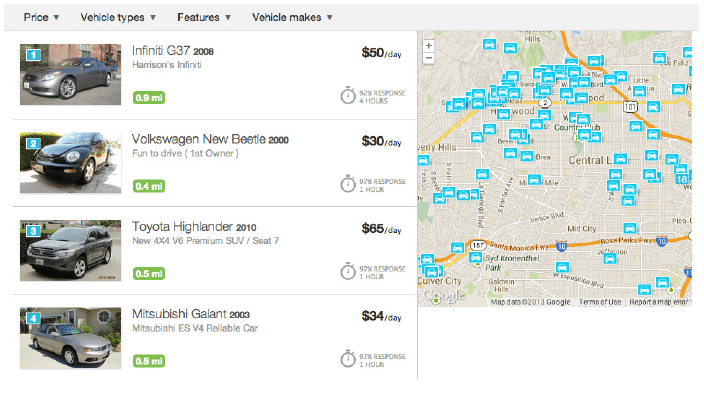

Peer-to-peer rental cars

Sharing companies are also disrupting the car rental industry.

RelayRides makes it possible to rent out another person’s car rather than patronize a traditional car rental. When you sign up, it does a check on your driving history to weed out bad drivers. On the website or mobile app, you can then choose based on price, proximity and the type of car. Vehicles listed on the site must have less than 100,000 miles and 10 years on them. After you find one that you like, and the owner decides to allow you to borrow it based on previous reviews of your punctuality and cleanliness, you book and pick up the car from the owner. The owner can rest easy because he enjoys $1 million in liability coverage through RelayRides.

“I think that what we have learned is that the transport side of the travel industry, especially for rental cars, has remained unchanged since inception,” says Steve Webb, a spokesperson for RelayRides. “By applying the efficiencies of the peer-to-peer marketplaces, we feel we are offering a superior product and making it possible to travel more inexpensively.”

Webb says that since RelayRides doesn’t pay for fleets and their management, RelayRides is usually 25 percent cheaper than the competition. RelayRides has cars available in all 50 U.S. states with the exception of New York, where the state Department of Financial Services says that it is not compliant with local insurance laws. The company hopes to address this when the state legislature reconvenes in January 2014.

FlightCar, another start-up, lets people get paid to park at the airport. The service, which is available in San Francisco, Boston, and Los Angeles, pays car owners for the right to rent out the car while they are out of town. Travelers who arrive typically pay about half the rate for rental cars from a mainstream provider. Their lot is located a few minutes outside of the airport, and FlightCar provides black car service between the airport and the lot.

There is also a monthly rental option for car owners who rarely drive. In return for agreeing to let FlightCar try to rent their car for at least 26 days per month, car owners get a check for up to $400.

Last month, RelayRides officially received permission to operate in much the same way at San Francisco’s airport. Like other car rental companies, RelayRides will pay 10 percent of gross profits and $20 per transaction to the airport. In June, the same airport filed a lawsuit against FlightCar for operating as a de-facto car rental company and refusing to pay those fees.

“I think that just like all the other peer-to-peer companies there are legal and regulatory headwinds blowing in our direction,” says Kevin Petrovic, FlighCar’s co-founder. “It’s a natural thing. If you institute a brand new model, it has a disruptive effect, you are going to encounter that.”

Mainstream car rental companies also have a toehold in the peer-to-peer space. Zipcar had invested $13.7 million in Wheelz, another car-sharing startup in 2012. This provides Zipcar’s parent company, Avis, with a stake in the sharing economy. General Motors aso led a $3 million round of funding for RelayRides.

What traditional transport companies could learn from ridesharing and peer-to-peer rentals

Vehicle variety: By renting out the cars that people actually drive, sharing companies offer the same level of variety as the actual road. This is how the sharing economy allows renters to affordably access luxury that would otherwise be out of their reach. If you are in the market for Mercedes or a cheap ride, you can find something that fits your style.

Convenience: It is possible to find a car or ride nearby rather than having to go all the way to the train station or airport to get a train or rent a car. This is one major advantage for Avis’ Zipcar, which has cars ready in multiple locations throughout cities where it operates.

Low price: The biggest advantage that the ridesharing option offers is a lower price than other options. Users are price conscious, and mainstream players could target those users for discounts. Carpooling.com gets a major revenue stream from making referrals to Deutsche Bahn, the national rail line. Deutsche Bahn targets Carpooling customers with options that might suit their needs better. The same could go for ground transport, low cost air carriers, and bus companies.

Social element: Some people are attracted to the personal side of the vehicle-sharing business, just as they are with peer-to-peer accommodation. Carpooling even claims responsibility for 16 marriages. When Zimride asked Cornell University students whether they would like to take a trip with a complete stranger, most said no. If that stranger was a fellow student at Cornell, they were much more willing to ride with them. However, we ride alongside strangers and share cramped spaces with them every time we travel.

Airbnb Vs. New York City: The Defining Fight of the Sharing Economy

The sharing economy, or as some call it the collaborative consumption economy, is still in its early infancy and companies like Airbnb, Lyft, RelayRides and their peers are the hottest topic in the startup world right now.

The legality of these startups has been in the grey from the start, as they push against the incumbent laws and regulations, and New York City, by being a dense urban environment where sharing comes naturally, has become a very high profile platform for some of these fights.

Airbnb is the biggest fight of them all, with rentals being a war game in our teeming city. Every generation that moves into New York City has its own rental stories, and ours is Airnbnb vs NYC.

Skift has covered all aspects of this fight, starting with our long investigative piece in January this year about the Airbnb and all the issues it has in NYC. Since then, that story has been cited everywhere and the headline number that half of its listings in the city are illegal has become the lingo among city and state lawmakers. Airbnb has fought back in some high profile cases, and is now girding for the long fight.

However New York City’s regulations shake out in this high-profile case, so will the rest of the nation and possibly the world over, at least in large cities.

We have kept a harsh light on all the sides and issues involved, and have done about 20 stories since.

The history of those issues, in links, in chronological order:

Airbnb’s Growing Pains Mirrored in New York City, Where Half Its Listings Are Illegal Rentals

Airbnb CEO Responds To Illegal Rentals Story: “First Of All, It’s Not Illegal Everywhere”

HomeAway CEO Sees Tough Short-Term Rental Laws As A “Nuisance”

Airbnb Host Will Have To Pay $2,400 Fine From New York City

New York State Senator Says Airbnb’s Actions “Pathologically Irresponsible”

Can Airbnb Really Hide Behind Its Murky Understanding Of The Law Until Its IPO?

Airbnb Gears Up For Big Legal And Legislative Battles in New York

What Is A Short-Term Rental? Leading Advocacy Group Isn’t Quite Sure

Airbnb Could Face Hotel Industry Class-Action Lawsuit as NYC Cracks Down

NYC Rules Airbnb Rentals Legal if at Least One Tenant Present

Airbnb Is Not off the Hook in New York City, Says Chief Legislative Critic

Airbnb CEO Gives New York His Three-Step Plan For Going Legit

New York State Attorney General Subpoenas Airbnb User Records

Airbnb Vs. New York City: Hosts and Users React

Airbnb Files Petition to Block NY Subpoena, Cites Burden to Compile Data

What HomeAway Can Teach Airbnb About Getting Along With Cities

1% of NYC Visitors Stayed in an Airbnb Rental Last Year

Airbnb’s Most Notorious Landlord Settles with New York CityWhat

Endnotes & further reading

- “The Sharing Economy: Accessibility Based Business Models for Peer-to-Peer Markets,” European Commission Business Innovation Observatory http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/policies/innovation/policy/business-innovation-observatory/files/case-studies/12-she-accessibility-based-business-models-for-peer-to-peer-markets_en.pdf

- “The Collaborative Economy: Products, services, and market relationships have changed as sharing startups impact business models. To avoid disruption, companies must adopt the Collaborative Economy Value Chain,” Jerimiah Owyang of Altimeter Group. http://www.altimetergroup.com/research/reports/collaborative-economy

- “From chaos to collaboration: How transformative technologies will herald a new era in travel,” Amadeus. http://new.amadeusblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/From_chaos_to_collaboration.pdf

- “Insurance in the Sharing Economy,” Paul Y. Mang, Avarie Capital and William M. Wilt, Assured Research.

http://www.assuredresearch.com/Insurance_in_the_Sharing_Economy.pdf - “The consumer potential of Collaborative Consumption: Identifying (the) motives of Dutch collaborative consumers & Measuring the consumer potential of Collaborative Consumption within the municipality of Amsterdam,” Pieter van de Glind, Utrecht University.

- “Trending with NextGen travelers: Understanding the NextGen consumer-traveler,” Amadeus.

http://www.slideshare.net/Chyan/amadeus-trending-with-nextgen-travelers - “The Social Traveler in 2013: A Global Review,” NH Hotels http://territoriocreativo.es/Social_Traveler_2013.pdf

- “The sharing economy: Why people participate in collaborative consumption,” Juho Hamari and Antti Ukkonen, Helsinki Institute for Information Technology.

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2271971 - “The New Kinship Economy,” Intercontinental Hotels Group.

http://library.the-group.net/ihg/client_upload/file/The_new_kinship_economy.pdf - “Young Global Leaders Sharing Economy Working Group Position paper, 2013,” World Economic Forum Young Global Leaders Taskforce.

http://www.slideshare.net/CollabLab/ygl-sharing-economy-position-paper-final-june-2013 - “Collaborative Consumption.”

http://www.collaborativeconsumption.com/