Report Overview

Hotel distribution is a complex process. In a market where demand fluctuates strongly, and a myriad network of channels compete for sales of the same room inventory, hotels need to understand how the different channels operate and have a clear strategy in place to allow for the best possible distribution of their rooms.

Skift Research has put together two reports to tackle this crucial element in hotel operations. In this first report, we focus on providing a greater understanding of the key issues that are shaping the channel mix, focusing on the major channels of direct booking, OTAs, and bed banks and wholesalers. We also discuss the role of metasearch engines.

Together with the second report, which will focus on the technology landscape and tech vendors that enable hotel distribution, this series provides a consensus view of the key issues and main opportunities for hoteliers, tech vendors, and distribution platforms to come out of the current pandemic-induced crisis.

What You'll Learn From This Report

- How hotels distribute their rooms to a complex web of channels, and how the COVID pandemic has impacted this

- How direct bookings have grown as part of the channel mix, and the importance of Net RevPAR

- The size and reach of the largest OTAs, and how their relationship with hotels has evolved

- The role of bed banks in the hotel distribution landscape, and how disruption might be coming

- How the hotel metasearch bidding process works, and why Google will only grow its influence

- How we expect COVID, and other disruptions, to impact the future of hotel distribution

Executives Interviewed

- Enzo Aita - Global Head of Business Development at Hyperguest

- Paul Anthony - Digital Commercialisation Director at Hotelbeds

- Katja Bohnet - Director of Hotel Distribution at Amadeus

- Tom Buckley - Co-founder and Chief Commercial Officer at Wildebeest

- Tom Corcoran - President and CEO at TCOR Hotel Partners

- Evan Davies - Founder at Channex.io

- Cindy Estis Green - Co-founder and CEO at Kalibri Labs

- Mark Fancourt - Co-founder at TravHoTech

- Mike Ford - Managing Director at SiteMinder

- Quinten Gazendam - Chief Growth Officer at SmartHotel

- Narcis Ghidanac – Revenue Manager at Me by Melia Dubai

- Pierre-Charles Grob - CEO at D-Edge

- Hamzah Hafesji - Senior Product Manager at Guestline

- Craig Hewett - Co-founder at Wego.com

- Christoph Hütter - Revenue Strategy Consultant at Christoph Hütter Revenue Management

- Shawn Jereb - Vice President of Revenue Management at Montage Hotels

- Chris Jones - Product Manager at Guestline

- Ullrich Kastner - Managing Director and Founder at MyHotelShop

- Steve Lowy - Founder and CEO at The Residence Apartments

- Bela Nagy - Senior Vice President Revenue Strategy and Performance at Accor

- Michaele Papenhoff - Managing Director at h2c

- Simone Puorto – Founder and CEO at Travel Singularity

- Amit Rahav - Co-founder and Chief Revenue Officer at Hyperguest

- Alexandra Fernandez Ramos - Chief Product and Sales Officer at Travelsify

- Murtaza Rangwala - Principal Consultant and Owner at RevUplift

- Karin van Rhee - COO at Juyo Analytics

- Sally Richards - Managing Director at RaspberrySky Services

- Joan Sanz - Founder at ChartOK

- Chinmai Sharma - President, Americas at RateGain

- Mark Struik - Commercial Director at Postilion Hotels

- Johnny Thorsen - Vice President Strategy & Innovation at American Express Digital Labs

- Monica Xuereb - Chief Revenue Officer at Loews Hotels

- Xabier Zabala - Global Operations Director at Hotelbeds

- We would also like to thank Michael Frenkel and Klaus Kohlmayr of IDeaS for their insights and industry introductions. Furthermore, we appreciate the teams at SimilarWeb, OTA Insight, Kalibri Labs, MyHotelShop, STR, and D-Edge sharing their data for this report.

Executive Summary

There is growing evidence that the current pandemic has impacted how hotel rooms are being distributed, with particularly the direct channels performing strongly. However, it is unlikely that these changes will be permanent, and in any case, the distribution mix has always been in flux.

Today’s hotel distribution landscape is intricate, with many players accessing and selling hotel room inventory through a myriad of channels. To understand the latest developments and issues that shape the distribution landscape, and how this might change moving forward, we interviewed 33 industry experts to share their views, including hoteliers, hotel consultants, channel representatives, and tech vendors.

In a nutshell, the most important channels for room distribution are the direct channels (such as the website, phone, and walk-ins), online travel agents (OTAs), and other third-party channels such as global distribution channels, bed banks, wholesalers, and consortia.

Since around 2016, Hilton, Marriott, IHG, and Accor have all spent valuable marketing dollars on direct booking campaigns, as well as re-asserting their loyalty programs, and offering discounts to their member bases. This push for more direct bookings has spread throughout the hotel industry and remains active today.

Data shows that direct online bookings have gone up over the past five years in the U.S., as well as in Europe and Asia. This growth has sometimes come at any cost, but there is a growing understanding in the hotel industry that data tracking should go beyond just revenue.

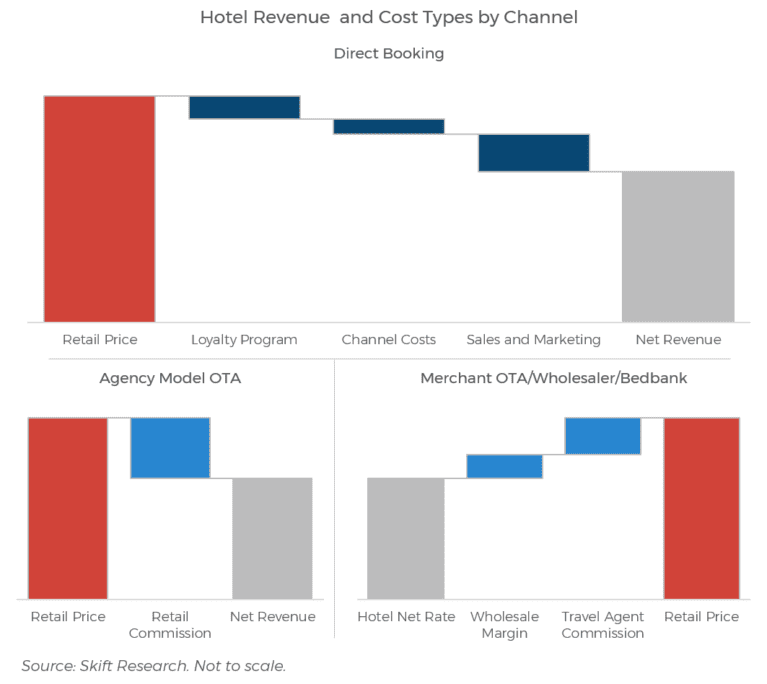

Revenue per available room (RevPAR), the key hotel indicator most used to determine the health of a hotel’s operations, is increasingly accompanied by Net RevPAR, to adjust for the costs of distribution. Particularly for direct bookings, costs to acquire a guests can be hidden or just not tracked, giving many hoteliers the wrong impression that direct bookings are always better than going through a third-party channel.

The main third-party channel that hotels increasingly rely on are the OTAs. Data shows that their share of distribution has grown over the past decades, and that their market power took a particular boost after past crises. The top 3 OTAs spent over $14 billion in marketing spend last year, making it impossible for most hoteliers to compete with. This marketing spend makes players like Booking Holdings, Expedia Group, and Trip.com some of the most powerful channels to attain new customers.

While there are many smaller OTAs, often working as affiliates with the large players, as well as alternative business models that are trying to capture some of the share from the major OTAs, we think it is unlikely that anything from within the travel industry will disrupt these players.

One player that might disrupt the major OTAs is Google, which has considerably strengthened its position as a metasearch engine since it entered the hotel space in 2010. The pandemic has seen the company roll out its commission-per-stay model which, with high cancellations, will be favored by hotels over the CPC or CPA models, further boosting Google’s strength in the distribution mix. Google has also voice capabilities which might completely alter how rooms are distributed within the next decade.

One distribution channel that is often mentioned as ripe for disruption is the bed bank and wholesaler space. Players in this space get discounted rates from hotels, and use their extensive network of travel sellers to sell the rooms while taking a margin. This channel has been hit hard by the pandemic, as it focuses predominantly on international higher-cost trips booked far in advance. The incumbent players like Hotelbeds are likely to regain their relevance after the pandemic, but their business practices will need to become leaner and more transparent.

Rate parity is one issue often equated with bed banks and wholesalers, as well as merchant OTAs. It is important for hoteliers to know what rates are out there on different channels, and we have seen steps by different players to start offering more transparency on this. Rate parity is likely to become less of an issue in the future.

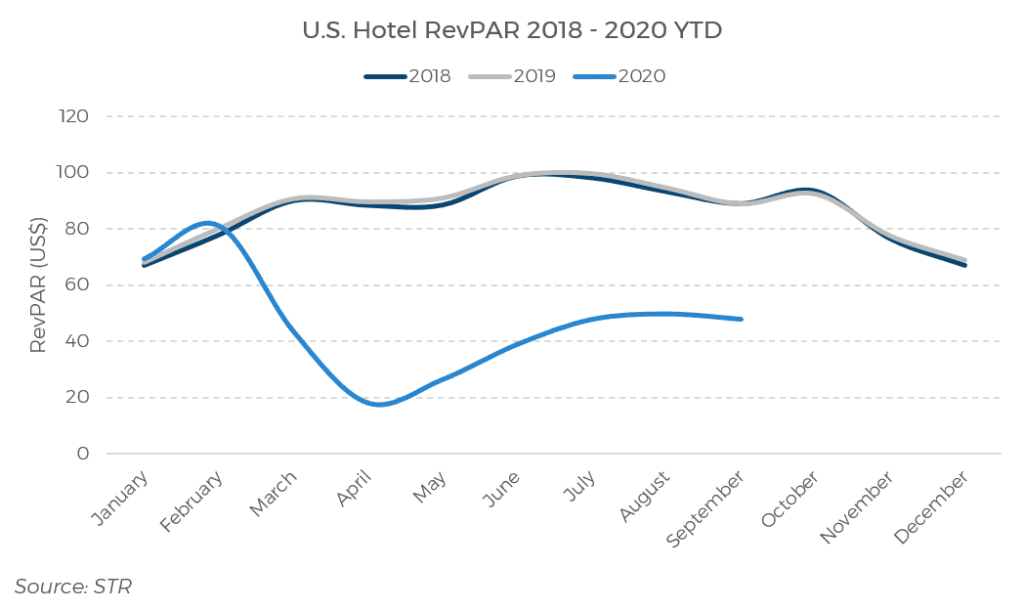

COVID pulls the handbrake on travel

The current COVID crisis has resulted in major slumps in hotel performance, forcing hoteliers to make tough decisions on shuttering their properties, making cutbacks, and laying off personnel. Service standards and expectations, as well as operational processes, have been redefined, maybe for good.

Anecdotal evidence provides an indication of the impact the current crisis is having on the hotel distribution landscape. The channel mix — also referred to as distribution mix or market mix in the industry, referring to the mediums and platforms used by hoteliers to sell their rooms to consumers — is always in flux. But over the past decade there has been an increased reliance on online travel agents (OTAs), and in more recent years a pushback against this, with a growing impetus on increasing direct bookings where consumers book their stays directly with the hotel using its own website booking engine or other direct means.

As a starting point we can look at a Skift Research survey that was conducted at the end of 2017, and which found considerable variation in channel performance depending on the hotel type. Large branded properties saw a typical 60% of bookings coming through direct channels, with an even split between online (unpaid and paid direct) and offline (phone, email, walk-ins, group). In comparison, independent hotels relied for an estimated 35% on direct bookings. OTAs played a much bigger role for independents, accounting for 40% of bookings, compared to 13% for branded properties.

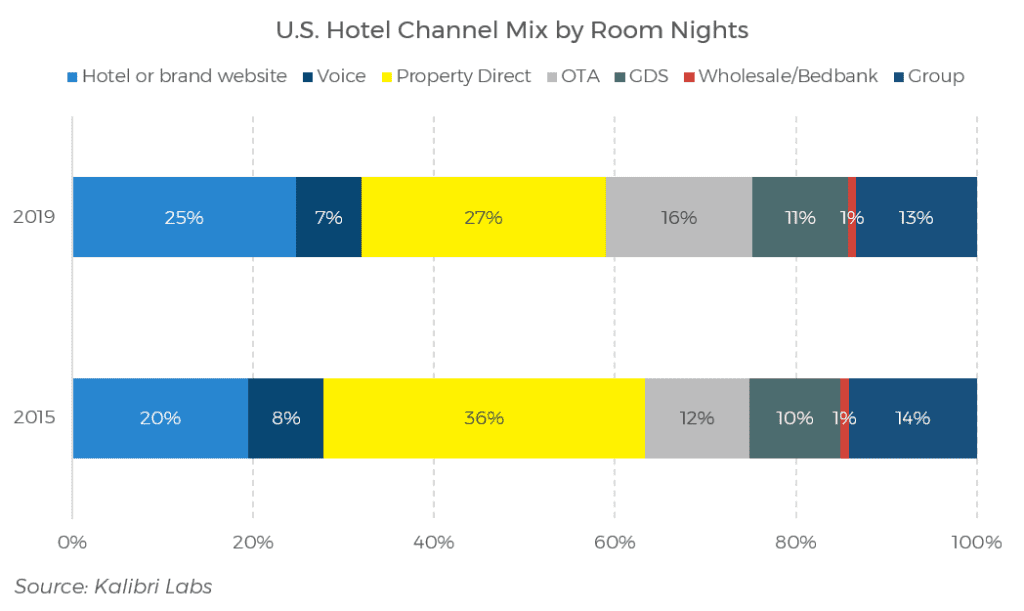

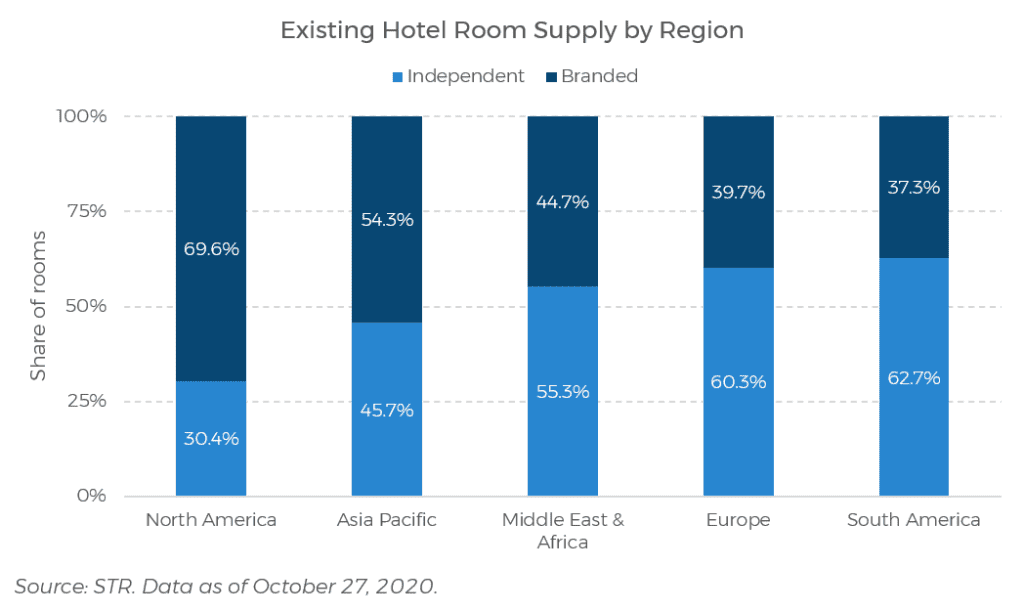

It is also interesting to look at the channel performance by region. In the U.S., where around 70% of hotels are branded according to STR, the hotel and brand website is an important, and growing, channel according to longitudinal data from Kalibri Labs. OTAs have grown their share in the channel mix as well, at the expense of property direct, which includes offline channels like walk-ins and contract business.

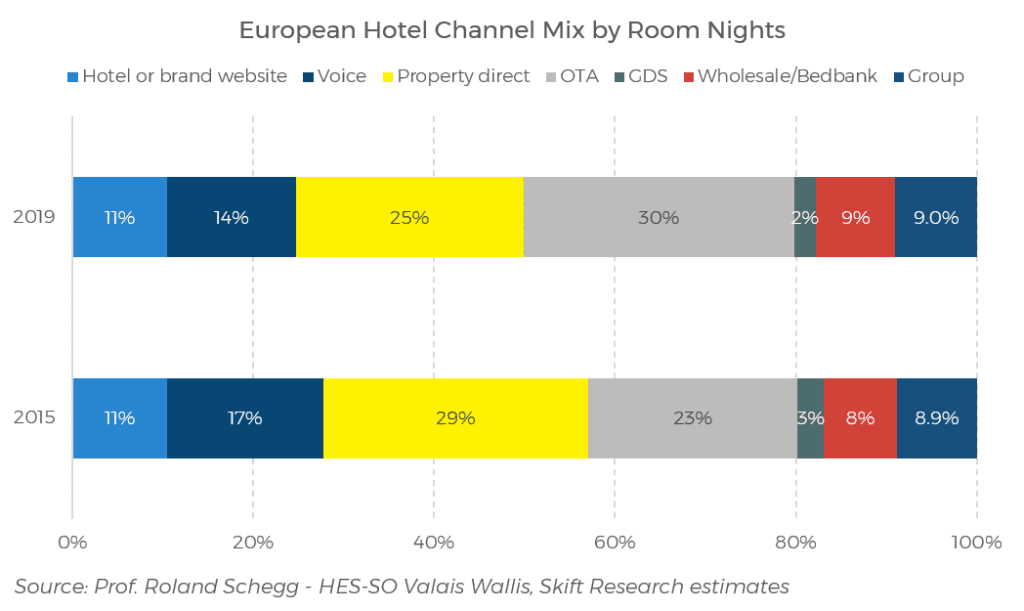

In contrast to the U.S. market, the European hotel landscape consists of many more independent hotels, and a study amongst mostly independent hotels by Professor Roland Schegg highlights how OTAs are far more prevalent in the channel mix for these hotels, and their penetration has grown considerably over the past years.

COVID-19 seems to have bolstered direct bookings, and phone calls in particular (referred to as ‘voice’ in the industry), with many consumers having questions and wanting the direct contact with the hotel. One interviewee told us that hotel bookings made through voice were up by 10% since the pandemic started. Separate from that, chat and text messaging was up “thousands of percent above what they used to be,” said the same hotelier.

Pierre-Charles Grob, CEO at hotel software vendor D-Edge, said that, according to a study the company conducted: “Customers give preference to the direct relationship with hotels, especially during times of uncertainty with restrictions and fast-changing regulations. Guests prefer to book direct on the hotel website and be in direct contact with their hotel.”

Cindy Estis Green, co-founder and CEO of Kalibri Labs said that: “There may be a temptation to leave all faucets wide open, but the data indicates that the loyalty member and other direct promotion rates are playing to hoteliers’ advantage; they should leverage that fully before taking on the high costs of third party business.”

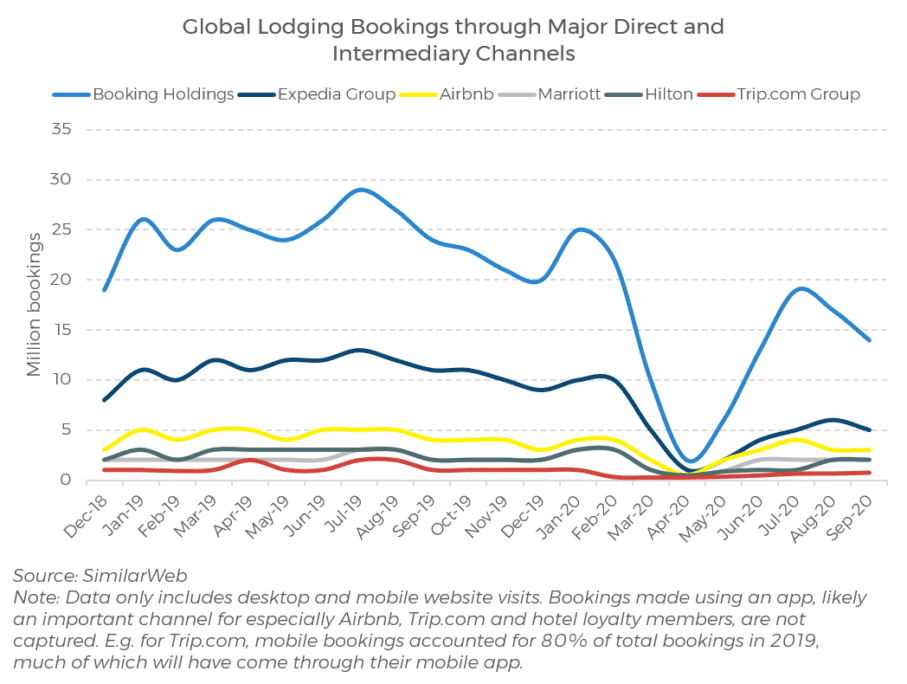

There are, however, signs that these third-party businesses, and especially OTAs might have strengthened their position during the pandemic, as they continue to provide the most up-to-date and extensive view of open and available accommodations — including hotels, but also vacation rentals which have been increasingly popular. Data from SimilarWeb, which collates desktop and mobile website visits to the booking confirmation pages of main hotel and OTA domains (as a proxy for bookings made), shows that especially Booking Holdings, while hit hard by the pandemic, saw a strong rebound in the months following the April trough.

Any hotel or channel focused on business travel is currently struggling, especially felt by the global distribution systems (GDS) in the channel mix. Travel agencies and tour operators with a focus on packages, group travel, and international trips, as well as the bed banks often used by these providers, are also hit hard.

It is unlikely that these shifts will be fully permanent, but it is certain that the current crisis provides both challenges and opportunities for hoteliers and channel providers as we move forward. Not only will some players be able to strengthen their position in the channel mix, while others might waver, hoteliers have been forced to utilize new distribution channels, market to new customer segments, and evaluate the technology stack used to ensure the best possible room distribution.

There is a real understanding in the hotel industry that these newfound experiences should not go to waste. Over the past years, for many hoteliers, hotel distribution has increasingly felt like being on a runaway train unable to reach the breaks. COVID has pulled the emergency break on the entire industry, and offers some opportunities for a reset, at least partially.

To understand which issues have shaped the distribution landscape, and how this might change moving forward, we have interviewed a host of industry experts to share their views. Our expert pool encompasses all parties that share an interest in the future of hotel distribution, largely falling within the following three categories:

- Hoteliers and consultants to the hotel industry. They provided insights around their channel mix, their methods of distributing, their struggles and frustrations, and they evaluated the technology they use.

- Channel representatives. Different players that make up the channel mix, including OTAs, bed banks, consortia, travel agencies, and metasearch providers shared their vision, and responded to criticism lodged by hoteliers.

- Tech vendors. Technology providers gave their insights into the tools they are producing to help hoteliers distribute their rooms more efficiently.

We put together two reports to tackle this crucial element in hotel operations. In this first report, we focus on providing a greater understanding of the key issues that are shaping the channel mix, focusing on the major channels of direct bookings, OTAs, and bed banks and wholesalers. We also discuss the role of metasearch engines. Together with the second report, which will focus on the technology landscape and tech vendors that enable hotel distribution, this series provides a consensus view of the key issues and main opportunities for hoteliers, tech vendors, and distribution platforms to come out of this crisis stronger.

Distribution landscape overview

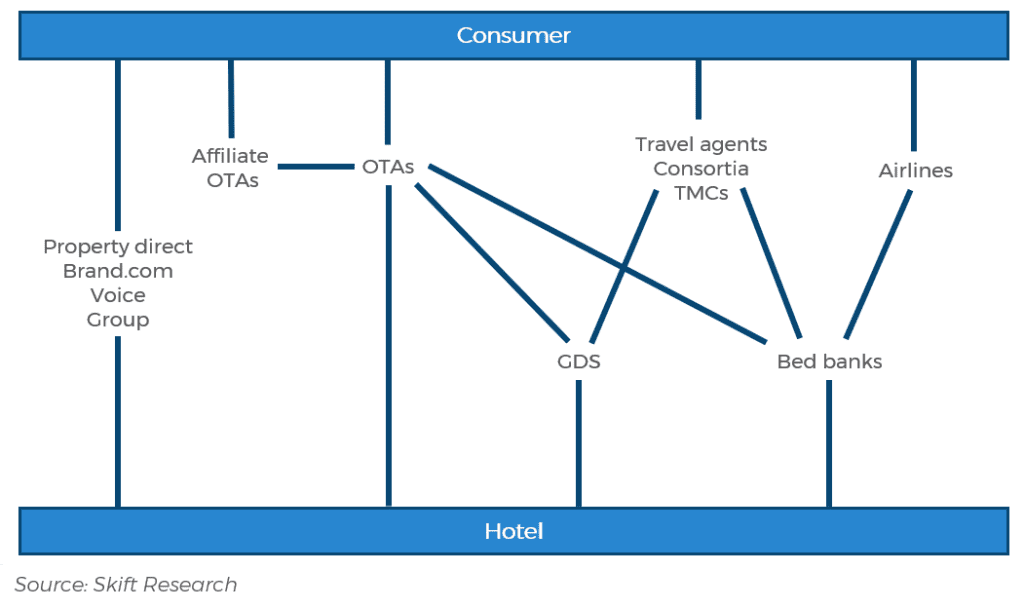

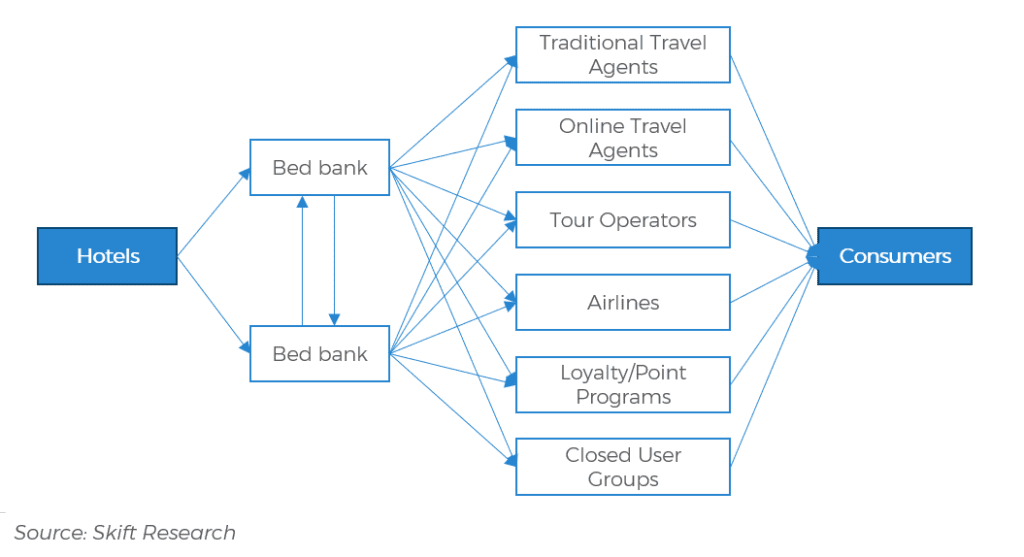

Today’s hotel distribution landscape is intricate, with many players accessing and selling hotel room inventory through a myriad of channels. Below is a simplified version of the main connections between the largest business-to-consumer (b2c) and business-to-business (b2b) channels.

This is used as a guide only, for further discussions in this report. Undoubtedly, lines between players in the distribution landscape are blurring. Traditional travel agencies and tour operators are increasingly closing brick and mortar shops, while they see sales moving online, blurring the lines between travel agents and OTAs.

Bed banks and global distribution systems (GDS) are increasingly offering travel agents with direct links to OTA inventory. Aggregators like TravelgateX collate inventory from different bed banks and OTAs behind a single connection.

Metasearch engines like Tripadvisor and Google would have had to scrape prices from across the internet up until recently, but here direct connections are also being built.

All these additional connections have greatly increased reach and visibility of hotel rates. While good for consumers, it is making it increasingly hard for hoteliers to keep tabs on all the distribution channels that are selling their rooms and at what rates.

We will dive deeper into the most important parts of the channel mix in the following sections.

Direct Bookings

Brands focus on direct bookings

Up to the early 2000s, hotel distribution consisted predominantly of people calling or walking into the hotel they wanted to stay in. For the vast majority of hotels, this channel, which is referred to as ‘property direct,’ represented between half and three quarters of their sales. Call centers, especially for branded properties, were also of significant importance. The remainder would be booked through travel agents, tour operators, consortia, and GDSs.

In 1996, Microsoft founded Expedia, and the Dutch startup bookings.nl was launched. These two brands — with bookings.nl changing its name to Booking.com in 2000 — became the main pillars of what today is sometimes referred to as the OTA duopoly between Booking Holdings and Expedia Group.

The online travel agents received a boost in 2001 during the aftermath of 9/11, when demand was low and hotels were happy to release much of their inventory to these online channels. With more and more travelers booking online, and another downturn in 2008/09, the OTAs’ share in the channel mix continued to increase.

To combat this, major hotel chains started to launch consumer facing campaigns which promoted booking directly with hotels. From 2016 onwards, Hilton, Marriott, IHG, and Accor have all spent valuable marketing dollars on these campaigns, as well as re-establishing their loyalty programs, and offering discounts to their member bases. This push for more direct bookings has spread throughout the hotel industry and remains active today.

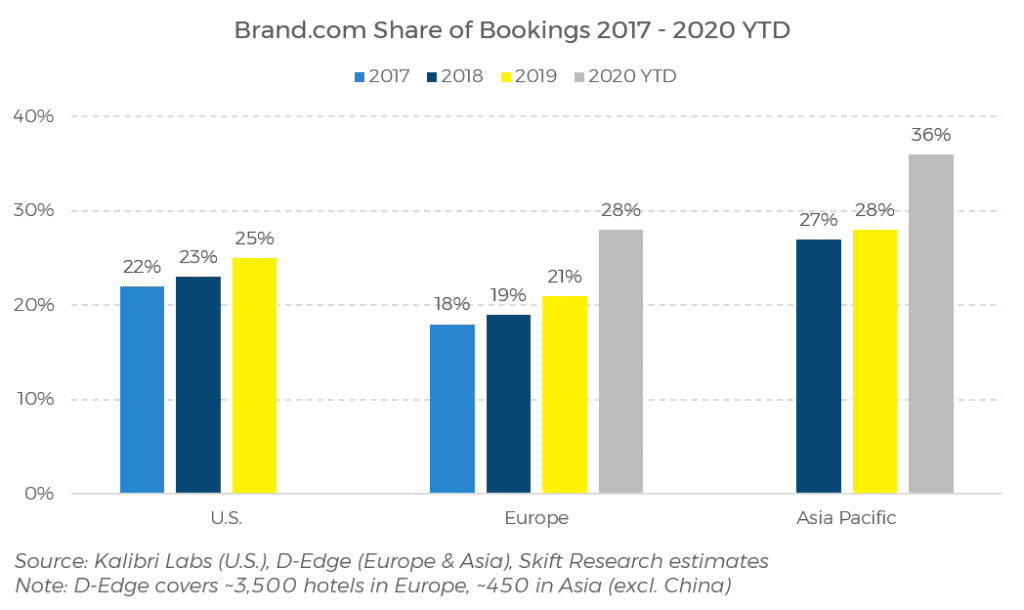

An analysis of channel distribution for U.S. hotels by Kalibri Labs shows that the direct booking campaigns certainly had an impact over the past years. A similar picture is painted by a new study from D-Edge, which focuses on Europe and Asia Pacific. D-Edge data runs up to September 2020 and shows that the pandemic has resulted in a major boost for brand.com bookings, which were already up over the past years. Based on anecdotal evidence, we expect that the 2020 growth in brand.com bookings in Europe and Asia will be mirrored in the U.S.

The importance of loyalty members

During Marriott’s Q4 2019 earnings call, CEO Arne Sorenson commented that as much as 75% of all bookings for its franchised hotels came through direct channels, be it bookings made through its online website or app, rooms booked through its call centers, or group sales. Around 33% of total bookings were made through direct digital channels.

This is a very strong showing from Marriott, but not necessarily representative of the wider industry, as we have already alluded to above. These numbers are much higher than any independent or small chain can expect.

In the hotel industry, the distinction between branded and independent hotels is often made, and when it comes to distribution this is an important consideration to keep in mind. It not only impacts what the channel mix of individual hotels looks like, but also how entire regions consider and deal with different channels.

Data from STR shows that the North American market is by far the most branded in the world, whereas Europe is extremely fragmented.

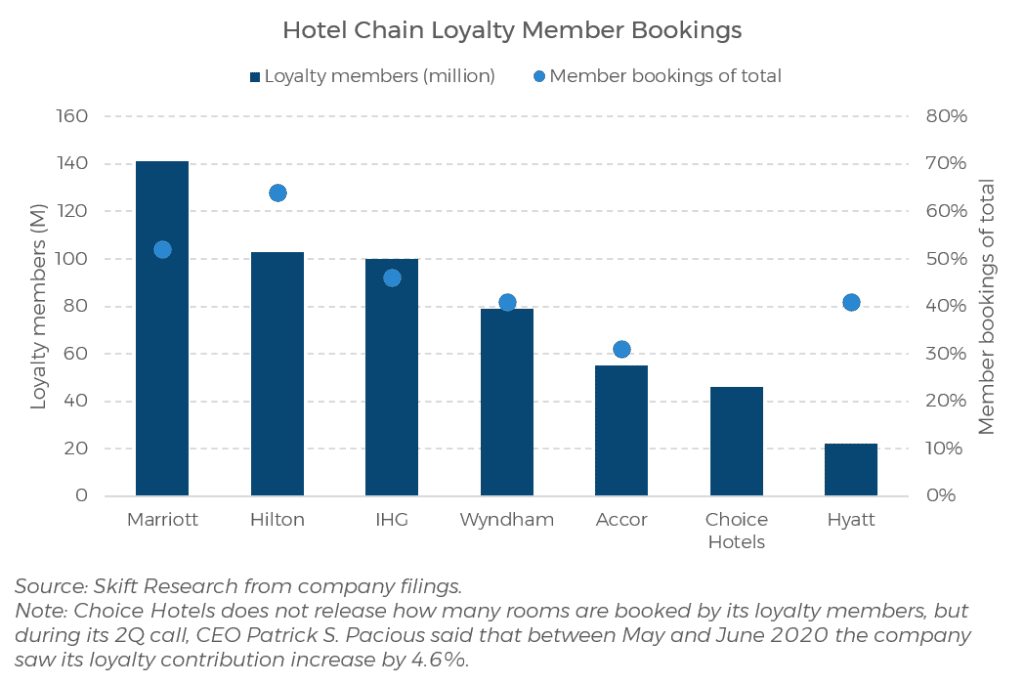

One immediate impact the reliance on brand flags has is the proliferation of bookings made by loyalty members. Guests who are part of a hotel chain’s loyalty program tend to book more often, and they generally book direct.

This is a major factor in hotel chains pushing direct bookings in the first place, because a loyalty member will, over time, be cheaper than the 15-20% commission fees most hotels pay OTAs. The exhibit below shows how most chains are reliant on loyalty members for 40-50% of their bookings, with Accor slightly lower and Hilton higher at almost 65%.

The cost of direct distribution

Due to these high percentages of bookings made by loyalty members, chains have a natural head start when it comes to direct bookings, something that has been touted as the cheapest way of distributing rooms. There is, however, a growing understanding amongst hoteliers, especially those running small or independent hotels, that this is not necessarily the case.

Discussions in the industry predating the pandemic often focused on the direct booking question, with a growing push for hoteliers to move beyond revenue per available room (RevPAR) as their most important key performance indicator, and instead to focus on Net RevPAR, taking the cost of distribution into consideration.

No doubt, the major hotel chains have wisely invested in brand promotion, loyalty program expansion, and booking technology to increase direct bookings, as at their scale it really does make a difference once they can tie a customer into their loyalty program. However, for the vast majority of hotels, a 15-20% commission might just be a fair price to pay for reaching a new customer, once we consider the alternative.

“Right now to get a direct booking, you need probably a proper metasearch strategy, some money on social media, some money on search, you need a booking engine, you need a channel manager, you need so many technologies,” said Simone Puorto, founder of hotel tech consultancy Travel Singularity.

Beyond technology, call center or sales representative wages should also be considered. Potentially, wages of staff who need to manually extract bookings from one system and input it into another when technology doesn’t work as seamlessly as promised add further costs. And consider the freebies and discounts given to direct bookers or loyalty members.

Loyalty redemptions have a cost attached to them that hotel owners pay to the brand flags, and it ties hotels into offering certain rates to loyalty members which do not always follow demand dynamics in the market, therefore potentially resulting in lost revenues. All in all it is clear that it is easy to spend more than 20% of the guest-paid revenue on acquiring a direct booker.

Ullrich Kastner, managing director and founder of MyHotelShop, an online marketing agency for hotels, notes how hoteliers have a few ways to increase direct bookings. “If you want to increase your direct business, you have three levers. Lever one is more traffic, lever two is a higher conversion, and lever three is a higher [room] rate. As simple as that.” More traffic to the hotel website, or a higher conversion rate — that’s the amount of people that actually book once on the hotel website — comes with additional costs. There are many online marketing agencies, website and booking engine builders, or conversion specialists that can help with this, but they come at a price.

With retail OTA players like Booking.com or Expedia, the commission rate is pretty transparent — as long as the hotel revenue manager does not take part in OTA promotions which come with an increased commission rate. The hotel sets the rate at which it wants to offer rooms to consumers, and once sold, the OTA takes a share of the retail price.

Wholesalers work in much the same way, with the only difference that they tend to request ‘net rates’ from hotels. This in effect means that the hotel provides the wholesaler or bed bank with a discounted rate, to which the wholesaler/bed bank adds a margin for itself and the travel agent, and then sells to the consumer.

Direct costs are generally harder to track. And the question is how far to go down the rabbit hole. As Shawn Jereb, vice president of revenue management at Montage Hotels said: “I wish we could [track it], but it’s nearly impossible and it always raises the question … how do you associate all costs into the channel distribution when it’s not obvious?”

So while there is a growing understanding of the importance of Net RevPAR amongst hoteliers, too few make it a key indicator and track it consistently. Most still rely heavily on guest-paid revenues as the most important indicator of their hotel’s performance.

Moving towards Net RevPAR of course needs to remain a workable solution. One reason hotels use RevPAR as their key indicator for the health of their business is the ease with which they can track this consistently. In today’s data age, however, it is important for hoteliers to, at the least, start tracking the different net revenues that they achieve through different channels, taking note of the most important cost factors within each.

As Karin van Rhee, chief operating officer at Juyo Analytics, a business intelligence vendor which focuses on helping hotels visualize their Net RevPAR, put it: “I’m not saying we need to count every croissant at breakfast, but you need to be able to compare apples with apples and not say direct is for free, OTA is 15%.”

Online Travel Agents

The growing strength of the OTA triopoly

Hotel associations like AHLA have been aggressive in their lobbying against what they refer to as the OTA duopoly — the power of the two largest players Booking Holdings and Expedia Group. The idea that OTAs are the enemy of hoteliers is much reported, but far from the prevailing view amongst hoteliers today.

While there are always hotels that are over reliant on business coming through OTAs, the interviewees we spoke to all acknowledged the value of OTAs in reaching consumers which the hotel would never be able to reach for the price of the average commission. As Monica Xuereb, chief revenue officer at Loews Hotels said: “I’ve always had the philosophy that OTAs are not the enemy. They’re a distribution channel that needs to be managed just like other distribution channels, like the GDS and anything that’s non-direct. We have a good relationship with the OTAs.”

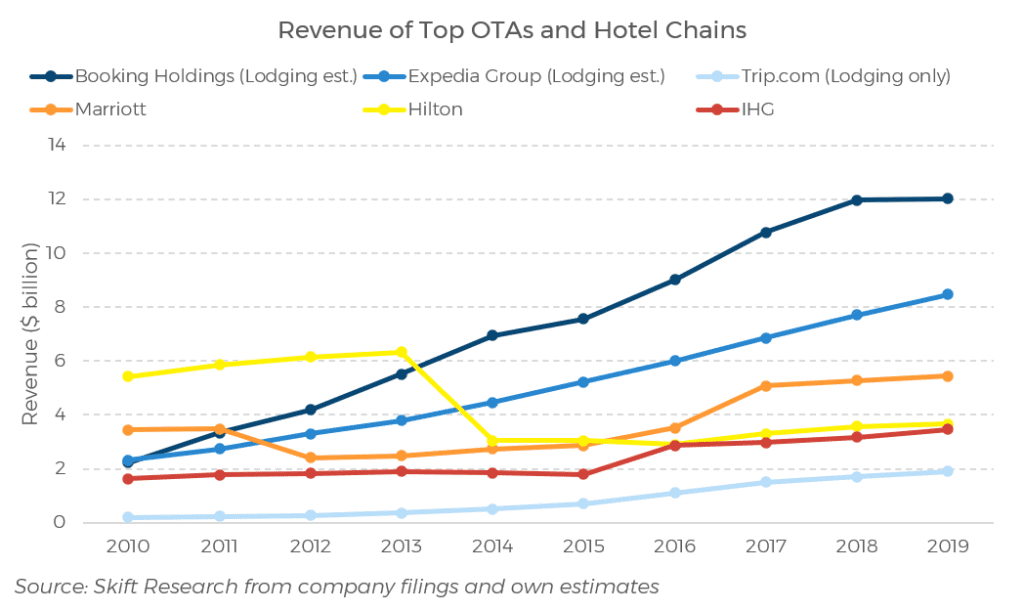

The largest players — and we should add Chinese Trip.com to the two Western players Booking Holdings and Expedia Group — have increased their sales and reach over the past decades, and their marketing budgets far outstrip even those of the largest hotel chains.

While OTA business models are vastly different from hotel business models — a commission based model versus a operator/management/franchise fee model — it is interesting to put the revenues collected by these players into context, so as to get a sense of the power play that is going on here.

Booking and Expedia have greatly outperformed the largest hotel chains, with lodging-only revenues of Booking Holdings estimated to be more than double that of the largest hotel chain Marriott. Expedia’s lodging revenues are higher than those of Hilton and IHG combined.

Skift Research estimates there are around 30 million hotel rooms worldwide. The three largest hotel companies by room count — as included in the exhibit above: Marriott, Hilton, and IHG — operate a combined 3.2 million rooms under their flags, which is still only 11% of total hotel inventory. This highlights how fragmented the hotel market is, but also how OTAs have been able to grow so rapidly. Smaller chains and independent hotels have a real need for OTAs to reach consumers they would not otherwise.

The increasing chasm between these big OTAs and the fragmented hotel industry does lead to concerns, which go beyond the level of commission.

Merchant vs agency model

According to our recent report about Trip.com, Booking Holdings’ total gross bookings were actually lower than the total gross bookings of Trip.com and Expedia, but its take rate is much higher. While Booking Holdings achieves a 16% take rate — in effect the average commission it achieves — Expedia sits lower at 11%, while Trip.com only achieves a 4% take rate. Especially Trip.com, but also Expedia, rely more heavily on lower margin sectors like air ticket sales, where commissions are largely negligible.

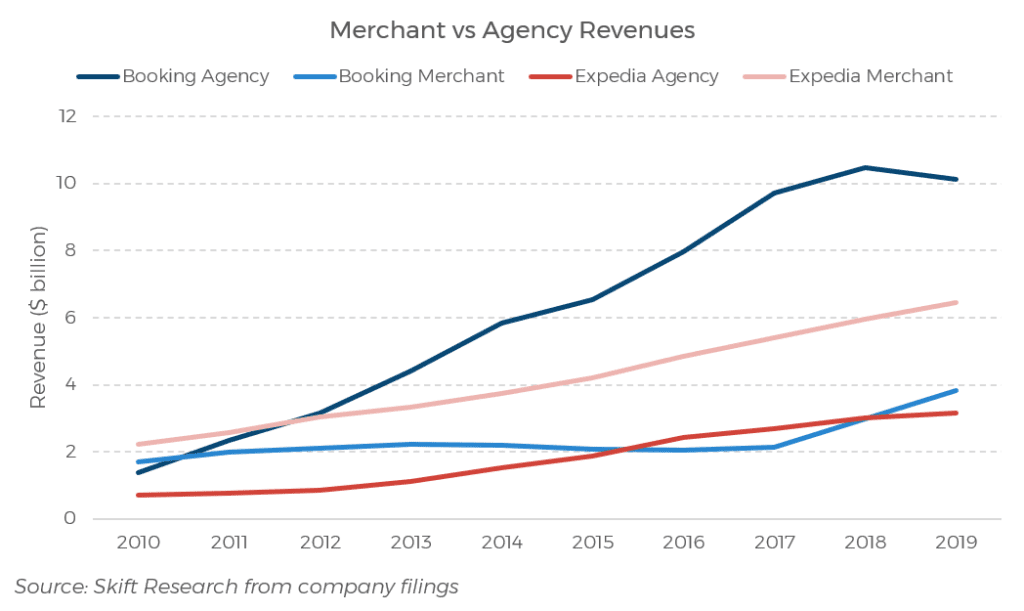

Another key difference is that Booking Holdings is predominantly operating under the agency model, while Expedia relies more on its merchant business.

The merchant model has historically seen hotels provide the OTA with a net rate, to which the OTA adds its margin before selling it. The modern merchant OTA approach is less about net rates and more about facilitating the payment process. Merchant OTAs enable flexible payment options in a centralized manner, providing value add to hoteliers that want to offload payment services.

Expedia generates almost 70% of its revenues (excl. marketing revenues) from the merchant model. Booking Holding’s Priceline and Agoda also operate largely using the merchant model. Booking Holdings has made an intentional shift towards merchant business over the past years, as it allows the company to roll out payment options like Alipay to all Chinese customers at once, rather than needing to convince each hotelier to sign up individually and find a payment provider which would support these alternative payment options.

This is where the agency model differentiates itself from the merchant model, in that consumers pay the hotel directly, and the hotel pays a commission to the OTA after the stay. The agency model has less costs and risks attached to it for the OTA, as the OTA is not the merchant of record and does not guarantee a certain level of rooms sold. As the consumer only pays once staying at the hotel, cancellation rates tend to be higher.

Booking.com is almost completely working with the agency model, and at its peak in 2017, more than 80% of Booking Holdings revenues (excl. marketing revenue) came through this model. Since then, the company has increased merchant business as explained above. Diversification into other segments like short-term rentals has also boosted merchant revenues.

The more traditional merchant OTAs that work with net rates, as well as opaque OTAs like Hotwire, which acquires rooms from hotels at discounted rates and sells to consumers who only have limited information about the exact hotel they will be staying in, provide hotels with lower risk business, or allow for last minute room sales without diluting its prices available on other channels.

For owners of branded properties, working with net rates can also be more attractive as it drives down their average daily room rate — because they report the net rate, rather than the gross rate paid by the consumer — and it therefore reduces the franchise fee they need to pay to head office.

The convergence of these different models, however, can result in issues around rate parity. Simply put, the problem with net rates — and we will go into this more below when discussing bed banks and wholesalers — is that the OTA can play with its commission. It can discount rooms by cutting its commission down from, say, 18% to 15% for a limited period. This reduces the price seen by consumers and leads to issues with rate parity, where the price on the hotel website or on other OTAs ends up being higher than on the OTA that applied the commission cut.

Keeping track of two or three large OTAs is not an insurmountable task for a hotel, but there are hundreds of smaller OTAs, many affiliated to the largest players to boost their inventory. This increases reach, but also makes the landscape more complex, and impossible to keep tabs on without tech to monitor rates.

To further complicate things, OTAs and other channels like flash deal websites, will request discounts to ensure they can offer the best rates to their consumers. We have heard reports that Expedia and Booking have been aggressive in their requests towards hoteliers to discount their rooms in response to the pandemic-induced demand slump.

While many countries have stopped OTAs from writing clauses in their contracts that force hotels to always offer the best available rates to the OTA, the larger OTAs will constantly scrape the internet to ensure that hoteliers do not offer their rooms at a lower rate somewhere else. While OTAs might not be able to put contractual pressures on hotels any longer, they can still apply other tactics like moving them down the search order if they find that hotels are not offering them the best available rates.

As one hotelier told us: “They fully understand that we have more competitive pricing on other sites than on theirs. And that’s why they push hotels to lower their rates on their platform as well. The more channels you use, each channel wants their specific advantage. Unfortunately, most of the time, in their eyes, the advantage is only based on price.”

OTAs’ marketing spend

It is, of course, within the OTAs’ right to make these demands from hoteliers. OTAs provide hotels with business they can’t necessarily get anywhere else, and they spend a lot of money to ensure this business is attained. As Christoph Hütter, a revenue strategy consultant, said: “what the OTAs really bring to the table … is a marketing force that nobody else can match today.”

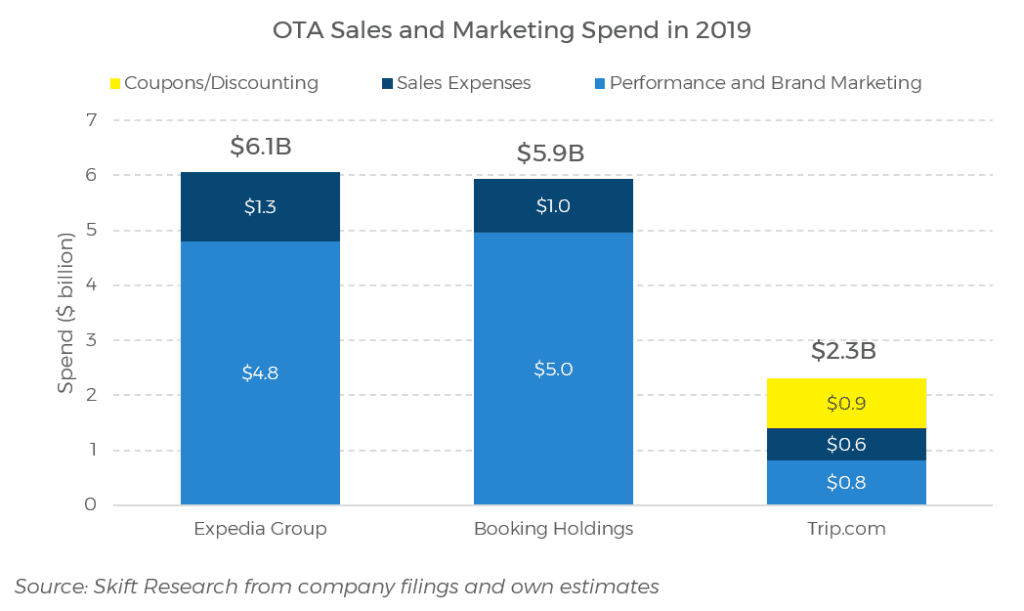

Arguably one of the most important indicators to track for OTAs is their marketing expense, as spending enough marketing dollars in the right place can make or break OTA profits. Booking Holdings and Expedia use a combination of brand advertising, metasearch, and online performance advertising campaigns to build a pipeline of shoppers at the top of the funnel. Both spent around $5 billion on performance and brand marketing in 2019.

On top of advertising spend, Trip.com also employs extensive promotional discounting and coupon campaigns. In our analysis of Trip.com, Skift Research estimated that the company spent around $900 million on coupons in 2019, which is a lever the company uses to lower prices to boost bookings. Taking this into account, Trip.com spent a total of around $2.3 billion on sales and marketing in 2019.

In comparison, during a business update call at the start of the coronavirus pandemic in March 2020, Arne Sorenson noted that Marriott, the largest hotel chain by far, spends around $1 billion annually on sales and marketing. A lot of this will be focused on its direct booking and loyalty campaigns.

We will discuss metasearch as a particularly important part of marketing expenses further below, but it is important to understand how this divide between OTA and hotel spending power leads to discontent amongst hoteliers.

One of the most important criticisms lodged at OTAs is that they compete directly with hotel advertising. Much is written about the billboard effect, where OTA shoppers will often still visit the hotel website before booking, offering hoteliers an opportunity to convert this looker into a direct booker. However, some doubt has been shone on the effectiveness of the billboard effect. This is why many hotels have started direct booking campaigns in the first place; to ensure that shoppers come to the hotel website directly without feeling the need to check an OTA first.

The problem is that OTAs are bidding on hotel names as part of their marketing strategy. As Christoph Hütter said: “Unfortunately a lot of trust has been broken where on various levels the business practices of some OTAs have not been balanced. Think about bidding on hotel brand names, I don’t think the OTA should do that. Of course they will because it’s extremely lucrative, and probably the best thing they can do after the destination hotel terms.” Monica Xuereb of Loews Hotels, and Shawn Jereb of Montage Hotels both mentioned that bidding on branded keywords by partners was a major headache, stating that they wrote specific keywords into their contracts with OTAs, to ensure they would not compete in this way.

Clearly, if the largest hotel chain only spends around a sixth of the major OTAs, smaller chains and independents have no way of outcompeting OTAs when it comes to marketing, especially when the spending power of these major OTAs is directed to consumers who search for your hotel name, and still see the OTA as the first option in the results list.

Metasearch

Let’s dive a little deeper into marketing, and especially metasearch. We have previously covered the role of the two largest metasearch players Google and Tripadvisor in deep dive reports, but here we will briefly look at the metasearch space through the particular lens of hotel distribution.

The rise of Google Hotel Ads

Google moved into the hotel metasearch space in 2010 when it started showing sponsored hotel prices in Google Maps. It has since predominantly worked with tech players to extend its efforts to most countries around the world and beyond Google Maps onto Google.com. In 2018 the company announced it was merging what was known as the Hotel Ads platform into the broader Google Ads platform, making it easier for smaller tech players and hoteliers to manage their ad spend and bidding.

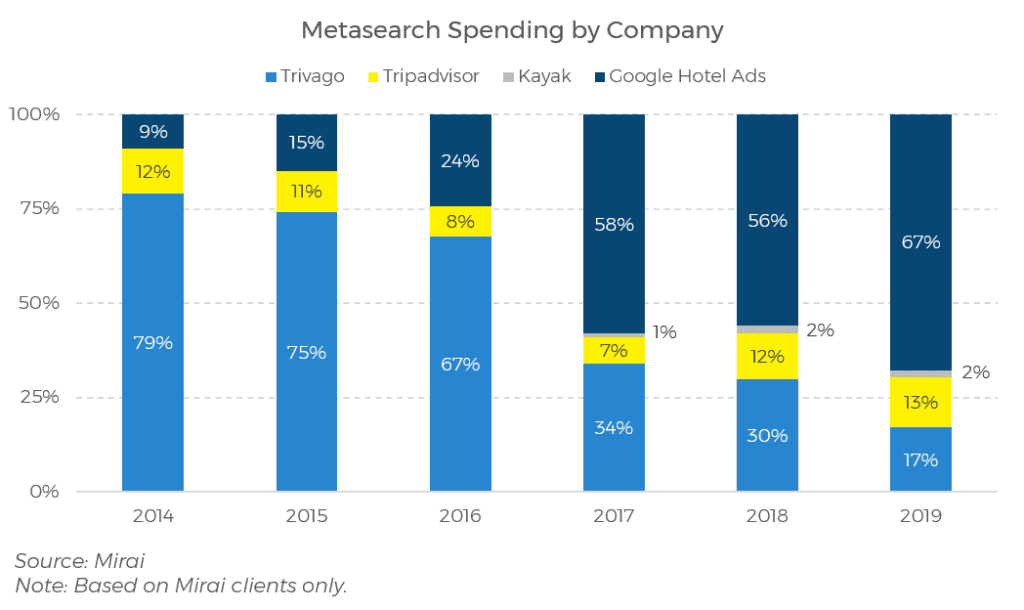

All these moves in the past 10 years have made Google the largest metasearch player. Analysis by online marketing agency Mirai showed that amongst its hotel clients, spending on Google accounted for 67% of all metasearch spending by 2019, up from 9% five years earlier.

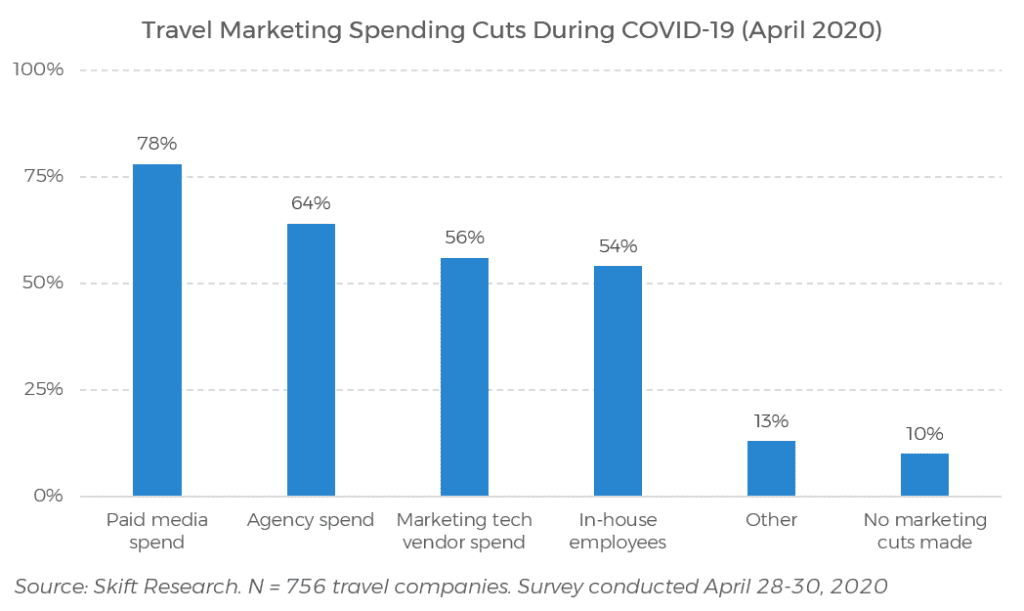

The pandemic has also hit metasearch, though. Skift Research found that nearly 90% of travel marketers slashed their marketing budgets because of the current pandemic. Google’s parent company Alphabet saw major declines in advertising revenue in March, with further declines during the second quarter. A survey conducted amongst 756 travel companies at the end of April found that paid media spending was hardest hit by the pandemic.

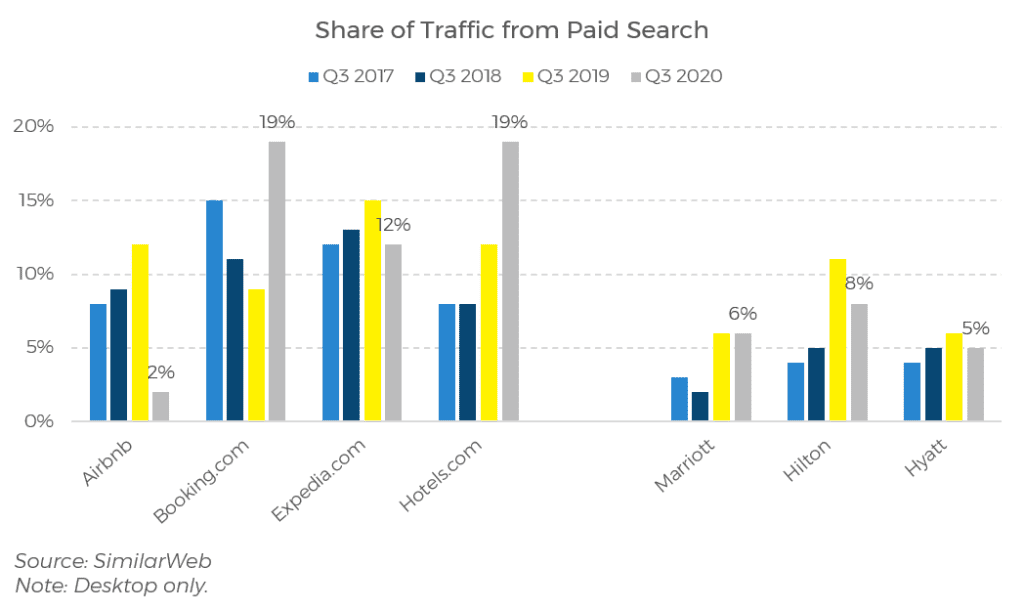

As demand has returned slowly during the second quarter, travel companies have responded differently to capture this demand. Some have seen their traffic through paid search drop strongly, like Airbnb which completely halted marketing spending during the pandemic. Others, including Booking.com and Hotels.com are trying to take advantage of cheap marketing.

A quick analysis of Trivago’s earnings shows how cost-per-click advertising has certainly weakened during the pandemic. Trivago reports revenue per qualified referral (RPQR), indicating how much the company earns per unique user that it refers out to an advertiser. We could use this as a proxy for a company-wide CPC. In Q3 2020, Trivago’s RPQR was €0.71, which was down 54% from €1,53 in Q3 2019.

This certainly shows that there remains some weakness in CPCs, and it might indicate that players like Booking.com and Hotels.com are just benefiting from less bidding competition, rather than spending more on paid search. It is interesting, however, to see the bifurcation between some players that continue to invest in metasearch as part of their strategy, while others have turned off the tap, at least for now.

Google has come in for some criticism, which can be expected when considering the dominance the company has achieved in just the last 10 years. Skift Founding Editor Dennis Schaal recently wrote that: “Regulators are flexing their triceps … [but] there is no reliable forecasting on how effective far-flung and elongated regulatory efforts will turn out to be.”

The European Commission is looking to enhance competition by preparing new directives that should curb the power of Google and other ‘gatekeepers.’ Meanwhile, in the U.S., a number of states and the Department of Justice have sued Google on antitrust grounds, in part focusing on complaints from competitors about the lack of a level playing field.

Ullrich Kastner of MyHotelShop explained the case competitors like Tripadvisor and Trivago are making against Google. “In the customer journey, Google Ads always comes before the metasearch, so basically Google can send free traffic into their own metasearch, while Trivago has to invest heavily in getting that same traffic from Google.”

At the moment, Google opening up Google Hotel Ads to more hotel players seems to be welcomed by hoteliers, who see it as an opportunity to boost direct bookings instead of relying on the major OTAs. Kastner, however, warns that Google “in two or three years might have a serious negative impact for hotels.”

This was echoed by Christoph Hütter, who referred to it as a possible “great awakening” after the pandemic is over. He said: “When Google blows up even further, who prevents them from charging similar commissions as what they do today in their app store, which is 30%. I am afraid that hoteliers will feel nostalgic to get their OTA commissions back in the not-very-far future, because they will realize that it was the far more profitable route.”

Google expands its click-per-stay model

Metasearch works with a number of different models. The most common model used is the CPC, or cost-per-click model, where hotels and OTAs bid a per-set amount on specified search terms. The bid amount, together with other factors like the room rate, will determine the ranking order on the results page. Hotels and OTAs only pay if the consumer actually clicks on their link.

The alternative is a CPA model, or cost-per-acquisition, which works the same as the CPC model, with the only difference being that the hotel or OTA only pays if a booking is made. All the major metasearch engines offer this alternative, with Trivago the last big player to start offering this model a few months ago.

Now, in response to high cancellation rates due to the pandemic, Google has made its commissionable model available to all Hotel Ads customers, beyond a small pilot group which had been running it for a few years. The commission-based model is also referred to as a commission-per-stay (CPS) model, where hoteliers and OTAs only pay Google after the stay has actually happened.

Tripadvisor introduced its Instant Booking product, based on the CPA model a few years back, but by all accounts has not been able to make it work. CPA is a much more complicated model than CPC, and a commissionable model even more so. The reason for this is the uncertainty that the metasearch engine has to account for in the bidding process.

CPA/CPS bids compete directly with CPC bids in the auction process, but since Google does not know how much they are going to earn from a click under the CPA/CPS model, they have to calculate with some uncertainty what each click is going to be worth. Not every click will be converted into a booking, and not every booking will result in an actual stay. This needs to be factored in by Google, in what becomes a very complicated algebraic exercise. Based on the outcome of the calculation, Google will enter the hotel’s bid into the auction, but won’t get paid for the resulting click until after the stay.

If anyone could pull the CPS model off it is Google, with its data and computing might. Hoteliers will be happy to see this option in turbulent times with high cancellation rates, which will further boost Google’s place in the distribution landscape.

Can anyone compete with Google?

OTAs have consolidated under the umbrellas of the two big companies of Booking Holdings and Expedia Group, hotel revenue managers are getting more aware of rate parity, and OTAs and bed banks are said to crack down harder on rate leakage. It therefore begs the question whether hotel metasearch as a product might become increasingly futile. Consumers will only use metasearch engines if they believe that there is a wide range of pricing options out there, as is currently the case with flights (many airlines fly similar routes at vastly different prices).

Google has the upper hand, as it marries metasearch with its search capabilities, therefore ensuring that metasearch is only an extension of its search capabilities. Other metasearch engines like Tripadvisor and Trivago, that rely on search traffic coming through Google (other search engines are available), will struggle as traffic is likely to dwindle.

This is why we have seen players like Tripadvisor pivot to offer a more ‘holistic’ customer experience, emphasizing reviews and experiences over hotel metasearch. Tripadvisor has also attempted to offer bookings directly on Tripadvisor, operating more like an OTA, which we similarly see Wego.com do in the Middle East. Rate parity clauses and regulations are on the way out, and in the longer term we believe that hotels will be better able to manage their parity — be it by relying on channel partners to police this or through technology like rate parity tools — putting a likely end to pure hotel metasearch players.

Bed Banks and GDSs

The bed bank business model explained

As with OTAs, there are some opposing viewpoints about the practices of bed banks and wholesalers. Interviewees agreed that bed banks could be part of a healthy distribution mix, as long as hoteliers do not over-rely on them for business.

The bed bank model works similar to the traditional merchant OTA model discussed above. The main difference between OTAs and bed banks — although it should be noted that lines are blurring rapidly — is that OTAs tend to focus on b2c distribution, while bed banks arrange b2b distribution. The similarity lies in the fact that both bed banks and merchant OTAs request net rates from hotels, which are generally about 20% below the best available rate that can be found on retail OTAs like Booking.com, and add their own margin and commission on top of that.

Bed banks aggregate demand from lots of different sources where OTAs don’t really play, and which, at least traditionally, were more expensive to reach. The major source is retail travel agencies, where the travel agent takes a typical commission of 10 to 15% of the booking value for each room booked through the bed bank.

GDSs work in a similar way to bed banks, but are used more often by corporate travel agencies and travel management companies (TMCs). With a long history in airline distribution, GDSs are also better placed to facilitate the distribution of flight tickets, while bed banks focus on the hotel stay. GDSs are moving into the hotel space as well, but hotels that use GDSs need a central reservation system (CRS) to connect to the main GDSs, which most smaller and independent hotels do not have.

Airlines and traditional tour operators also use bed banks to offer packaged options and a larger inventory to their customers. From his experience with working with major airlines, Tom Buckley, chief commercial officer and co-founder of marketing agency Wildebeest, noted that airlines that provide a packaged holiday option to its customers tend to self-contract with a few major hotel companies, and then backfill the rest of the inventory through a bed bank. Tour operators in a similar vein contract or own a select number of hotels, and then use bed banks for the remaining inventory.

Bed banks can also provide hotels with access to loyalty and credit card companies, as well as closed user groups like employee programs. In both cases, the credit card company or employer will offer discounted rates for hotel stays to its members or employees.

Finally, bed banks are increasingly connecting hotel suppliers to OTAs as well. This is something we are seeing GDSs do as well. Katja Bohnet, director of hotel distribution at Amadeus, for example, said that one of her company’s goals is to “penetrate further into retail and even leisure,” with the company increasingly connecting travel agencies and travel management companies to OTAs to achieve this.

There are a few major international bed banks, including Hotelbeds and WebBeds, and Expedia’s Travel Agent Affiliate Program could be classified as a bed bank as well. Major regional players include Travo, Bonotel, and HotelsPro. Trip.com also has a wholesale arm.

The issue of bed bank opacity

Bed banks are a great way to reach consumers that would otherwise be out of reach for hotels. This does mean, however, that they come at a price, which would generally be slightly higher than commissions paid to OTAs or for direct bookings. As we’ve already discussed before, OTAs take around a 15-20% commission on average, while bed banks would expect at least a 20% to 25% reduction off the best available rate.

Traditionally, bed banks would solely work with a static pricing strategy, where hotels provide a batch of rooms at a net rate to bed banks, but this is seen today as slightly outdated. Instead, many bed banks now also allow for dynamic pricing to emulate the retail OTA model. The key difference, however, is that the bed bank remains the merchant of record, and split its commission with the travel agent who sells the room to the customer.

The way a bed bank fits in the channel mix is explained by Xabier Zabala, global operations director at Hotelbeds: “Typically, the airline business, the packaged business, the retail agency business is longer lead times, so you build your base business from earlier on.” His colleague Paul Anthony, digital commercialisation director at Hotelbeds added that bed banks allow hotels to: “build their base and then keep adding. If you do it in that way, the revenue manager should be increasing rates, rather than decreasing rates when we get closer to arrival.”

A study by D-Edge on the European distribution landscape between 2014 and 2018 shows that Hotelbeds bookings had a lead time of 60 days. This time between when the booking is made and day of arrival is much higher than any other player, with Booking Holdings’ lead time around 35 days, and Expedia Group’s around 43.

Hotelbeds also argues that the average booking value is higher. Xabier Zabala said: “Typically the stays are longer, the spend of the travelers in the hotels is higher from this type of travelers, and the cancellation rates are approximately half.” Again, this is backed up by findings from the D-Edge study, which found that the average booking value for trips booked through Hotelbeds in 2018 was €422, compared to an average of €339 for Booking Holdings, and €342 for Expedia Group. Only direct website bookings were higher at €454.

Beyond the higher commissions, this sounds like a great channel for hoteliers to tap into. The problem is that hotels have very little visibility of where their rooms are being sold once they provide their inventory to Hotelbeds or one of the other bed banks.

Bed banks offer some options to hoteliers to decide which channels they can offer their rooms to, but this is a tickbox exercise of offering rooms to all channels, selected partners, or very selected partners. True transparency is never achieved.

Maybe more importantly, when bookings come in, hoteliers have very little insight into which channel attained the booking. Without that information, a hotelier might get all of its bookings from one particular travel agency or OTA, but WebBeds or Hotelbeds will always show up as the merchant of record. It is understandable that bed banks want to protect this information, so as to stop hotels from bypassing bed banks for more direct contact with a prolific seller of its rooms, but it does lead to discontent in the hotel industry.

As Simone Puorto explained: “Think about properties working with static rates, net rates. It’s very easy for a wholesaler or bed bank to undercut direct rates with net rates. And you never know, because you receive a reservation from channels you don’t have a contract with, so you have no idea where they are buying from. If something goes wrong, it is very hard to get to the source of the booking. With b2c it’s quite easy. If it’s a Booking.com reservation, it’s a Booking.com reservation, period.”

The undercutting of rates, as mentioned by Puorto is a persistent issue in the industry, and one that deserves a deeper dive.

Rate parity issues

The undercutting of rates, either by reducing commissions as pointed out before, or through other practices, all relate to the broader issue of rate parity and rate leakage. Reducing OTA commissions, as already discussed before, is one main culprit of rate leakage. Another is the reselling of rooms which were supposed to be part of a package. Here hotels might provide discounted inventory to a bed bank which is supposed to be sold by airlines or tour operators as part of a package. However, sometimes these rates find their way to other bed banks or wholesalers that might sell the room as a standalone product at the discounted price.

It is hard and futile to point the finger at one or another player. There are some bad apples, certainly, with now-bankrupt Amoma.com often mentioned as a particular culprit of undercutting rates, but it can also happen unbeknownst to the players involved. A wholesaler could receive rates from Hotelbeds and resell them to travel agents without problem. Consider that the wholesaler might now starts dealing with an OTA which sells directly to consumers, but continues to provide this OTA with the rates that were originally destined for travel agents only. The OTA uses different commission rates and rate leakage ensues.

Hotels are increasingly interested in tracking the parity of rates that are available on the internet. Chinmai Sharma, president of the Americas at RateGain said: “We’ve seen these parity violations on the rise again and some of our clients (both independent hotels and chains) have started to reach out for monitoring solutions.”

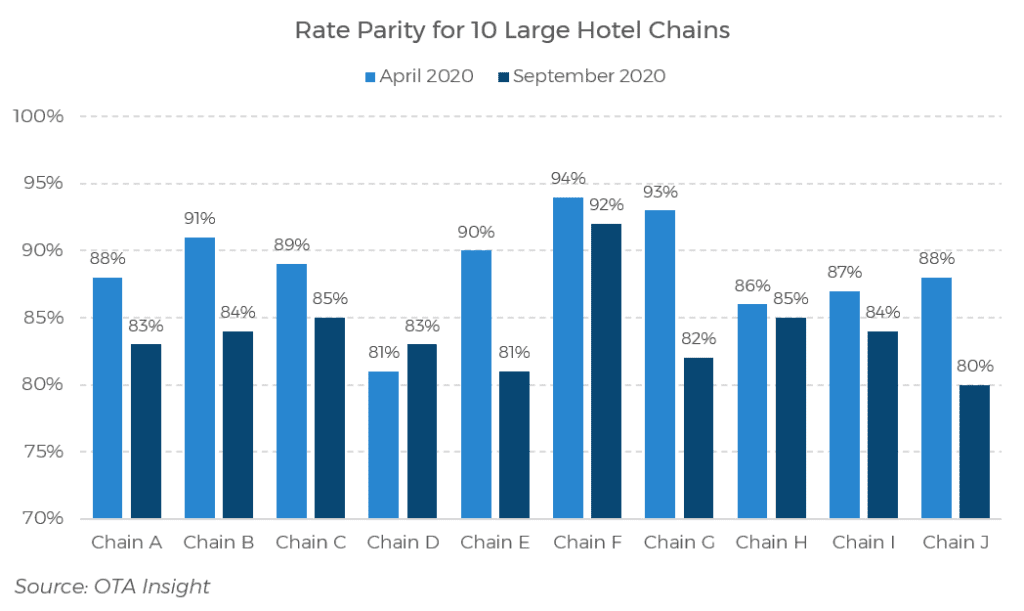

OTA Insight data backs up the idea that parity issues have been on the rise during the pandemic. Data shows that in an investigation of ten of the largest hotel chains, there were less parity issues in September compared to April for only one. OTA Insight captures this data by ‘shopping’ for hotels, and registering when rates on other channels are lower than on brand.com. A lower percentage in the exhibit below indicates more ‘shops’ that were not in parity.

Reasons for the increased disparity could be down to more rogue wholesalers, bed banks, or OTAs that undercut prices unbeknownst to hoteliers, but it is more likely that hotels are desperate to capture demand and are more eager to discount rooms on certain channels.

For hoteliers, complete rate parity is an ideal starting position to be in, as it allows them to provide discounts to certain channels or to direct bookers, in the certainty that they can promote those as the best value out there. However, there is not a single hotel in the world that relies for all its bookings on direct channels, so it is hard to see rate parity being ever fully achieved in today’s complex distribution landscape. Metasearch engines are actively advocating for rate parity clauses and regulations to be disbanded, as their entire business model is based upon different rates being available on different channels.

For hotels, having third-party players undercutting rates does not only result in loss of revenue, it also pushes hotels down the OTA rankings and has an impact on their marketing capabilities. Simone Puorto explained: “if you are doing a metasearch advertisement campaign and you have someone that is undercutting your rates, you will need to invest more money to advertise on metasearch, and the result will be worse anyway.”

Marriott recently entered into a relationship with Expedia, to ensure that wholesalers can only get net rates through Expedia Travel Agent Affiliate Program. This way, Expedia becomes the gatekeeper of all b2b rates that are available to resellers, and it greatly simplifies the process of checking rate parity and knowing who to hold accountable for Marriott.

Hotelbeds told Skift that they have also been busy to ensure rate parity is being policed better. The company has introduced a three-strike policy, where after three rate violations it cuts off its customers from access to its entire portfolio of b2b rates.

The complexity around hotel distribution, and the lack of transparency around bed banks, wholesalers, merchant and opaque OTAs, fuel the flames of talk about disruption in this space, and give oxygen to new ideas and startups to try and change things. Will the current pandemic offer the opportunity for new or existing players to bring true innovation and disruption?

The Future Channel Mix

The post-COVID channel mix will be similar to pre-COVID

In this report we have discussed the latest developments in the main parts of the hotel channel mix. Each channel has its own peculiarities.

Direct bookings are widely promoted as the best channel, but can easily become more expensive than a third-party alternative. OTAs have increased their power — at the chagrin of many hoteliers — by offering a good service, but sometimes also through less-than ethical practices.

Bed banks have built a vast network of travel buyers and suppliers that no one is even close to emulating, and while they lack transparency and may be operating with old business methods and technology, many hotels continue to rely on them as part of their channel mix.

The current pandemic has certainly changed how people book their stays, but it is doubtful that these changes will be permanent. At the moment hoteliers are less worried about curbing inventory to OTAs or bed banks, and many will be tempted to lower their rates. Rate parity is probably not a key issue for most. Non-refundable rates are no longer a thing, with travelers expecting to be able to cancel any stay last minute.

Booking windows have shrunk, with hoteliers telling us stories of on-the-day bookings skyrocketing, as travelers are not planning trips far out due to the pandemic uncertainties and they don’t need to worry about room availability. Chinmai Sharma of RateGain said his company is “recommending hotels to make sure that they are evaluating using niche last-minute channels like Hotwire and HotelTonight as they have the ability to bring in qualified and incremental demand.”

So while the channel mix is completely upended at the moment, there is no real sense in the industry that this will be permanent. There is a lot of talk about using the downturn to better optimize distribution practices, and while this is true up to a certain point, it is frankly impossible for hoteliers to make major changes to their distribution strategy now, in a time where they need all the demand they can get.

That’s not to say that hoteliers that have had too high a reliance on OTAs or bed banks, or hotels that want to attempt to get more direct bookings, shouldn’t start working now on a strategy that can be put in place once we hopefully move out of this crisis in 2021.

For now, more tactical actions like ensuring that information around health and safety standards is up to date on all OTA platforms should be the main priority. This might also be the right time to switch technology providers, keeping in mind, however, that a reduced staff base or staff returning from furlough will have their hands full on new operational practices and might not have a ton of time to learn new technology systems. We will discuss distribution tech more in part II.

Can COVID soften the hotel/OTA relationship?

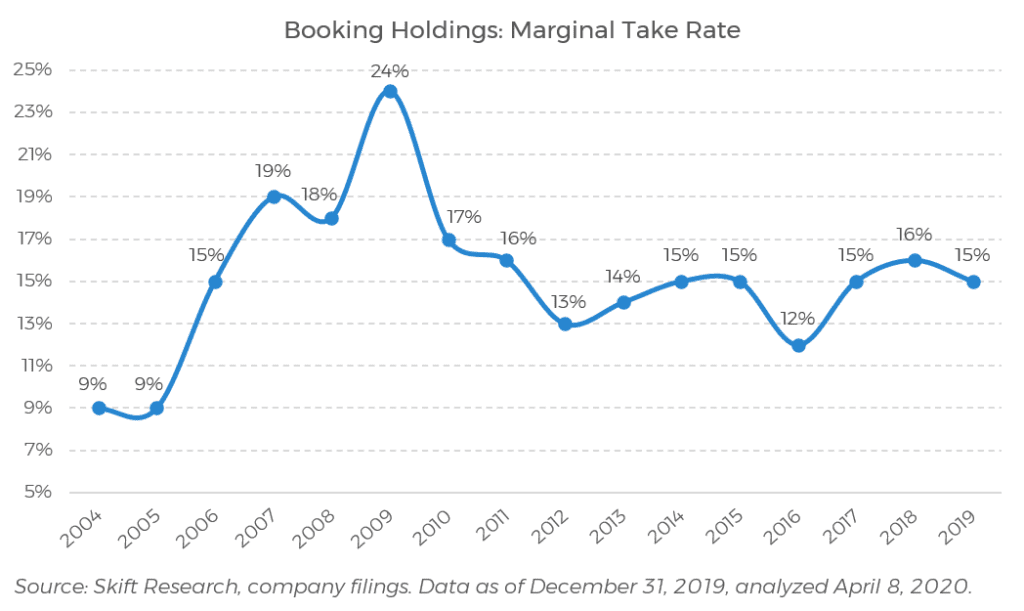

Skift Research analysis shows that the economic crisis in 2008/09 boosted the number of independent hotels joining the major OTA platforms, despite higher commission rates. Looking at the take rate of incremental bookings made through Booking.com in 2009 — i.e. bookings made beyond the level of the previous year — shows a major spike, indicating that many independent hotels joined the platform at a high commission rate.

Will this time be different?

Tom Corcoran, president and CEO at TCOR Hotel Partners doesn’t think so. Referring to a big drop off in business travelers and loyalty members, he said: “I think the OTAs are picking up momentum during this downturn, and they’re picking up more business because I think their apps are more user-friendly to the consumer. … The people traveling today are more used to using that, rather than our loyal brand customers.”

Craig Hewett, co-founder of metasearch engine Wego.com took a similar view: “People forget there’s going to be an economic impact in terms of people’s affordability. OTAs without a doubt provide the best source of deals and offers, and it is rich in choice. The gains these [hotel] suppliers made in direct bookings before COVID, I think it’s going to be shifted towards OTAs, and meta-search included.”

There was also little belief amongst our interviewees that the pandemic could see some new OTAs coming on the market which might take market share from the two big players.

Companies like MakeMyTrip in India and Despegar in South America are testament to the fact that regional players can disrupt the OTA duopoly, at least at a national or regional level. But in markets where Expedia and Booking are already established, it is tough for new OTAs to grow their inventory without becoming an affiliate of one of these OTAs, and to attract consumers with limited marketing budgets.

We are seeing some players trying to take a different route to success. Stay Bonanza and Bidroom, for example, are offering commission-free hotel distribution. Instead of charging the hotel a commission, these OTAs charge travelers a small membership fee. And with no commission fee, they expect to receive prices that are below the best available rate offered to other OTAs.

It’s a great idea on paper, but as Evan Davies, founder of Channex.io said it bluntly: “It’s so tough for these OTAs. If they are commission free, they don’t make any money. So they can’t go on Google and bid. So they just get no traffic, which means no bookings, which means you’re out of business.”

Focusing on a membership fee sounds like a good alternative to get much needed income, but it is extremely hard to attract a large number of customers willing to pay a membership fee for an unproven service, and a business model based on an annual member fee is much harder to scale than a commission-per-booking model.

Maybe, instead of expecting disruption to come from other OTAs, hoteliers need to hope that the common struggle that the pandemic delivered will have a long-term impact on the hotel/OTA relationship. Steve Lowy, CEO and founder of The Residence Apartments, believes so. “I think this whole crisis may have toned them [OTAs] down a bit in terms of: we’re part of the mix, we do actually need to work together, and we’re no good without each other.”

Until there is evidence that supports that sentiment, hotels need to have a clear idea of their OTA strategy, understanding how much availability they want to share with OTAs, and how open they are to discounting to get better placement on these platforms. Don’t expect that the current pandemic will change anything fundamentally in this space.

The uphill battle to disrupt bed banks

Bed banks and GDSs have also been impacted considerably by the pandemic. With GDSs relying heavily on business travel, which has come almost completely to a halt, and bed banks relying predominantly on international leisure travel, which has been impacted severely by border closures, both channels have seen volumes plummet.

Monica Xuereb said that Loews Hotels had seen GDS bookings decline from around 20% of the channel mix in normal times, to about 3% today. Mike Ford, managing director at channel management vendor SiteMinder similarly noted that GDS sales coming through its software had halved from about 10% normally to around 5% today.

Bed banks are similarly in a precarious situation, as they have built a large tech stack and employ a large workforce of sales representatives to keep growing the number of suppliers and agents that use the system. “They rely on net rates to have a margin, so the more volume they are doing, the more margin they can get. With less volume it becomes much more challenging to support the costs of the team and technology,” said Pierre-Charles Grob of D-Edge.

So while these players are on their knees, is there an opportunity for other players to disrupt this space?

Hyperguest is a marketplace which is trying to disrupt the incumbents by offering accommodation providers and travel agencies the technology to connect directly, without the need of a bed bank or GDS to intermediate.

Enzo Aita, global head of business development at the startup, explained what is different about Hyperguest’s business model. “With Hyperguest, [hotels] have no pre-contracted commitment, and they can set up their own preferences. Hotels switch channels on or off, not an entire basket but a single travel provider. Hotels decide terms and conditions, and the travel provider has to accept these terms and conditions. The hotels decide the commission they want to pay, and the travel agent signs up to accept it. It’s really reversing the approach.”

The key issue for a young startup is of course to get enough suppliers and travel agents to use its technology to start disrupting the status quo. Hotels might be willing to give this a try, likely interested to hear that they can set commission rates, rather than being guided by their channel partners. But convincing travel agents might be harder, as they have entrenched ways of working, and established contacts and contracts.

Other startups that know all too well the pain of trying to break through entrenched business practices are blockchain startups Winding Tree and Arise.

CEO and co-founder of Arise Nadim El Manawy said in previous conversations with Skift Research: “Our technology can bring way more transparency, trust and control back to the hoteliers. … Over time we are looking to replace the GDSs and the wholesalers, both which have different users, but both are a black box running on old tech.”

Arise and Winding Tree, however, have struggled to get inventory on their alternative channels, and to get travel agents interested in using their systems. Proponents posit that blockchain can revolutionize hotel and airline distribution, offering more transparency and flexibility, cutting out middlemen and lowering commissions. So far it has failed to live up to its promise.

Admittedly, blockchain technology could bring some disruption. One area that shows some potential, but stops short of truly disrupting the current distribution channels, is in making negotiated rate commissions more transparent. Smart Hotel Rate is one company working on this, and we understand that Arise, the aforementioned blockchain startup, has also pivoted in this direction.

Johnny Thorsen, vice president strategy and innovation at American Express Digital Labs, and an advisor to Smart Hotel Rate, said of the potential of this technology: “The buyer and the hotel always look at the same, real-time data, instead of completely disconnected systems where they have to spend hours in Excel trying to figure out how much did you buy from me and how much did you pay me.” This may be a starting point for blockchain to become part of the distribution landscape, before ultimately infiltrating into other layers of the channel mix, but the latter would be a long term prospect.

So how about other existing players that already have the contacts, but aren’t currently playing in the wholesale space?

Channel managers are tech vendors that might be able to provide a similar service to bed banks. Channel managers are key tech providers in the distribution space, where they are the connectivity providers between hotels and all other channels. If for argument’s sake we forget for a second that channel managers currently work with bed banks and wholesalers, we could see them as a possible disruptor.

SiteMinder, the largest channel manager, already has established connections into the hotel tech stack of ~35,000 hotels, which at face value is less than the 180,000 hotels that Hotelbeds has contracts with, but it is a much deeper relationship where SiteMinder has oversight of bookings made through all third-party channels. They also have what is likely the most complete set of connections with OTAs and wholesalers of any player in the hotel distribution space.

Mike Ford of SiteMinder agreed that on the face of it, it looked like a potential opportunity, but he pointed at the long standing relationships that bed banks have built with travel agencies and hotels over many years, which are hard to emulate without a considerable investment.

Additionally, Ford said the role of channel management, as a neutral connectivity platform, inherently differed to that of bed banks, which have created value from influencing supply and demand. “It’s not simply a matter of offering it out and everyone will come. There are points of sale that they’ve developed and contracted. It’s a vastly different type of intermediated space,” he said.

While this may be true, it is likely that bed banks will have been forced by this pandemic to become leaner, with more focus on improving their tech stack and reducing their on-the-ground sales force.

This is a process that was already put in motion by many bed banks, and will likely only accelerate. Hotelbeds, for example, introduced its MaxiRoom extranet back in 2015, which works very similar to OTA extranets, where hoteliers can update their availability and rates. Paul Anthony of Hotelbeds said that the company needs to look beyond the basics of rates and availability, and instead at “how [hoteliers] can start creating new rates and new availability in a seamless way that comes into us and we then distribute out, … making the end-to-end process as seamless as possible.”

In this way, bed banks are trying to emulate how hoteliers interact with OTAs. It is one further way that lines between different players in the channel mix are blurring.

In contrast, OTAs are also increasingly looking more like bed banks, with Expedia Partner Solutions, Booking Holdings’ Agoda, and Trip.com all offering rates to b2b partners. In that sense, the biggest threat to bed banks might actually come from OTAs, which is not necessarily the kind of disruption hoteliers are waiting for.

Conclusion

Hotel distribution is a complex process. In a market where demand fluctuates strongly, and a myriad network of channels compete for sales of the same room inventory, hotels need to understand how the different channels operate and have a clear strategy in place to allow for the best possible distribution of their rooms.

At the end, for hoteliers it all comes down to proper management. There is a reason the different channels exist, and at present no one is in a position to do a better job than the incumbents. That is not to say that disruption will not come eventually.

Evan Davies of Channex.io mentioned voice assistants as a potential disruptor, and there is merit to this argument. If booking hotels through voice assistants becomes mainstream, Google and Amazon have a clear upper hand at the top of the funnel. Will they work with partners to display hotels on a screen or provide spoken recommendations? Or will they go at it alone? While this would be extremely disruptive, it might simply replace one duopoly with another. It certainly gives the industry something to think about.